Gatekeeping Ourselves

Why students don't want to read, saving reading culture, and being our own worst troll.

This morning’s essay is a bonus, available to free and paid subscribers alike.. I’ve been thinking a good deal about reading, about reading culture, and about the stories we people who love stories tell ourselves.

Last Sunday, as part of The Weekly Reading List, I shared a pair of articles on the decline of reading. First, an article from the Chronicle of Higher Education. Second, an essay on Substack from Miller’s Book Review. Both note that there is a genuine decline in desire and ability to read among younger students.

In Beth McMurtrie’s piece at the Chronicle, five factors are identified as contributing to the decline in reading:

A decline in academic expectations during and after the pandemic has led to learning loss, recent assessments show. A 2023 EdWeek Research Center survey found that 24 percent of secondary-school officials described the loss of learning in English and language arts as severe or very severe. And 15 percent said the same about social studies.

Additionally, a generation of students may have been harmed by problematic reading-instruction strategies used in many elementary schools. Rather than learning the building blocks of words through phonics, they were taught to rely on context clues — an approach not backed by research.

Testing culture also discourages deep reading, critics say, because it emphasizes close reading of excerpts, for example, to study a particular literary technique, rather than reading entire works.

Young people are reading less for pleasure, too. In 2020, only 17 percent of 13-year-olds surveyed said they read for fun almost every day. That figure was 27 percent in 2012 and 35 percent when data collection began in 1984, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

The ubiquity of smartphones and social media have also affected literacy across the board. Children and adults alike are reading in fundamentally different ways. For one, phones have been shown — to no one’s surprise — to interfere with our ability to focus. And apps such as TikTok, Facebook, and Instagram have shifted our reading habits toward short and often fragmentary text.

Pandemic-related learning loss, bad educational theories which proliferated when this generation was learning to read, the ubiquity and intensity of testing culture, the decline of pleasure reading, and the omnipresence of smartphones all factor in the problem.

In brief: reading is difficult, many students were failed in their educations, and many lower-effort forms of media exist. So, students don’t read. And it seems that few of them have found the beauty and joy of reading, and so they lack the desire to read as well.

But I think there is a sixth factor which we have overlooked. It is a kind of gatekeeping — except it is students who are gatekeeping themselves. And this gatekeeping continues well into adulthood.

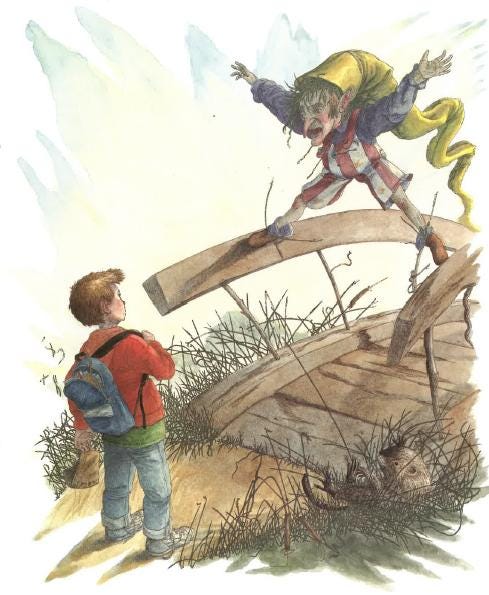

For those who don’t imbibe modern slang, I’ll give a brief explanation. ‘Gatekeeping’ has become one of the accusations du jour. Anyone who places any sort of boundary on something – a community, a hobby, an identity – will be called a gatekeeper. Images of a troll standing in front of a bridge refusing to children safe passage come to mind.

Gatekeeping is usually conceived of as an interpersonal violation. The gatekeeper is preventing someone else from being included in whatever is at issue. But very often, the person who is preventing you from crossing the bridge (to go back to the troll metaphor) is you. If you want to read The Economist, say, but don’t because you don’t think you fit the profile, then you are your own troll. You are the one doing the gatekeeping, and the person being kept out is you.

And this is what I believe is happening with students and reading, at least in part. They have convinced themselves that they aren’t readers. They have convinced themselves that reading old books, especially difficult old books, is just too arduous, too boring, too pointless. They have convinced themselves that even if the books are good and soul-enriching, there are better things to be doing with their time.

My son is roughly a year old, which means he is starting to walk. He still can’t make it across the room, but he can take a few steps. He has a peculiar habit of eating bananas while standing. This usually means he holds a large chunk of banana in one hand while using the other to hold on to the table. Sometimes, overcome by banana-eating euphoria, he will let go of the table he’s using for stability, and he’ll just stand. Then he notices what he has done, and he promptly falls down. It is reckless to attribute complex thoughts to a developing child, but it seems like he is able to stand until he remembers that he can’t. It’s like his conscious thoughts are preventing him from walking around the room.

