"If anyone is entitled to tell lies, the rulers of the city are" | Plato's Republic, Book 3

Socratic irony, banning the Mixolydian, the guardians and their lies

Welcome to the second installment of our read-along of Plato’s Republic. Here’s the schedule:

March 31: Book I

April 7: Book II

April 14: Book III

April 21: Reading Week

April 28: Book IV

May 5: Book V

May 8: Members-Only Zoom Call, 3PM Eastern

May 12: Book VI

May 18: Members-Only Zoom Call, 8PM Eastern

May 19: Book VII

May 26: Reading Week

June 2: Book VIII

June 9: Book IX

June 16: Book X

June 22: Members-Only Zoom Call, 8PM Eastern

All main posts are free, but Zoom calls and supplementary posts are available only to paid subscribers. If you’d like to join those calls or read everything that I write, please consider supporting my work.

And as a reminder: next week, there will be no post about The Republic, as that’s a Reading Week. If you’ve fallen behind in the reading, that’s your chance to catch up!

The Republic begins with a discussion on aging. It is easy to overlook this discussion as we get into the more interesting bits, but let’s revisit it briefly. Cephalus, as he speaks to Socrates, gives a defense of the value of old age. (Though Socrates is already inclined to agree with him, the text indicates.) Many complain that old age leads to disenjoyment of many things that previously gave one great pleasure. Of particular interest is sex. Cephalus says that:

It is with the greatest relief that I have escaped it. Like escpaing from a fierce and frenzied master…Old age is altogether a time of great peace and freedom from that sort of thing. (329c)

It is not a great focus of the discussion, and they move on quickly. But this theme returns in Book III, when Socrates claims that the guardians of their new city must never be offered sexual pleasure (403b). In fact:

You will pass a law to that effect, presumably, in this city you are founding. A lover can kiss his boy friend, spend time with him and touch him, as he would a son—for beauty’s sake, and if the boy says ‘yes.’ Apart from that, his relationship with the boy he is interested in should never allow anyone to imagine he has gone any further than that. Otherwise, he will be condemned as uneducated, and blind to beauty.

