Today we continue our read-along of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. If you’re just now joining and want to catch up, here is the schedule we are following (with links to previous posts):

July 8: Book I

July 15: Book II

July 22: Book III

July 29: Book IV

August 5: Book V

August 12: Book VI

August 19: Book VII

August 26: Book VIII

September 2: Book IX

September 9: Book X

September 16: Retrospective

That means that today we are focusing on Book II.

This post, as with all the read-along posts, is free — anybody can read, participate, and comment. But if you want to support me in this project and read the rest of Walking Away, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Since we’re a few weeks into this read-along, it is helpful to step back and ask the big picture question: why are we doing this? This is a question that could have a few possible answers:

We find Aristotle to be interesting, engaging, and historically relevant

We want to prove that Aristotle is wrong, because it feels good to disprove great philosophers

We want to feel smart and well-read, so we read the books we’re supposed to read

We want to be better people

That last answer is the best of the lot — it is properly focused on the nature of the Nicomachean Ethics, isn’t concerned with appearances or feelings of grandeur, and is a generally healthy way to think about your life. It also happens to be why Aristotle wrote the book, as he tells us in Chapter 2 of Book II: the present subject is not taken up for contemplation, as some subjects are, but for the sake of action. “Not so that we may know what virtue is, but that we may become good,” Aristotle says.

Last week, we learned that happiness is an activity of the soul in accord with virtue. (Happiness is understand in a classical fashion, so it is more than a feeling.) We wondered, along with Aristotle, if external things were relevant to our happiness — for instance, having good descendants. We saw some differences between Aristotle and the Stoics, with Aristotle thinking there are more external necessities for being truly happy (the Stoics would call these things ‘preferred indifferents’). But the main takeaway is that first point: happiness is an activity of the soul in accord with virtue.

This means we need to know what virtue is and how we can become virtuous.

Intellectual and moral virtues

We speak of virtues in general, but really there are two different sorts of virtues: intellectual and moral. The intellectual virtues are wisdom and prudence. The examples of intellectual virtues which Aristotle mentions now are wisdom and prudence, though later in the work (I believe in Book VI) we will see a more extensive list. The moral virtues are things like justice, courage, and moderation.

A major difference between intellectual and moral virtues is in how they are acquired. Intellectual virtues are taught, requiring time and experience. (So they are not merely acquired by being told once or twice about them.) Moral virtues are habituated. Indeed, the word for moral virtue in Greek, ēthikē, is a slight alteration of ethos, the word for habit.

The virtues are not present in us by nature; we are not born virtuous. Rather, we are born with the capacity for virtue. These capacities need to be developed.

For a virtue ethicist like Aristotle, then, one of the primary concerns of an ethical theory is how one can develop those capacities. This leads to a focus on moral education — again, not just the book description of virtues, but how you can morally form someone so that they can become virtuous. For the moral virtues in particular, this means we are looking at how one can become habituated in them. This will be the focus of much discussion later in the Nicomachean Ethics, but for now we can say that one becomes virtuous by acting virtuously. But crudely, moral virtue really is ‘fake it until you make it’ sort of thing.

The role of pleasure (and a bit about the arts)

Aristotle sees that human beings are incredibly plastic — we are not set in our ways, at least at birth, and how we think, feel, and act is open to revision. By acting virtuously again and again, you develop the habit of being virtuous. You also start to think virtuously, making the right sort of judgments. And importantly, you begin to take pleasure in acting virtuously. You abstain from food and remain moderate, and that in itself is a good thing which delights you. Others abstain, too, but if they do not take pleasure in the abstention then they are in fact not moderate, though they may be moderate-in-training.

