Readers on Substack often lament that they are unable to find new newsletters, and indeed, the platform will need to improve discoverability as it grows. Until that day, perhaps I can do my part by suggesting a few newsletters to you, my dear readers.

And so, here are 5 newsletters I think you should read. Consider subscribing to them and, if you haven’t already, consider subscribing to Commonplace Philosophy to help support my work as well.

Woman of Letters

does not need more hype right now. After being featured in The New Yorker for a novella she published on Substack, she’s getting quite a bit of attention, all deserved. Yet, I think people might still be overlooking how consistently interesting Naomi’s writing is. She publishes both essays and fiction, and these tend to intersect in terms of focus. For instance, she just published a short story on the decline of literacy:

I’m someone who has written extensively about the decline in literacy. My videos about the decline in literacy and atrophying attention spans have earned millions of views on YouTube, and my essays on the subject tend to do well. And I have to admit that I’m growing tired of it all. I’ve said what I can about it, and I don’t know if there’s much else to say. With each new piece about the literacy crisis, I feel we’re running the issue into the ground. (The same could be said about AI; more on that in a later post.) Naomi’s story, in contrast, feels fresh. It’s a parable, as one commenter noted, making us feel something, pointing us toward some truth, but Naomi leaves articulating that truth as an exercise for the reader.

Naomi has consciously shifted her style, writing more in the mode of an epic. She writes about the story and has moved away from small details. I personally enjoy this mode of writing immensely, and I’m glad she’s doing it.

Want to be a bit more like Naomi? Well, it turns out she’s revealed the secret to her success: reading the Mahabharata.

Bentham’s Bulldog

I was originally going to describe Bentham’s Bulldog as ‘often wrong, always interesting.’ While I do think he is often wrong, I don’t think this is the best way to lead here, especially since I’ve never bothered to argue directly against him. Let’s focus on the always interesting part.

BB made a name for himself when he started vigorously defending shrimp welfare. BB’s arguments tend to follow a pattern: he’s a utilitarian and effective altruist, and he’s willing to go where his premises take him. Thus, in a recent post, he argued that insect suffering is the biggest issue in the world.

BB’s views tend to attract quite a bit of hate, including people who simply want to insult him. In my view, his haters are typically revealing that they don’t have good counterarguments. Very often, it follows this sort of pattern:

BB points out that some phenomenon, X, amounts to mass suffering and thus should be obviated or eliminated in some way. He’ll propose a plan, call it A.

The haters point out that this presumes consequentialism is true and, since it isn’t, they aren’t obligated to follow A.

BB will argue that even if one is not a consequentialist, mass suffering is morally relevant, so A or something like it is still morally required.

The haters point out that nobody agrees with him, and also that he is a weirdo.

Nowhere in that argument is the crucial point - that mass suffering is morally relevant and should be obviated – contested, though it is seemingly rejected. This is a strange fact, given that nearly everyone thinks that unnecessary suffering is bad. Yet, when BB uses it as a crucial premise in an argument, people tend to reject it without thinking of how strange this is.

It may be because he is, frankly, a bit of a troll. It makes his writing fun, but it makes the haters angry. Yet, his strategy is surprisingly effective. The Daily Show ran a segment on shrimp welfare recently, and given the buzz around BB’s piece, I assume he played some role in bringing it to some writer’s attention.

He isn’t only a utilitarian, though. He’s also quite interested in the philosophy of religion, and he seems to lean toward theism. It’s an interesting pairing that one rarely sees out in the wild.

Other pieces worth reading:

Tariffs are Evil, Not Just Bad Economics, in which he argues on moral grounds against an economic policy in the news.

Why I’m Not A Christian, in which he argues against Christianity despite his shift toward theism.

A Ruthless and Merciless Ranking of the Ten Best Blogs, in which he does not mention me a single time.

The Metropolitan Review

Readers on Substack sometimes complain about the platform’s monetization strategy. When they make these complaints, I think they are expressing a desire for a return of the magazine model — a model in which a few editors curate writers and articles of interest, offering it all for a reasonably low monthly price. I’m not sure how viable this model is on Substack or on the internet today, but The Metropolitan Review is giving it an honest try.

Without a doubt, the best piece published by The Metropolitan Review is this profile of the writer William T. Vollmann. In this profile,

(author of Cubafruit, a novel I’ve recommended before) details the frankly insane journey Vollmann’s most recent novel, A Table for Fortune, has taken. As Sorondo begins the piece:A few years ago, the novelist William T. Vollmann was diagnosed with colon cancer. The prognosis wasn’t great but he went ahead with the treatment. A length of intestine drawn out and snipped. It was awful but it worked. The cancer went into remission.

