I have a PhD in philosophy, which by some definitions of ‘expertise’ means that I am an expert in philosophy. I probably wouldn’t agree with this claim, though I would argue that I am expert in a quite narrow niche of philosophy — namely debates about truth and logic, as that is what I wrote my dissertation on.

There’s this troubling tendency we have when we become experts in a particular area We think that this means we have been elected to the class of experts, the professionals who are able to pontificate on anything with authority. Of course, this is not how expertise works. I know very little about mathematics, biology, literature, history, sociology, neuroscience — I think you get the point.

In some of those subjects, however, I have an interest. I like to study them on my own, even if I cannot even aspire to be an expert. (Some areas of philosophy are like this too. I’ll never be a Hegel expert.) I am just trying to be a very good amateur.

If you stick around with this newsletter, you’ll soon read an installment of a series I call Books Worth Your Time. It is a monthly thing, in which I recommend books I think are, well, worth your time. In other words, I tell you about books I like and books you might like too.

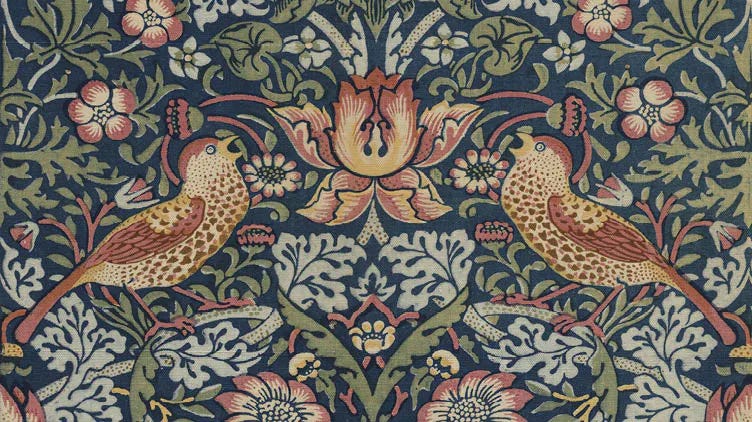

In the next installment, I’m going to talk a little bit about William Morris. Morris was a great many things: writer, artist, founder of the influential Arts & Crafts movement, social critic, and more. I’m going to tell you in that installment of Books Worth Your Time about a particular book by Morris that you should read, because it is good.

I am not an expert in the life, work, or art of William Morris. I am keenly aware of this because I am friends with an actual expert on Morris — a man who wrote his entire dissertation on Morris’ writing, in fact. I think in a previous time of my life, I would have found this discouraging. After all, I’ll never know nearly as much about Morris as my friend. What’s the point?

I used to think this about a lot of things. I reasoned that if one wasn’t going to do something professionally, or at least at a very high level, there wasn’t really any reason to do it. So if you figured out that you weren’t going to make it as a professional musician, you should stop playing music. Not going to play for the NBA? Then stop wasting your time playing basketball at the YMCA. It would be better, I thought, to just focus on those few things in which you can truly become excellent.

I was very stupid.

There is a kind of delight in becoming familiar with many subjects. You begin to spot connections between seemingly disparate fields, people, areas of interest. You learn more about your own chosen area of research by seeing the similarities and dissimilarities between it and other areas. It makes you better thinker, yes, but it is also a lot of fun. And this goes for academic subjects, for sports, for craft — for just about anything.

Christopher Schwarz writes one of my favorite Substacks:

. He’s a woodworker, a writer, and a deeply principled man. He has an authenticity to his writing that I really appreciate, and of course I love the subject matter. That’s because I too am a woodworker.But to say that I am a woodworker like Christopher Schwarz is to elide the fact that he is an expert. He visits museums just to look at the ways in which the old-timers made their chairs. He visits with masters of the craft to learn their secrets. He teaches, because he actually knows what he is talking about, and his students seem to do well.

I, on the other hand, like to make bookcases and shelves. They serve a purpose, as I have too many books. That’s really the key to my woodworking — I figure out what I need, and then I try to build it. I’m planning on building a toy chest for my son, since none I could buy met my needs. I’m building a new desk for my new office, and I’d like to learn a few new techniques while doing so. I’m very much an amateur.

And I have finally accepted that this is not just OK, but actually a good thing. I do not have the time, nor really the inclination, to become an expert woodworker. I’m just a man who figured out a bit late in life that it is fun to work with your hands. I like to build things, because when you build something you can look at it, admire it, and know that it would not exist if it were not for your time and effort. And I like to use what I built, because it makes me feel at home in a way that store-bought furniture simply doesn’t. I’m an amateur woodworker, and I like it.

I think the desire to become an expert, with its accompanying aversion to being a good amateur, holds many people back from exploring their interests. You end up with a kind of intellectual or artistic parochialism — you never want to look at what else is out there, because it isn’t your thing. But all you’re doing is needlessly circumscribing the world and all that it has to offer. You’re making yourself worse off.

By all means, become an expert in something — but don’t let that stop you from being an amateur about a great many things, too.

A relevant quote from Epictetus I turn to often: “What, do all horses become swift-running, or all dogs quick on the scent? And then, because I’m not naturally gifted, shall I therefore abandon all effort to do my best? Heaven forbid. Epictetus won’t be better than Socrates; but even if I’m not too bad, that is good enough for me. For I won’t ever be a Milo either, and yet I don’t neglect my body; nor a Croesus, and I don’t neglect my property; nor in general do I cease to make any effort in any regard whatever merely because I despair of achieving perfection."

A great quote - from Adventure Time, no less:

"Sucking at something is the first step to becoming sorta good at something."

- Jake the Dog