Welcome back to our read-along of Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition. We’re over halfway done with the book, and we’ll be finishing it this month. The rest of our schedule is here:

January 6: Chapter 5: Action (§24-29)

January 9: Members-Only Zoom Call (3PM Eastern)

January 13: Chapter 5: Action (§30-34)

January 19: Members-Only Zoom Call (8PM Eastern)

January 20: Chapter 6 The Vita Activa and The Modern Age (§35-40)

January 27: Chapter 6 The Vita Activa and The Modern Age (§41-45)

February 3: Final Thoughts

Note that we have two members-only calls in January. The first is January 9, at 3PM Eastern, which I hope is more friendly for those in European timezones. The second is January 19, at 8PM Eastern, which I think is convenient for those in most Asian and North American timezones.

To join those calls, become a paying subscriber. We’ve seen a small surge in subscriptions lately, which has been tremendously helpful for me and for which I am grateful; it also means we can have more robust discussions going forward.

One more note: our next book is Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. This book is terrific, and one I’m very excited to read with you. In the post announcing the 2024 read-alongs, I said we’d start it in March. I think that’s right, but we might start the last week of February. I’ll have the schedule finalized soon — but I’m letting you know now so that you can go ahead and buy a copy.

It has been some time since we started reading The Human Condition, and so far our discussion has focused on labor and work, so it is helpful to remember that Arendt begins the book with a three-fold distinction between labor, work, and action.

The Stanford Encyclopedia article on Arendt describes the distinction this way:

Labor is the activity which is tied to the human condition of life, work the activity which is tied to the condition of worldliness, and action the activity tied to the condition of plurality.

This description, like Arendt’s original text, is frustrating — something I’ll admit now that we are this far along. On occasion I find myself excited when reading The Human Condition, and for a few different reasons. I’m also skeptical of a technocratic, laboring society; I am interested in the philosophy of work, and while I don’t love the labor/work distinction, I do think there is something in the vicinity worth including in a substantive analysis; Arendt occasionally include an observation about our present world that I find striking. But it is hard for me to see the larger thrust of the book, to see exactly where we are going. On top of that, it is difficult for me to see where any particular human activity will fit with the labor/work/action distinction. We’ve talked a bit about the problems with the labor/work distinction, but now we’ll move on to action.

“Action, the only activity that goes on directly between men without the intermediary of things or matter, corresponds to the human condition of plurality, to the fact that men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world,” Arendt says back in Chapter 1. Activity without intermediary things, then, might be the characteristic feature of action — it is defined, then, by a lack. But when we get to chapter 5, that doesn’t seem to be emphasized nearly as much.

Why do we need action, activity without an intermediary? I think that the answer is that action (along with speech) uniquely discloses our identity to others. This is Arendt’s theme in Chapter 5. Action tells people who we are in a way that labor and work do not. In fact, Arendt goes on to say that if action is not disclosing an agent, then it loses its specific character:

Without the disclosure of the agent in the act, action loses its specific character and becomes one form of achievement among others. It is then indeed no less a means to an end than making it a means to produce an object. This happens whenever human togetherness is lost.

With this understanding of action, we might be able to make sense of earlier claims about Greek philosophy – always Arendt’s reference point – that in the public realm one is able to be an individual; this would have to be because the public realm allows for disclosure through action.

“The organization of the polis,” Arendt says, “is a kind of organized remembrance.” This is an interesting point, and one that I think we should consider more. The walls of the city, its law-given organization — all of this contributes to a stability that allows for ‘organized remembrance,’ thus giving a life to the fleeting acts of greatness beyond our individual recollection.

I was reminded here of a typical Orthodox practice, in which a parish community says memorial prayers for the departed around the anniversary of their death. In some communities, this can continue for an awful long time — at my own parish, I’ve taken part in memorial prayers for people I’ve never met. We conclude those prayers with a hymn: “May his memory be eternal.” This has a peculiar theological significance, but it also has a human resonance; it tells us to do our best not to forget those who built this community and have gone before us. A little organized remembrance.

