On Sunday evening, a group of us met via Zoom to discuss where we were in Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition. You can find a recording of that meeting down below.

If you want to join future calls, become a paid subscriber. In 2025, I plan to host extra calls that are more friendly to non-American timezones. Details will be announced when I have them.

These meetings are always fun, and in part that’s because people bring very different ideas to the text (and thus ask very different questions). I wanted to read The Human Condition for two reasons: I’m interested in the philosophy of work, and I’m skeptical about easy narratives around tech progress. But those aren’t necessarily the concerns that are driving the rest of you; these meetings always make that clear.

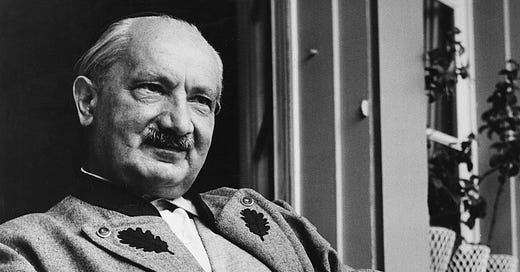

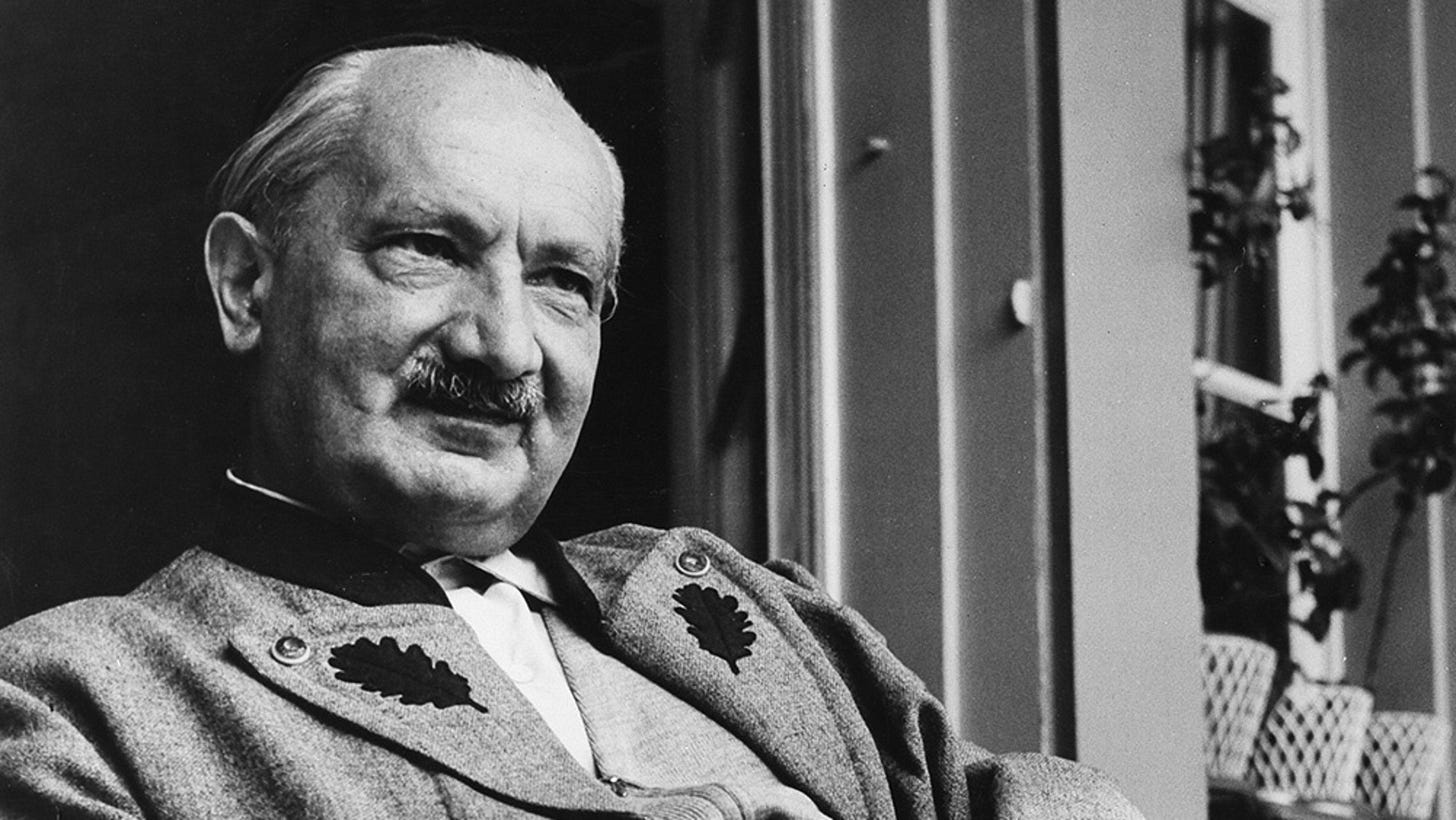

Early on in the meeting, I brought up some biographical details surrounding The Human Condition, which I drew from Samantha Rose Hill’s little biography Hannah Arendt. Hill points out that there is a specter haunting The Human Condition: Martin Heidegger, Arendt’s former advisor and lover.

This note was found in Arendt’s archive, hand-written and simply signed ‘Hannah:’

Re Vita Activa:

The dedication of this book is omitted.

How could I dedicate it to you,

trusted one,

whom I was faithful

and not faithful to,

And both with love.

We know that Heidegger is the ‘you’ here, as Arendt sent a copy of The Human Condition with the following note:

You will see that the book does not contain a dedication. If things had ever worked out properly between us – and I mean between, that is, neither you nor me – I would have asked you if I might dedicate it to you; it came directly out of the first Freiburg days and hence owes practically everything to you in every respect. As things are, I did not think it was possible, but I wanted to at least mention the bare fact to you in one way or another. All the best!

Even if we did not have this biographical evidence, though, I think we could detect echoes of Heidegger. Arendt’s skepticism of technology, her concern with how we live in the world, her discussion of man as tool-maker, her seeming side-stepping of traditional metaphysics — all of this reminds me of Heidegger, even with my rather oxidized memory of Heidegger’s Being and Time.

Yet, I don’t think I’ve noticed a single reference to Heidegger in the text; there are plenty of explanations for this, but it adds a layer of mystery to reading The Human Condition.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Commonplace Philosophy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.