This may not really reflect my son’s inner state (I keep asking, but he refuses to confirm), but it is a decent metaphor for our declining reading culture. My suspicion is that many of these students would be able to read difficult books, and read with a greater sense of clarity and appreciation for complexity, if they could get beyond the thoughts that are holding them back, if they could just stop gatekeeping themselves.

I sometimes see this in YouTube comments. When I recommend Plato to beginners in philosophy, I am told that I am being irresponsible, because Plato is too difficult for a beginner. It would be better to recommend a comprehensive survey of philosophy explicitly written for beginners, the critics say, so that people don’t get overwhelmed.

But then I see other comments, sometimes on YouTube but often elsewhere, from people who had never read any philosophy, stumbled on one of my videos, and read Plato. Sometimes these are high school students, sometimes college graduates who did not study philosophy, sometimes mid-career adults who didn’t bother with college. The message is remarkably similar. They were previously convinced that philosophy would be too difficult to them, and reading Plato helped them see that they were wrong.

In some cases, these new students of philosophy had been told by someone else that philosophy wasn’t for them. They had been told it is was too dry, too boring, too dead and white to be of interest. They had been told that philosophy was for a select class of people, and that they were not in that class.

In other cases, these students told themselves that. They were the gatekeepers and the victims. But the patterns of thought were not original to them. They were mirroring the kind of thinking that they’ve encountered throughout their education.

The lesson I’ve taken from this is that we often prevent ourselves from doing what we’d like to do, what would be good for us to do, and what we are in fact capable of doing based on narratives we have imbibed. We accept the common story about the ancients being too difficult or too alien, and so we start to think of those books as something for people who are smarter than us.

