Intellectual Projects

And giving them your full attention

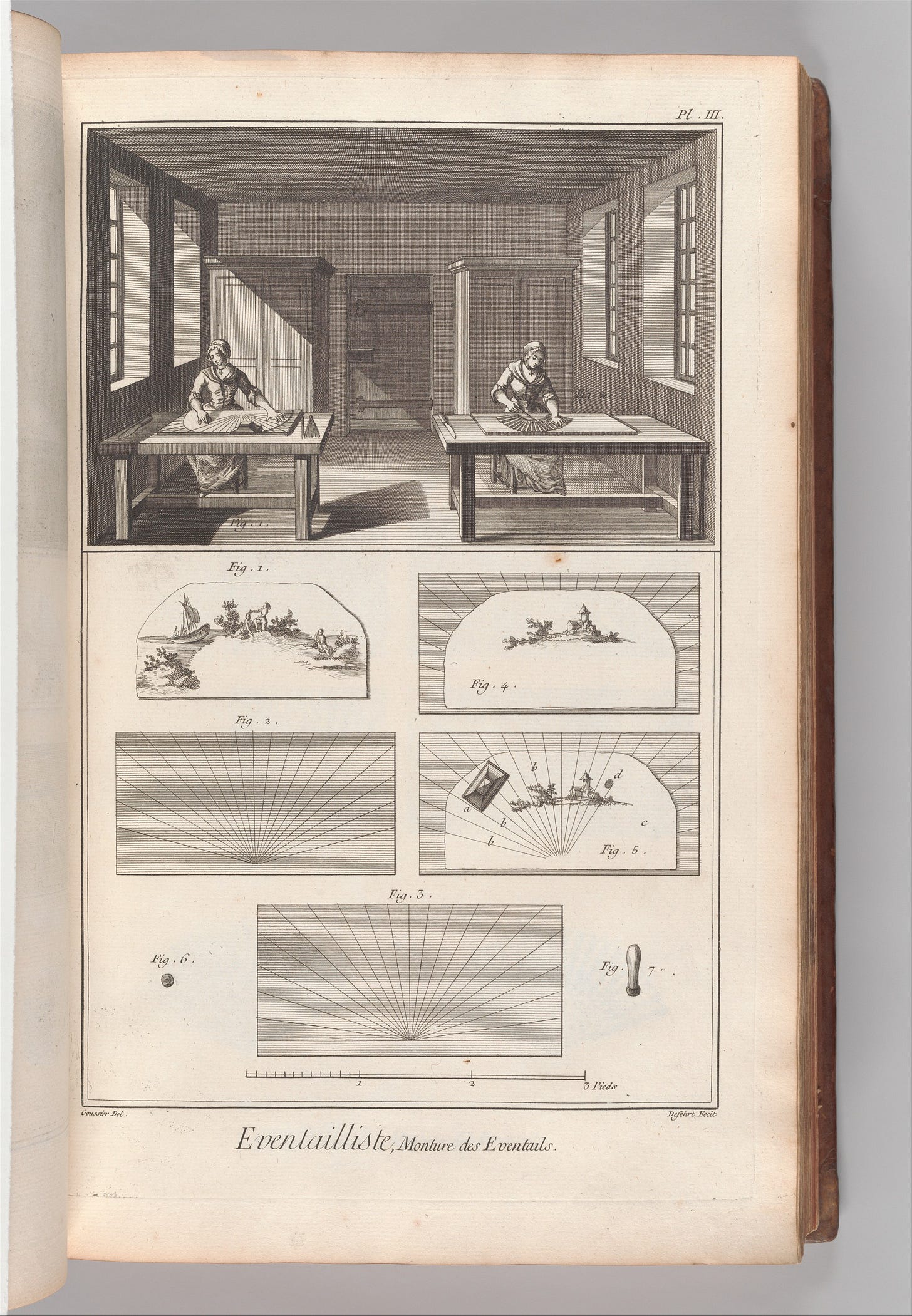

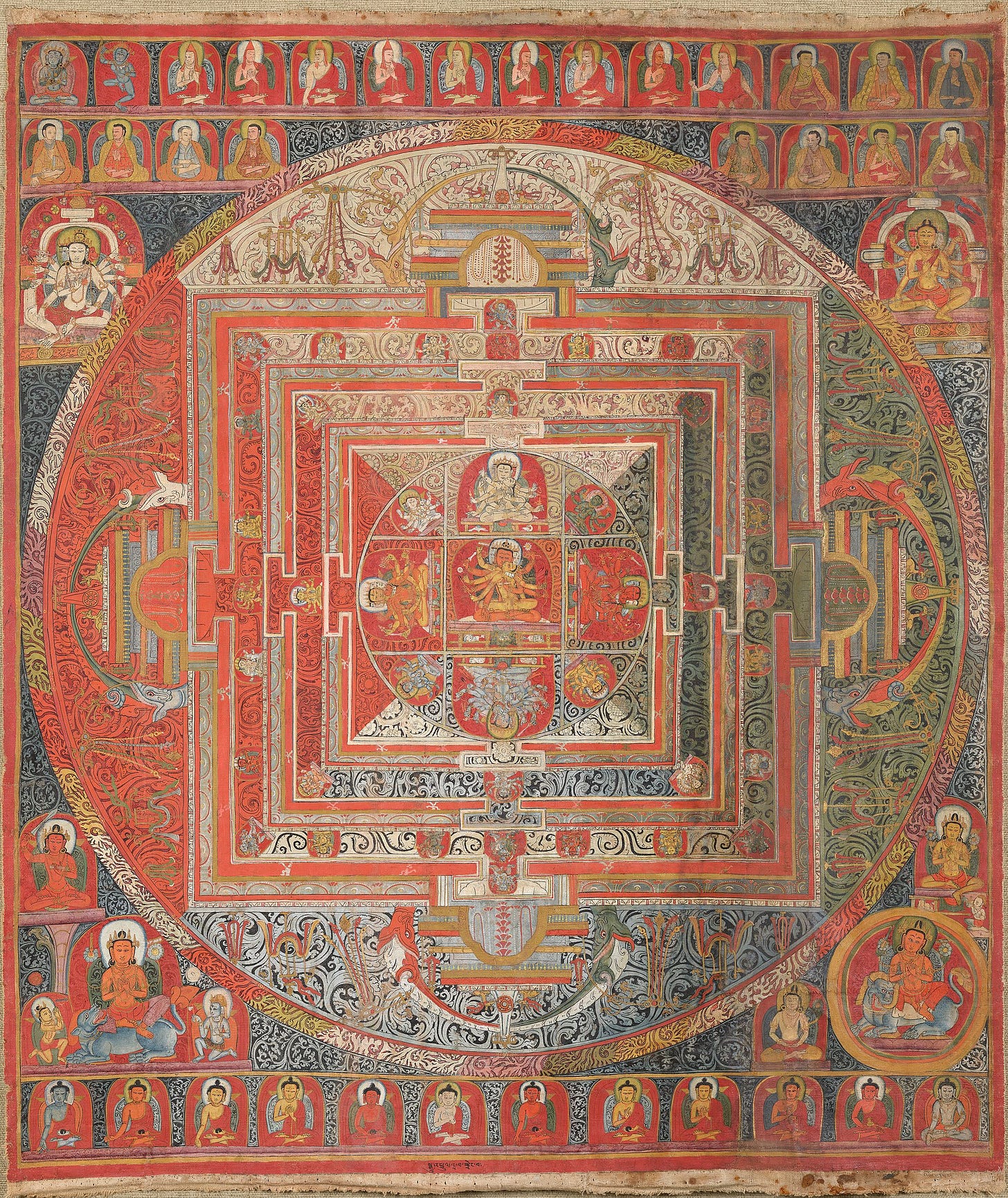

One of the more helpful ways for thinking about the life of the mind today is to frame it as an ongoing series of projects. If not a series, then perhaps a strange, mandala-like structure of overlaps, containment, and intersections. While all of it could be said to be part of the grand project – living the life of the mind – when we zoom in, we see that this singular life is made up of a (usually heterogenous) group of smaller projects.

The read-alongs we do on this newsletter could be thought of as small projects; if you’re someone who, say, wants to understand the history of women in science fiction, then our read-along of The Dispossessed is one component project of that larger project, which itself might overlap with many other projects.

All of this is to say that as you try to live the life of the mind (something I assume throughout this piece that you want to do), you’re going to find yourself engaged in a number of projects. So it is helpful to do a little bit of thinking about what those projects entail and demand.

When I was in graduate school, I was fortunate enough to study with the philosopher Lionel Shapiro. Lionel – I call him by his first name here, since one of my dissertation advisors had the same surname – could be said to be broadly interested in maybe three topics: logical paradoxes, the history of philosophy (particularly Kant, Descartes, and Wilfrid Sellars), and theories of truth. Some of these topics have obvious overlap, but others stand on their own. Lionel was able to think deeply and carefully about all of these topics, but he had to go about his work in a very particular way.

I once asked Lionel if he would be willing to meet with me to discuss something about theories of truth, the subject of my dissertation. He told me he’d gladly meet, but it would be a few weeks, maybe even a few months. He would need to get himself back in that frame of mind, he said. At the time he was teaching a class on Curry’s paradox (I was in that seminar, and it was excellent) and was just finished with a seminar on Descartes; his mind wasn’t on theories of truth at all, and this was by design.

