For the rest of August, I’m offering a 20% discount on annual subscriptions to Walking Away. To subscribe and support my work on Substack and YouTube, just go to this link.

In high school, I started getting into what I considered ‘real’ music. No longer content to listen to the various greatest hits CDs my mom had gotten me on trips to Sam’s Club, I started to find music for myself. I wouldn’t have admitted it then, but I had a rule: the more obscure, the better.

Eventually, I found this book: Our Band Could Be Your Life. A chronicle of various underground bands in the 1980s, it introduced me to The Replacements, Fugazi, Mission of Burma, Dinosaur Jr. — essentially, it was my introduction to a style of music that is sometimes called ‘college rock.’ I fell in love with the book and the bands and the stories about the bands. Some of these bands are still favorites of mine.

It is impossible for me to hear the opening bass riff to ‘Waiting Room’ by Fugazi and not smile. Learning the guitar hook from ‘Repeater’ is a memory burned into my brain. Drumming along to ‘Alex Chilton’ is always a good time.

But something else happened to me around that time: I became insufferable. My music tastes were an excuse for me to be a jerk, and I used that excuse quite freely. Oh, I would say, you wouldn’t know about this band. They aren’t very popular.

‘Popular’ became an epithet in my vocabulary. The idea that popular music could be good was an impossibility. (In my ignorance, I hadn’t even listened to Pet Sounds, proof that pop music can be masterful.) Eventually, I was just unpleasant to be around.

You might think that the moral of this story is that we need to abandon all snobbery and elitism. Perhaps we can embrace ‘poptimism’ and pretend that all music is equal in quality and value. But I think the real lesson isn’t that I needed to stop being a snob; I needed to learn how to be a good snob.

I contend that being a snob is a good thing. Snobs have discernment. They can tell the good from the bad. Snobs take art seriously enough to judge it; they ask difficult and probing questions about their own reactions to books, music, cinema, and the like. But if you’re a bad snob, as I was in high school, then what you have done is merely pretend to have discernment. You don’t ask interesting questions — you might not ask any questions at all. You don’t have good tastes; you just imitate those who do. Being a good snob takes time and effort; you have to be exposed to a wide variety of art, and you have to think through your own reactions to it. Being a bad snob is easy; it is knee-jerk art criticism for those who like to put others down.

Let’s think about another example: literature. I love novels we call ‘classics’ — the idea being, of course, that these books are some of the best that have ever been written, and so we have kept them around. But I also love speculative fiction: science fiction, fantasy, the weird fiction of the turn of the century, and so on.

If you went to a bookstore and took a random novel off of the classics shelves(if you’re lucky to have a bookstore with a separate classics section) and a random novel off of the speculative fiction shelves, the odds are heavily in favor of the classic. It will likely be a much better book. There are many explanations of this – importantly, classics as a category involves a strong quality filter in the act of preservation – but the explanations themselves aren’t that important just yet. The basic insight we need is that even if you like both genres (if classics can be called a genre), you can tell that the books on one shelf tend to be better than the books on the other shelf.

This raises the hackles of many speculative fiction fans and writers. Ursula K. Le Guin used to get quite upset about the matter. And some of her points were quite good — the assessment of the genre common in her time had very little to do with the writing or the quality of the books but rather was a dismissal of the genre as inherently worse than more realistic fiction. ‘Inherently’ is the key term here. The assumption was that there was just something about speculative fiction that made it worse, and that assumption was wrong.

That was bad snobbery.

There is nothing intrinsic to the genre that would make speculative fiction worse than the sort of books that get shelved under general or literary fiction or even the classics. Just because your books involve spaceships, warriors with ornate swords, or a premise out of the Twilight Zone does not mean your book cannot be excellent.

Further, just because your novel is self-serious, grounded in the social life of contemporary New York (or LA or whatever), or ripped from the pages of your journal does not mean that it has literary value. It might get called literary fiction, but it can still be just plain awful.

But this does not mean that we should not judge speculative fiction. We need to hold it to a standard, and I would say that we should hold it roughly to the same standard as the classics or literary fiction. By doing so, we’re still being snobs — but we’re being snobs of a very different sort. We’re being snobs who are taking literature seriously, even in its speculative form. This is good snobbery.