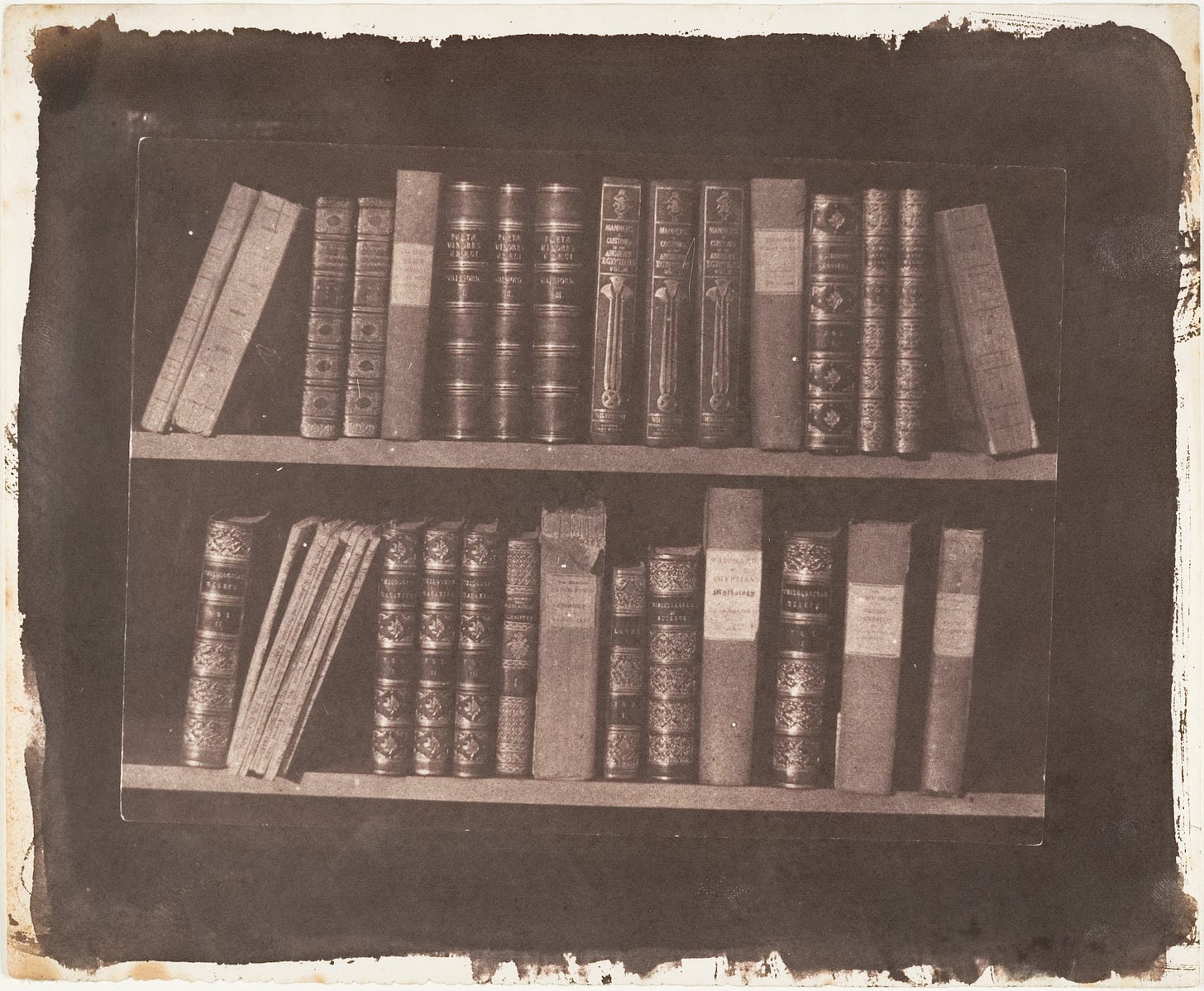

So we see a stagnation in reading development and a general decline in a culture of letters. Old books become something for a rarefied class – probably people with two PhDs and half a dozen master’s degrees – and we resign ourselves to the lower rungs of the literacy ladder. Or we just give up on reading altogether.

Students didn’t manufacture this narrative themselves. I think they’ve been imbibing it since they were born. Books were divided into increasingly granular reading levels. Students had to earn their way to the next level. Eventually they stagnate, or their progress slows, and they start to few those far-off bookshelves as always out of reach. Reading those books isn’t for them; maybe reading isn’t for them.

Narratives are how we conceptualize the world. Certain narrative links – links between events that we add in to help explain the world – are picked up through mimesis. We see others think of the world in a particular way, and we start to conceptualize the world in similar terms. And the best solution to a harmful narrative is a more enriching narrative. You have to have a replacement for the narrative you are trying to rid yourself of.

The narrative around reading now is that the classics, the great books, are either hopelessly difficult or hopelessly outdated. There is a kind of chronological snobbery at play, but that is only part of it. There is also the idea that back then writers didn’t bother to be accessible, that they take too much for granted, or that they just weren’t very clear. And there is an idea that anyone from an earlier time cannot speak to our modern difficulties or preoccupations.

A few associations are enforced by this narrative. What is new is to be preferred to what is old; that which is accessible is superior to that which is difficult; that contemporary culture is singular, distinct, and detached from the rest of human history.

But consider a new narrative. Imagine instead that books offer us a way to enter into a prolonged conversation across generations. We might even call this the Great Conversation. Imagine instead that authors have generally meant well, and so when they produced difficult works it is because the subject matter is a difficult one. Imagine instead that the past is a kind of mirror for the present, and that history is a guide to the future.

New associations are encouraged by this narrative. New works are continuous with old works; both new and old works have something to teach us; difficult works might be more insightful because they engage with the complexity of the world.

Children need to learn to read difficult books, or else once they are in college they won’t be able to do so. That probably means that they need to attempt to read some of these books, even when we know they will likely fail.