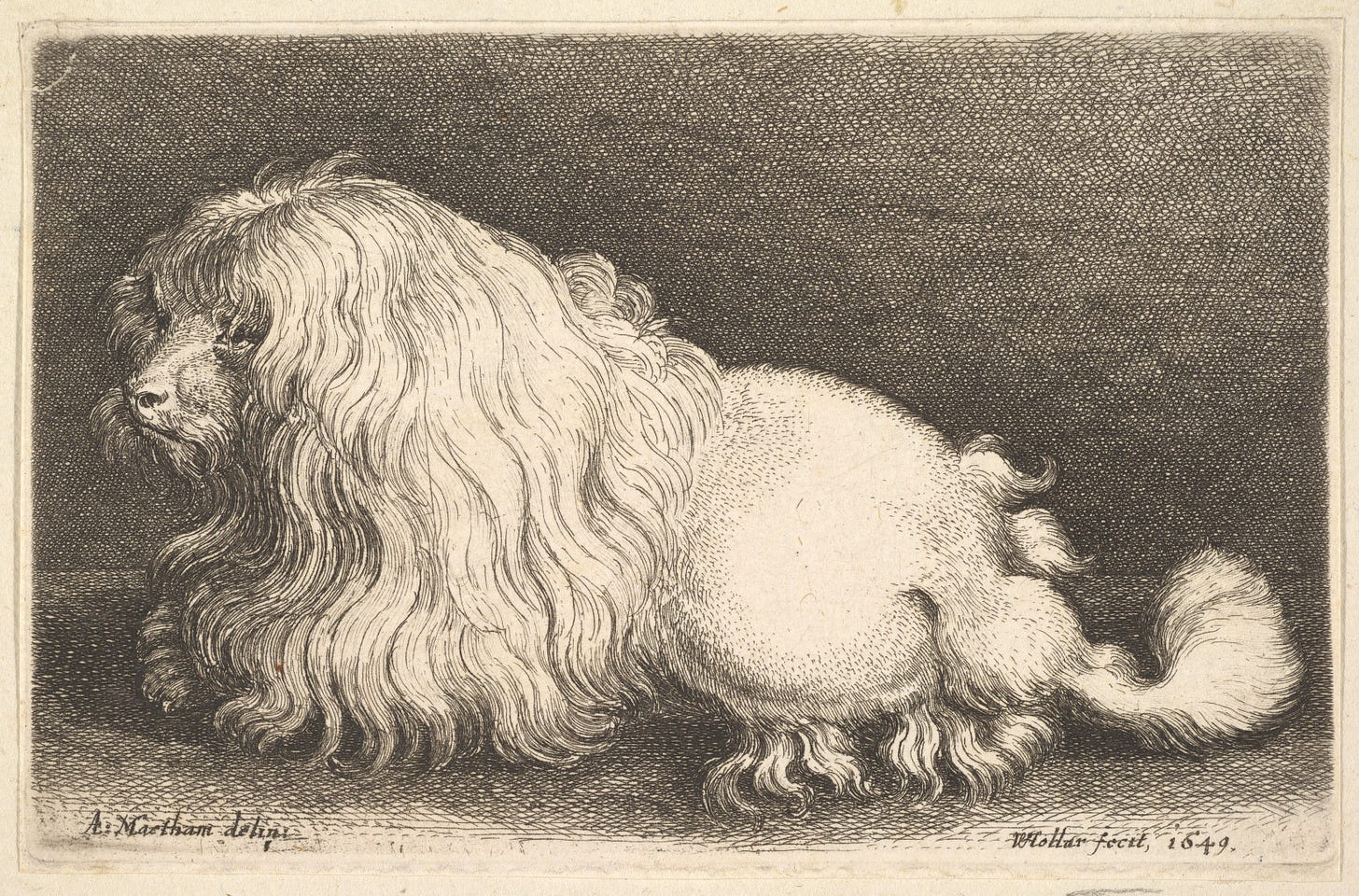

And Glaucon agrees that such a law should be passed. This is just one example of the strictures that Socrates lays down for the guardians, those men who will be like dogs – keen-eyed, vigilant, loyal to the familiar – for this city they are founding. Socrates and Adeimantus discuss three classes of stories:

Those involving the gods

Those involving demigods, heroes, and the dead

Those involving mankind

With each discussion, more restrictions are identified. Only the stories conducive to the flourishing of the guardians’ souls are permitted, and even the manner in which the stories are told is regulated. Poets will not be allowed to imitate villains, for instance, but must only describe them indirectly. Music and rhythm are placed under similar restrictions (399d, e.g.). Certain modes are banned as well as certain instruments.

Last week, we saw that Socrates would ban any stories about the gods depicting them as less than ideal, and certainly any stories involving them telling falsehoods. This should make a remark that Socrates makes near the beginning of Book III seem rather odd: lying is something permissible for the guardians (389b-c), though it is impermissible in the city for all others. The guardians, who are being raised to value beauty, truth, etc., are allowed to lie.

It seems that Socrates himself is allowed to lie, or perhaps to be ironic, in this part of the dialogue — and this comes in two ways. This should make us consider how sincere the description of this city really are.

First, let’s look at one of the texts which Socrates would censor in the city:

I had rather labour as a common serf,

Serving a man with nothing to his name,

Than be the lord of all the dead below.

This is a quotation from Homer. Achilles is speaking to Odysseus in the underworld, telling him that whatever honors he may have in death pale in comparison to any form of life. This text is to be censored because it would inspire the guardians to fear death, thus compromising their bravery in the defense of the city.

But if you look ahead to Book VII, in which we’ll encounter the allegory of the cave, you’ll find someone quoting this exact passage as evidence. That someone happens to be Socrates. The philosopher will reinterpret the meaning of this passage to apply to the one who has escaped the cave and entered the world of light and truth—no matter how good the cave might be and how uncomfortable the true world can get, it is to be preferred over the pleasures and honors one can accrue back in the cave.

So when Socrates permits the guardians to lie, and in fact lays down a myth to be used in their education, we should wonder what it going on. (Another small example: Phoenix’s advice to Achilles is censored, but Socrates calls it sound [390e]).

There is one other oddity in Book III we should keep in mind. Socrates sometimes calls this ‘our reasoning’, implying he agrees. But other times he calls it ‘your reasoning,’ implying distance. I think this is intentional on Plato’s part. The irony of the text should not be overlooked; it would be a mistake to look at this and simply accept these as Plato’s beliefs. Something else is going on.

So, like the guardians, we should stay vigilant in our reading.

Here are some of the best comments from last week’s post.

Brock writes:

One of the things that struck me about Book II was an explicit shift in the methodology of their inquiry. In Book I, Socrates tells Thrasymachus, "Please don't answer contrary to what you believe, so that we can come to some definite conclusion." (346A)

Then in Book II, Glaucon explicitly states in several places that he does not believe the position he is arguing for. "It isn't, Socrates, that I believe any of that myself." (358C) And Socrates accepts his playing devil's advocate.

Brock takes this as more evidence that Book I was originally a distinct work (which may be true). But given what I wrote above, let’s also consider that it marks a shift in how Socrates will argue. I don’t think he is necessarily saying what he truly believes.