So let’s talk about three dimensions of a book we might critically assess.

First, the quality of the prose. A great book must be well-written at the level of the sentence, paragraph, and passage. People often assume that prose quality is a matter of vocabulary or ornamentation, and so they think I mean something like so-called purple prose. This is incorrect. A great writer might have sparse, bare prose. The point really is that the prose must serve the story and the novel as a whole. Jane Austen is a master of English prose, and I do not think we would call her writing particularly ornate.

Consider this passage from Sense and Sensibility.

When he was present she had no eyes for anyone else. Everything he did was right. Everything he said was clever. If their evenings at the park were concluded with cards, he cheated himself and all the rest of the party to get her a good hand. If dancing formed the amusement of the night, they were partners for half the time; and when obliged to separate for a couple of dances, were careful to stand together and scarcely spoke a word to anyone else. Such conduct made them, of course, most exceedingly laughed at; but ridicule could not shame and seemed hardly to provoke them.

This is a series of well-crafted sentences. ‘When he was present she had no eyes for anyone else’ — a clear, direct statement of theme. The passage is about devotion, nearly obsession, the sort of feeling we’ve all felt when falling in love. The paragraph flows well, ending with a strong reminder that there is a them there. The feelings so well-invoked are mutual.

For a more contemporary example of this, just look to Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall.

But it is no use to justify yourself. It is no good to explain. It is weak to be anecdotal. It is wise to conceal the past even if there is nothing to conceal. A man’s power is in the half-light, in the half-seen movements of his hand and the unguessed-at expression of his face. It is the absence of facts that frightens people: the gap you open, into which they pour their fears, fantasies, desires.

Or this:

I have written books and I cannot unwrite them. I cannot unbelieve what I believe. I cannot unlive my life.

These are gut-punch passages, and there is no excessive ornamentation. Yet sometimes, we find that a novel needs more. Crime & Punishment is a ramble at times, but how could it not be? It is a prolonged breakdown, a dark comedy of errors. To write it like Hemingway would be a travesty.

I find that quite a bit of speculative fiction falls into a trap. Writers in the genre believe that in order to write well, you have to be excessively ornamental. When not done well, this comes off as pretentious and clunky. To avoid this, they choose a very utilitarian prose style. The prose really is supposed to get out of the way. I find, however, that the prose gets in the way — there isn’t enough care, so they repeat strange idioms, don’t seem to think about the flow of the paragraph and write scenes as mere sequences of events. Foundation, while very good in some ways, does this quite a bit.

Second, the book needs to be well-plotted. I don’t take this to mean that the book must be streamlined or anything — in fact, a book that is too streamlined is often a failure. A great plot is like a great river: there may be forks and eddies, but there is always a current.

Because speculative fiction is more sensitive to the whims of the market – since it receives little critical attention, books need to build buzz and hook readers to succeed – the books tend to have very straightforward plots. Sometimes, it is said that they are fast-paced, action-packed, energetic. But lately, I’ve felt that they are increasingly plotted like Marvel movies: short scenes, always ending with a bang, reveal, or witticism. There is little that is very interesting about the plot — and this often leads to the book suffering in other ways. After all, if a book is streamlined and action-packed, character and theme will suffer. The plots favored in speculative fiction thus can negatively impact the book as a whole.

Third, the depth of characters. Some novels take great pains to create characters who could be real human beings; these novels are, I like to say, psychologically real. Other novels like to make characters stand in for ideas. Both sorts of novels can have great characters — the trick is to make sure the characters have depth.

How does one achieve depth? There are a few ways. Giving a character an interesting history so that the reader can see how that history has made the character who she is today will do it. Embedding the character in complex relationships will do it as well. But one of my favorite ways to do it is to introduce some dissonance. If the character is psychologically real, she will be pulled in several directions. Her ideals will not always harmonize. If there is no dissonance, she will seem like a caricature.

For a novel where the characters really stand in for ideas, we give those ideas depth by acknowledging their limits and inner tensions. Where does the ideal fall short? What are the edge cases? When can we see the idea’s insufficiency? Dostoevsky, I think, is the master of this sort of character.

Some speculative fiction writers do characters well, but the way we see these characters grow and develop looks a lot like wish fulfillment. The hero must always rise; there must be a moment when he is vindicated. His weaknesses must be overcome. He must be shown, in the end, to have been right.