The way Lionel worked was simple:

He would identify the topic he wanted to focus on for the next season of life. He would usually be weighing what he planned to do during this time, like teaching a seminar, writing articles, attending conferences, etc.

He would then revisit key papers and ideas from that topic as a way of refreshing his mind.

Then, he would begin in earnest. This meant careful reading (often multiple times) and the construction of an argument. As he wrote, he continued to read and refine.

Eventually, he would be done, and he would move on to the next project.

Sometimes this project would be on the same topic; in that case, the transition back to the topic isn’t going to be as arduous. But even then, I think he tended to go back to the beginning, figuring out what he wanted to accomplish and revisiting key papers and books.

I don’t think that Lionel was particularly concerned with finding the ultimate note-taking system, nor did he (as far as I can tell) have opinions on which knowledge management app was the best. I don’t think he had strong feelings about pencils or pens. I usually saw him with stacks of printed articles and a pile of books, with some writing instrument in his hands. On top of that, he didn’t seem too concerned about producing — sure, he’d write articles or teach classes, but he was far from the most productive scholar in the department.

I do think he was the most careful.

Reading with Lionel was excruciating. Near the end of my time in graduate school, he read a paper I had written that I intended to send out for publication. We sat a coffee shop on campus for two, perhaps three, hours and went over every detail. He’d underline a word and simply ask you what it meant. ‘It’s obvious’ was not an acceptable answer; he’d press you to choose one of the phrases many subtle variations. Then he’d show you how that subtle variation had a profound consequence on the paper as a whole, and indeed on the whole debate.

‘Never take it for granted,’ he once told me, ‘that everybody means the same thing by the same words.’

The care he brought to his projects was the same kind of care he brought to reading a paper. He had no hacks, no shortcuts. In fact, he seemed to recognize that there were no hacks and shortcuts. The only thing that worked was paying close and careful attention to things that matter.

I am transitioning to a new project now. I’ve mentioned before that I have a book in the works. While details are still hazy, I’m now in the thick of writing the thing (after going through months of planning and proposing). I want it to be good. I need it to be good, in fact. So, this means my project has to have my attention; I have to give it my attention.

It’s a mistake to say that we can give our full attention to anything. I have a son, and my wife and I are expecting our second child later this year. Anyone with a family can tell you that you never have a full day of focused work, and I would say that you shouldn’t want one. My son deserves my attention, too. It’s best, then, to think of your family and your work as both deserving your attention and to avoid placing them in competition — but we also have to recognize that when you pay attention to one thing, you are necessarily excluding many other things from your attention. As I write this, I’m not with my son; when I’m not with my son, I’m not writing. (And for the fact that I get to spend time writing and spend time being a father, I say: thank you.)

So, as I think about transitioning to this new project, the first step is to figure out what I’m going to exclude. Not my family, of course. But many other things are on the table.

I won’t give up on the read-alongs or writing this newsletter. I find that thinking about a text with all of you gets me excited in a way that lonely research does not. But maybe my original plan to finally crack Phenomenology of Spirit, Spinoza’s Ethics, and Plotinus’ Enneads is a bit too ambitious. Over on The Plod, I may have to focus on only one of those texts. Slow, careful reading of just the Enneads might be the respite I need, anyway.

I’m also a YouTuber, as you likely know. It is very easy to get caught up in constant posting cycles there as you chase algorithmic glory and algorithmic dollars. So there, I’ll likely need to exercise restraint. And I’ll have to find ways to incorporate ideas from the book into the videos so that I do not feel as if I am bifurcating my mind.

Other things will certainly have to be cut. I play too much chess — that’s going by the wayside for a time. I may not read quite as many spy novels as I’d hoped for this year. Nights I’d spend with a whiskey and a science fiction novel might be spent with my research materials and a legal pad.

This can all sound rather dreary, but I don’t intend it that way. I may be temporarily sad about playing less chess while I write the book, but it helps to remember that this is a small price to pay for writing a book. I’ve dreamed of holding my own book in my hands since I was a small child. With some hard work and dedication, that dream will be realized. And when I look at the book, I want to think to myself, ‘This is a good book, and I did well.’

And to be able to do that, I need to give this project my attention. Looking back on my time in school, I already have a model to emulate.

It’s time to start a new project.

Great post Jared, so true and such powerful, grounding advice for those of us who feel at the mercy of distractions and interruptions and the constant chase of the ever-better hack.

Hey now, those spy novels have a purpose. I find that I need something low-key and unchallenging at night to wind down before I go to sleep - otherwise I'm up half the night thinking about stuff that I picked up from the heavier texts.