From Ronald:

I find it interesting that Socrates proposes propaganda, or disinformation, in the ideal city. Socrates suggests that carefully crafted myths can shape citizens' beliefs in ways that support a just society. It is something that is necessary to promote harmony and unity in the city. It raises ethical questions of:

Is it ever justified to deceive people for the greater good?

Should the state regulate cultural narratives to shape morality, or does such censorship limit intellectual freedom?

Yes, certainly these are good questions. (I tend to take a hard line on both of these, personally, answering in the negative.) But maybe we should revisit this given what we’ve read in Book III!

EncryptedLore asks:

I've noticed something when Socrates is talking about the stories about the gods that is confusing me a bit. When talking about the gods, Socrates sometime says "the gods" and sometime "god". Is there some kind of singular god in Greek mythology that I'm not aware of? Or is he only talking about the concept of "god"?

This was something I noticed as well. You might think it is a significant difference, but here’s something from another commenter:

C.D.C. Reeve chooses, in his own independent translation for Hackett (rather than the one he edited and revised, also for Hackett) to translate "ho theos" (literally "The god") as "the gods," arguing that "The definite article is almost certainly functioning as a universal quantifier, as in 'The Swallow is a migratory bird,' which means (all) swallows migrate." Other translations like Bloom preserve the singular religiously as "the god," and I believe Bloom argues that this is a callback to Socrates referring to Apollo as "the god" consistently in the Apology.

Raymond wrote an extended comment, and it proved hard to excerpt, so go back to last week’s post to read it. He links Plato’s seeming authoritarian tendencies to the American political situation. But he also writes:

I, for one, do not want to live in a world without the poetry of Homer and all the subsequent writers he influenced; Virgil, Dante, Tolstoy, Joyce, Eliot . . . .

And this is a small but important point. A world without Homer, even in service to some ideal city, is a world with much less beauty.

The big interpretive question for Book III (and the second half of Book II) is how seriously we're supposed to take the program of censorship that Socrates proposes.

Jared points out one piece of evidence that there's at least some irony here. I noticed another piece.

The whole discussion of the second city (with a professional military class) kicks off because Glaucon doesn't like the food in the first city. "It seems that you make your people feast without any delicacies." (372C)

So Socrates agrees that they will design a city that will have "all sorts of delicacies, perfumed oils, prostitutes, and pastries." (373A) It seems that they are designing Las Vegas.

But in Book III, when discussing what sort of music will be allowed, Socrates says, "By the dog, without being aware of it, we've been purifying the city we recently said was luxurious." (399E)

And then they get around to the diet that the guardians will have. It will not be the sort of food that Glaucon was wanting. "Nor, I believe, does Homer mention sweet desserts anywhere." "If you think that, then it seems that you don't approve of Syracusan or cuisine, or of Sicilian-style dishes. I do not." "What about the reputed delights of Attic pastries? I certainly object to them, too." (404C-D)

No prostitutes either. "Then you also object to Corinthian girlfriends for men who are to be in good physical condition. Absolutely." (404D)

You can almost see Glaucon's disappointed face as he agrees to all this.

I like in the music conversation (401d-e), "rhythm & mode penetrate more deeply into the inner soul than anything else does...since they bring gracefulness with them...anyone with the right kind of education in this area will have the clearest perception of things which are unsatisfactory." First as a musician I obviously like this train of thought of music getting into your soul. Second, this also previews a point made later about how good judges need to be brought up "good" (i.e. penetrated and ingrained into the soul) so in the long run able to then recognize "bad" as "external, in the souls of others."

He also uses the words attunement and harmonize throughout this Book, like harmonizing your physical with your spiritual training. It lends to interpreting much of the music talk as allegory - where the music provides the "voices of the prudent and of the brave in failure and success" basically, try to embody these traits and not the other ones.

Another point I've been toying with since we did Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics is where the Greek philosophers come down on the point of nature vs. nurture but it really seems that you need both "goodness, if its natural gifts are improved by education, will in time gain a knowledge both of itself and of evil" (409e).

Finally, I think the point of having the guardians as ascetic philosopher-knights who only get subsistence and nothing more (so as not to use their strength and cunning to accrue wealth and property, to become scum of the earth landlords) is a good one and while some commenters here appear to be fixated on state censorship, there are points like this which provide upward checks across the city's social structure. The idea here, recalling that we are using the city as a way to get at finding justice in the individual, if we reduce it all into one person, is that your bronze & iron faculties, while vital to survival, should not govern your overall spiritual being; but rather your gold & silver - your discipline, your education, your spiritedness, your appreciation for beauty in the arts and in nature, your cultivated goodness, should.

It's an interesting read because I know we're only setting this up as an allegorical/ironic/hypothetical but also trying to read between the lines to find the macro & micro at the same time. Many re-reads are warranted!