Fans of speculative fiction may already be typing. What about…? they will ask. And they are right to do so. I’m speaking in generalities, and the fear is that if we let those generalities become fully universal generalizations then we’ve fallen into the old trap — we’ll start to say speculative fiction is just plain worse than other forms of literature in virtue of being speculative fiction.

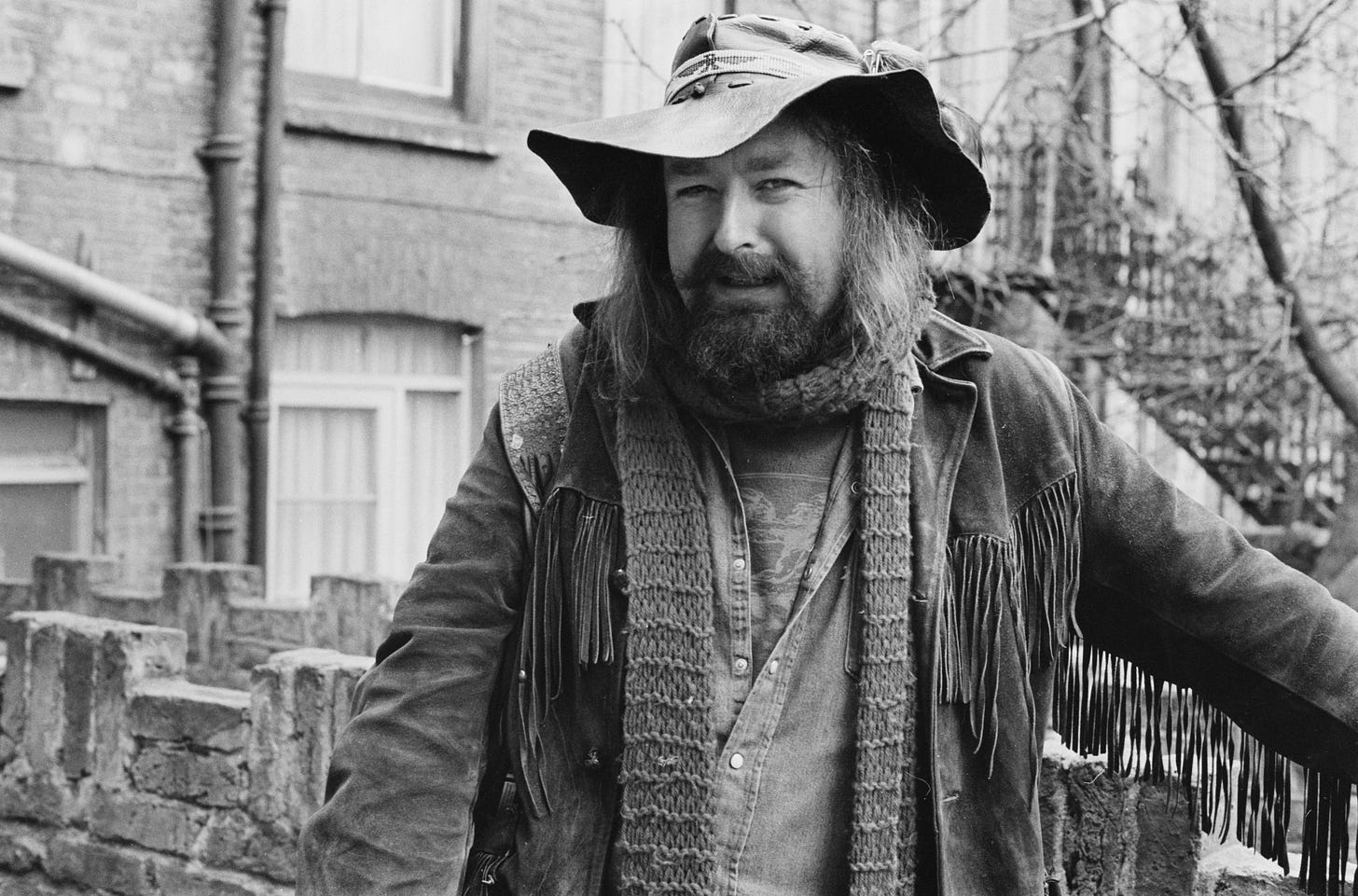

And there are some hefty exceptions that prove that speculative fiction can be great. Gene Wolfe was a masterful writer; Michael Moorcock, despite his prickliness, knows how to craft a character; Guy Gavriel Kay can write one heck of a sentence.