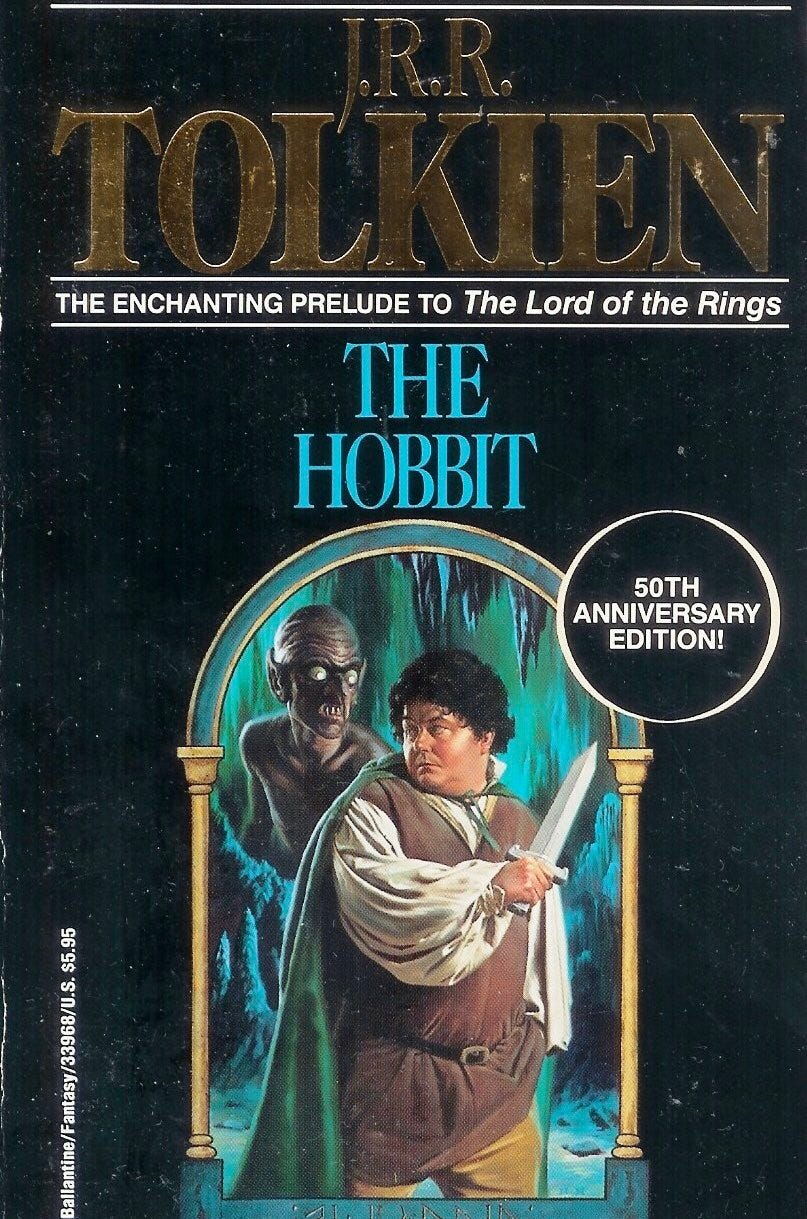

I was a precocious reader, and I was always hungry for new books. I was in third grade when I told my father I wanted to read The Hobbit for myself, and he lent me his old, battered copy. It was the 50th anniversary edition, and it was hideous.

(This must’ve been my father’s third or fourth copy, since it came out in 1987.)

It took me quite awhile to read it. I don’t remember how long, exactly, but I remember taking it everywhere for a long time. It was a struggle.

The book is rated at an advanced sixth grade reading level, so it was a few years too advanced for me. You can imagine what a certain kind of teacher, meaning well, might have said: why don’t you read this first, then you can read that when you’re ready. I am tremendously glad no one said that to me. The Hobbit made me feel like a new world of books was opening up before me.

The worry most people have with this suggestion is that children are going to get discouraged if they fail. But that is not necessarily the case, and I think teachers, parents, and other adults have a great opportunity to help prevent this. If we demonstrate that needing to put down a book for awhile is not a failure, then we can help children become more willing to experiment and to try things which are currently just out of reach.

But this means something else needs to change. We have to rethink our relationship to metrics.

We like to measure our successes, and when we don’t measure up we consider it a failure. This carries over into adult reading culture still — people set ambitious reading goals based on books or pages, and they feel good if (and only if) they meet those goals. It’s a metrics-based way of looking at the world. This culture is everywhere, and students are sensitive to it.

When I was teaching at universities, I found that students were grades-obsessed. They had been tested and measured from nearly the beginning of their education, and so the metrics became what they valued. What the metrics were supposed to measure – increased competency, knowledge, etc. – was no longer considered valuable. The measure tends to subsume that which is measured.

If we worry about metrics, like worrying about just the number of books we have read this year, then we are priming ourselves to prefer easy, accessible books. We won’t ever let us ourselves be challenged, because we might fail, and thus we won’t have gained anything of value.

But that is the key mistake. Failing to finish a difficult book is a valuable experience. You likely still learned something — and you’ve prepared yourself to read it better in the future. Students can be taught that failure is, in this sense, not a failure at all, and that their frustrated attempts may be as rewarding as their successes.

As someone who came to philosophy later in life without any formal education, this gives me a lot of hope that there is a place for me in the Great Conversation. Thank you! I love the image of your son being so enraptured in the banana that he forgot he was scared of falling. What an excellent metaphor for the effect the wisdom of philosophy has on us.

I think there is something to be said about the association between classic literature and high school English classes that brings about a weariness. I only really started reading again in 2021 and that was mostly to help research for my history podcast. I had a list of classics I wanted to read, but "knew" each would be a slog. It wasn't until I listened to Crime and Punishment that I realized how the problems that are often examined in classics are timeless. This was a revelation to me. I now have too many books to read and not nearly enough time (and the distractions we all face do not help). There are still some books that scare me, but I'm more open to them than I was three years ago.

On the note about kids reading, I have begun reading little golden books to my 9-month-old every night and can't wait for the day to read the Hobbit, or Narnia, or Earthsea to her and my future kids. If all I can do is make a few more avid readers in the world, I will have been successful.