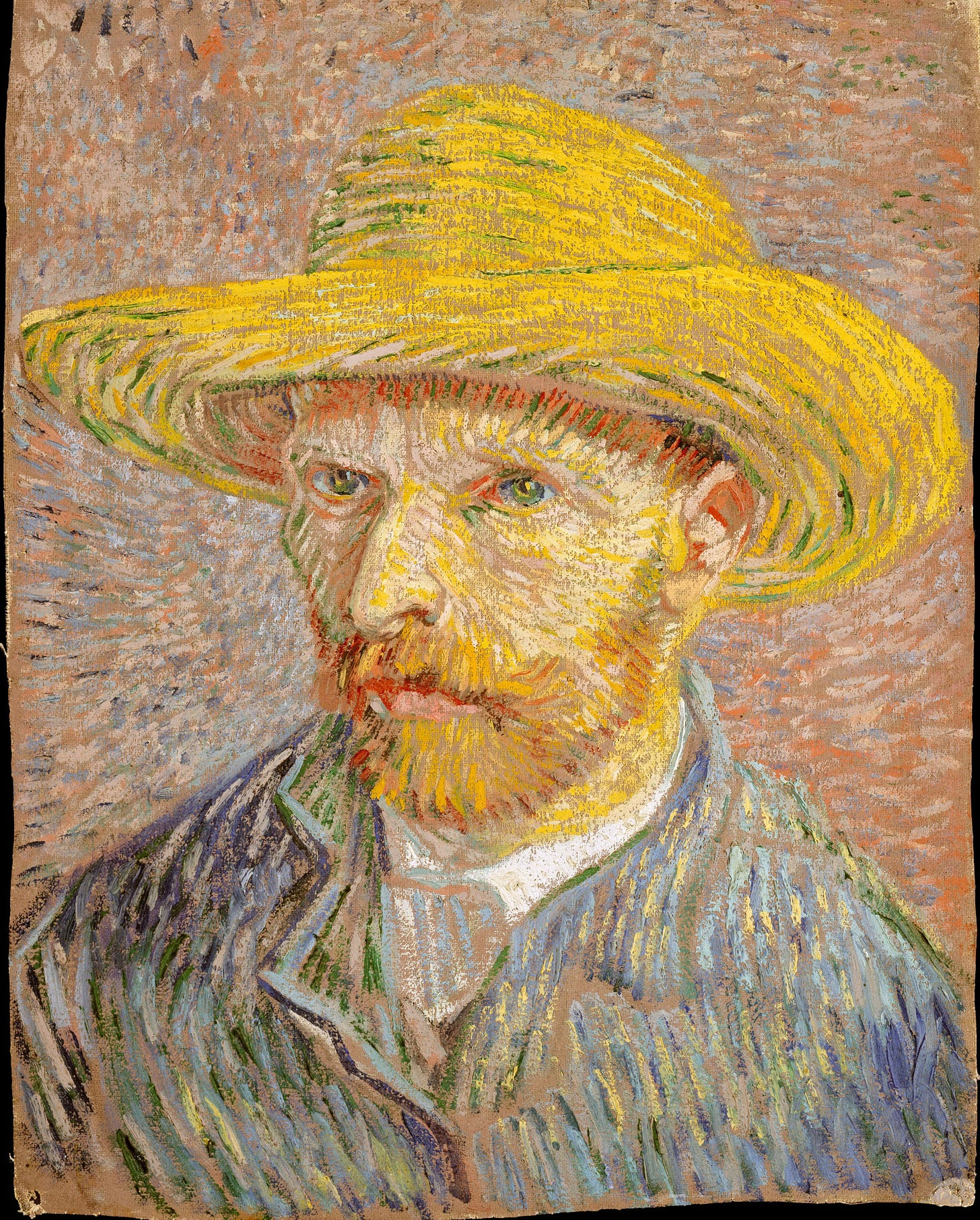

This point about the polis was a high point in the first half of the chapter. I was troubled, however, when Arendt spoke of art being an imperfect medium for disclosure of an agent. Art is work, recall, in part because it produces an object. Art is not action. ‘An art work retains its relevance whether or not we know the master’s name,’ Arendt says near the end of §24, while actions seem to be relevant only when we know who commits them; thus, we’re supposed to reason, action uniquely discloses an agent to others. (I fail to see the force of this point, so either Arendt is completely wrong here, or I have missed something important). It seems to me that great art does in fact tell us something important about the agent, perhaps indirectly.

What say you?

I'm not sure if I understand what she means by action only being relevant if we know the actor either, but my best guess would be this:

A piece of art can tell us something about the artist, but the artist isn't strictly necessary (even though knowledge of them can enhance our relationship to their work). We can look at sculptures from ancient Greece without knowing who made them and still appreciate them.

But we can't effectively tell the story about how an anonymous person rallied an anonymous group of people to go to war against another anonymous group of people. We need to know who the actors in the Trojan War are, in order to have an appreciation for this "action"

I don't take Arendt's point about actions disclosing our identity to mean that work can't also disclose some aspect of our identify, merely that it cannot do so as deeply nor profoundly as action. She definitely seems to be attributing a special kind of disclosure of identity to action, but I didn't read that as precluding any other way of disclosing at least some aspect of identity.

I primarily took this point as a modified version of "actions speak louder than words," in that one is only reliably revealed to the world through action. Action, in this way, is less prone to misrepresentation, deception, or misinterpretation than any disclosure through labor or work. I don't know if I fully agree here, but I think the point has some merit.

However, I am definitely struggling to get a firm grip on her concept of what constitutes "action" in terms of normal human activities.