Then his daughter died.

Then he got dropped by his publisher.

Then he got hit by a car.

Then he got a pulmonary embolism.

But things are looking up.

Vollmann is now, seemingly, about to publish A Table for Fortune. It is 3,400 pages, will be published by Arcade (a fairly small imprint of Skyhorse), and might be his masterpiece.

This is just one sample of the sort of stories and pieces The Metropolitan Review runs. Consistently interesting, discourse-generating (in the non-perjorative sense), and, quite possibly, a sign of things to come as the media ecosystem continues to evolve.

In addition to reviews, profiles, and essays, however, The Metropolitan Review runs fiction pieces. Here are two worth reading:

An excerpt from

’s Metallic Realms

Fake Nous

I recall first reading

in a graduate seminar in epistemology: we read Skepticism and the Veil of Perception. I remember enjoying it, though I’ve forgotten nearly all of the details. Then, years later, I read his excellent The Problem of Political Authority. That is a book that has stuck with me. As someone with significant anarchist sympathies, I tend to think that the problem of political authority is one of the great issues that we all ignore because we don’t know what to do if it can’t be solve. (I think this is also true of external world skepticism.)If I had to characterize Huemer’s philosophical style, I would put it like this: Huemer enjoys finding simple arguments for extreme conclusions. For instance, he believes that existence is evidence of immortality, and he can summarize that argument in a paragraph:

Claim: Every person has been incarnated infinitely many times in the past, and will be reincarnated (live another lifetime) infinitely many times in the future.

Summary argument: Time is infinite in both the past and the future directions. Given infinite time, whatever conditions (including disjunctive and conjunctive conditions) caused you to be born will repeat, to any desired degree of approximation, infinitely many times. A sufficiently close approximation to the conditions that brought about you (i.e., your current incarnation) will count as literally bringing you to life again. There are some theories of persons that would reject this, but these theories also imply that your present existence has probability zero. Since you are presently here, those theories are wrong.

The rest of this post gives the argument in some more detail. Huemer is doing something I wish more professional philosophers would do: taking his published articles and repackaging them into posts on Substack, making it easier for people to engage with the arguments.

Notebook

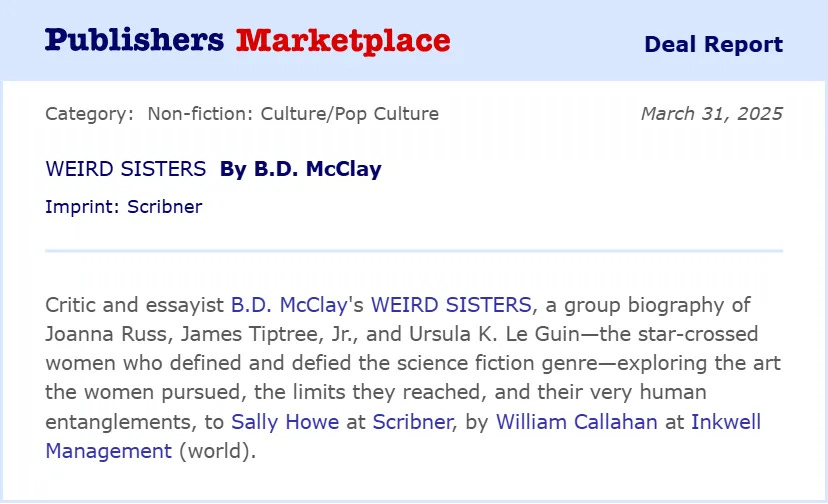

writes Notebook, something of a hodge-podge of reviews, essays, and monthly ghost stories. I had read her writing before coming to Substack; I believe the first time I found her was via her article on Joanna Russ. She’s also written on a personal favorite of mine, Ursula K. Le Guin. And now you can read her ghost stories and (even more unexpectedly) her reviews of Neon Genesis Evangelion on Substack.BDM also deserves a mention because she is writing a book I am very much looking forward to: a group biography of Russ, Le Guin, and James Tiptree, Jr. As a lover of that era of science fiction, I’ll be eagerly awaiting preorders for this book.

I could go on, but Substack’s UI is telling me I am dangerously close to the email length limit.

I should not have read Kanakia. Thanks to her, I have that 10-volume Mahabharata arriving my house any day now.

Jared, I should not be bothered to do so. As is my right and preference. But, I will do what I must!