He couldn’t sing of Tigana, and he was certainly not about to sing of passion or love, so he began the very old song of Eanna’s making the stars and committing the name of every single one of them to her memory, so that nothing might ever be lost or forgotten in the deeps of space or time. It was the closest he could come to what the night had meant to him, to why, in the end, he had made the choice he had.

Ursula K. Le Guin is often praised for her ideas, but her prose was quite good and (this is not acknowledged as much) she had a good sense of plot. She let her characters take detours, even in short novels, and those detours help build the characters. She also had a great sense of character. The Dispossessed ends, if such a book can ever really end, with Shevek in a state of uncertainty. If he succeeds, it will be because of his ideals. If he fails, it will be because of those same ideals. We don’t know what is going to happen, and neither does he. That tells us quite a bit about the man he is.

Janny Wurts, a writer I’ve only recently been made familiar with, is another great prose stylist. Here’s a passage from the very beginning of one of her novels:

The longboat cleaved waters stained blood-red by sunset, far beyond sight of any shore. A league distant from her parent ship, at the limit of her designated patrol, she rose on the crest of a swell. The bosun in command shouted hoarsely from the stern. ‘Hold stroke!’

Notice that Wurts tells us an awful lot in just a few sentences, and she does it in a way that flows well. We know the time and place; we know this boat is in some sort of regimented order (‘designated’ would be inappropriate otherwise). We know they have been at it for some time, as the bosun’s voice is hoarse. To use the usual parlance: there is an awful lot of showing rather than telling in that passage. And it is quite enjoyable showing as well.

What these writers prove is that speculative fiction, when done well, is a wonderful thing. It can be just as good as a classic novel. I think this makes it all the more tragic that so many writers of speculative fiction don’t bother to try to improve their craft.

Because I love speculative fiction, I want it to be excellent. I refuse to hold it to lower expectations than I would literary fiction or the classics.

That has been quite a detour into speculative fiction, so let’s take a step back and think about where we are. I started by saying that I used to be a snob (and on top of that, an asshole) and that I’ve come to the position that I was a bad snob. The solution, I’ve concluded, is to be a good snob. Then suddenly, I started talking about what made a book good and bad. What is going on?

If I were a bad snob, I wouldn’t bother to talk about why so much speculative fiction was bad. I also wouldn’t bother to talk about what made great speculative fiction great. I would instead dismiss the genre entirely — just as previously I would dismiss any music I considered to be too popular or mainstream. But I’m trying to be a good snob, to practice having discernment about the quality of art while also giving my reasons. I’m trying to engage with art seriously. When you engage with art seriously, you will start to see that some of it is rather bad and some of it is excellent, but you’ll often be surprised where you find those rare bits of excellence.

It will often be in the classics section, in part because we have preserved those classics for a reason. The act of preserving a book is cultural Darwinian selection; the fittest tend to survive. But sometimes you will find a crime novel, a work of high fantasy, or a comic book that cannot be ignored. The good snob can judge those works on their own.

So let’s end with a list, admittedly written off the top of my head, of what makes a bad snob:

A bad snob speaks in extreme generalities. He dismisses whole genres or styles.

A bad snob lords his tastes over others. Art becomes a battleground rather than a carnival.

A bad snob cannot give reasons for his views. He engages in the pretense that the quality of art is obvious to those in the know.

A bad snob takes pleasure in others knowing he has the correct tastes.

If you can avoid those traps, then you can be a good snob. And I think that’s a good thing. Though, as always, try not to be an asshole about it.

This is great. I would add to your list that bad snobs often don’t understand that there is a time and place to share or critique views. Somewhere along the snobby hero’s journey, you develop that self awareness and learn that conversations about art or taste become much richer when they are welcomed in the first place!

I loved the phrase 'Art becomes a battleground rather than a carnival' - a perfect summation of what we lose when we fall into the 'bad snob' camp, a camp I was also guilty of belonging to in my younger days!