As we work our way through a book – any book of nonfiction that has an argument or thesis, at least – we try to identify positions that the author takes. Sometimes the author is helpful, adding clauses like ‘The main argument of this book is…’ or ‘Thus,…’ to tip us off to that the embedded proposition is one that the author actually believes. This answers the what question: What does the author believe?

But there is a further question, one which presumes an answer to the question above. This is the why question: Why does the author believe it? When we ask the why question, we’ve moved on from merely reporting facts about a book to the act of critical assessment.

This probably sounds like basic stuff — of course we want to know why an author believes whatever it is that the author argues. But when I taught undergraduates, I found that moving from the what to the why was a real obstacle. I suspect that there are a few reasons for this.

First, the why question is difficult to answer. In order to answer it, you probably need to know something about how arguments are structured. You should know about logical structure (or at least have an intuitive sense of it); you might want to know a bit about fallacies; you need to know the difference between deductive, inductive, and abductive arguments. Above all, you need to know that most writers are actively trying to hoodwink you, and that as a critical reader you need to make sure they do not succeed. Since this is all quite a bit of work, students opted out. As an instructor, I had to coax them into it.

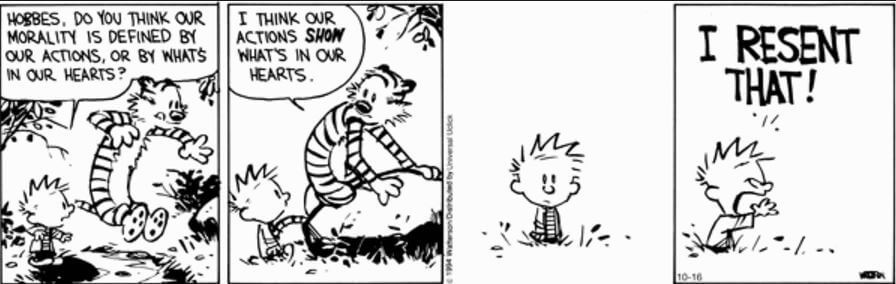

The second reason is that many of us have a sense that disagreement is rude. We don’t want to offend – unless we’ve decided that our opponent is someone who really deserves to be insulted – and we worry that disputes about facts and evidence will be interpreted as insult. This is endemic. Students would often hedge what they said in class with phrases like ‘I’m not disagreeing, but…’ while going on to voice what would clearly be a contradictory point, or perhaps say that they were ‘following up’ on a point when in fact they were trying to refute it.

I’ve been thinking about this second reason quite a bit lately, and I wanted to share some quick thoughts.

Disagreement is a sign of respect. That point might sound odd – after all, we associate respect with deference and politeness – but I think that the argument for this is pretty straightforward. When you and I are engaged in a debate, I can adopt one of three attitudes:

We are epistemic peers. We are roughly equally rational, sensitive to evidence, and open to persuasion.

I am your epistemic better. I am more rational, sensitive to evidence, or open to persuasion.

I am your epistemic lesser. You are more rational, sensitive to evidence, or open to persuasion.

(This is a bit of an oversimplification.)

Now suppose that you and I disagree about something. When I decide to followup on this disagreement by arguing with you, I am adopting the first stance. I am treating you as a peer who can be reasoned with. I am assuming, and acting on the assumption, that you and I are the sorts of people who can have meaningful debates — perhaps even one where we change our minds.

If I chose not to followup on a disagreement, and instead decided to just chalk it all up as a matter of opinion, I’m often adopting the second stance. I am assuming that I’m better than you. You aren’t the kind of person that should be reasoned with — maybe you’re type of person who can’t be reasoned with. Sometimes, I adopt the third stance, in which case all of the insulting things are being assumed about myself. So, by disagreeing and following up on it rationally, I am showing that I respect you and that I respect myself.

Now, how we voice disagreement is key here. Sometimes it can get rather sharp, and even the well-intentioned can cross a line — but that just shows that disagreeing well is a skill that we have to develop. And we do not develop it if we refuse to have arguments in the first place.

Interested to develop this skill. I’ve got an itch to get into meaningful discussions with people and I opt out sometimes out of not knowing how to take the next step. Occasionally I’ll find something they said to latch onto to carry the conversation forward, but it’s few and far between. Sometimes I think (perhaps wrongly) that people aren’t that interested, that I’m trying to consider something too deeply, or it’s also possible that I’m just not operating in good faith and don’t extend care to the other in the conversation. Finding the right next question to ask is difficult.