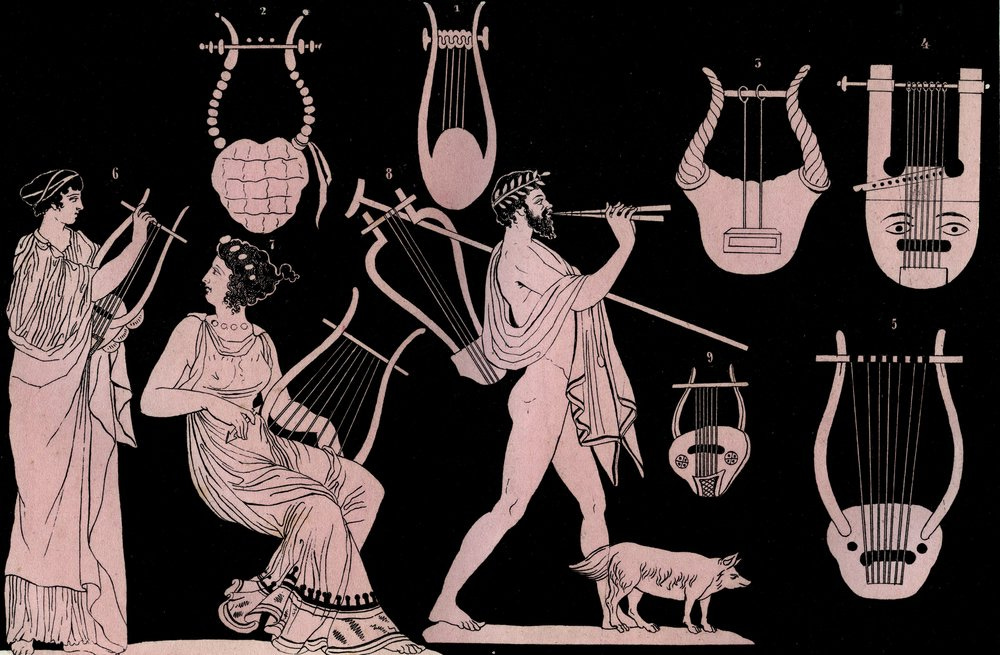

Virtue is sometimes compared to the arts by Aristotle, as both require a kind of development. Aristotle is particularly fond of a comparison with a cithara player, though this is not always the best comparison.

The comparison is a good one in that virtues typically require a kind of development, and thus acting virtuously is a kind of skill. But music feels awfully ephemeral, and so when Aristotle speaks of the good of an art because an artifact, it feels counterintuitive to think of a musical performance (see chapter 4). We think more about, say, statues. (Let’s avoid the ontology of music for now.)

Further, it is possible to create a beautiful artistic work by chance. And that is importantly different from virtuous action. We cannot be virtuous by chance, because a truly virtuous action requires that the action be in a certain state (it being the virtuous thing to do) but also that the actor be in a certain state (thinking and judging virtuously). Virtue ethics, in general, requires that someone does the right thing for the right reason.

If you find these sorts of comparisons helpful, then contrast this with utilitarianism and Kantianism. Utilitarians really only care about the right action. Kantians think you need to do it for the right reason, too. Virtue ethics, in this regard, is more similar to Kantianism than to utilitarianism.

So while you can perform moderate actions when you are not yourself moderate, what is really happening in this case is that you are becoming virtuous — you just aren’t there yet.

As Aristotle writes:

But whatever deeds arise in accord with the virtues are not done justly or moderately if they are merely in a certain state, but only if he who does those deeds is in a certain state as well: first, if he acts knowingly; second, if he acts by choosing and by choosing the actions in question for their own sake; and, third, if he acts while being in a steady and unwavering state

Virtue is the mean between vices

The back half of Book II, and in particular Chapter 6, is very important for the rest of the Nicomachean Ethics.While much of the work will focus on the particular features of particular virtues, so far we have been concerned with virtue in general. And one passage in Chapter 6 stands out in its description of what virtue is.

Virtue, therefore, is a characteristic marked by choice, residing in the mean relative to us, a characteristic defined by reason and as the prudent person would define it. Virtue is also a mean with respect to two vices, the one vice related to excess, the other to deficiency; and further, it is a mean because some vices fall short of and others exceed what should be the case in both passions and actions, whereas virtue discovers and chooses the middle term. Thus, with respect to its being and the definition that states what it is, virtue is a mean; but with respect to what is best and the doing of something well, it is an extreme.

Let’s talk a bit about what all of this means.

First, virtuous action is a choice — it can’t be pure reflex or done through coercion. This is because it is a product of our rational soul.

Second, virtue resides in a mean ‘relative to us.’ The relative clause is important here, as we are not concerned with virtue for any sort of creature, but rather for us in particular. The Nicomachean Ethics is a text written by and for human beings. (Wondering about how aliens would write their own virtue ethics is an interesting, and probably worthwhile, thing to do.)

Third, a virtue is a mean between two vices. Vices are excesses of action, and virtue sits somewhere between two vices. Consider courage. Courage sits between cowardice and recklessness. Cowardice and recklessness are vices, and courage is the virtue. But this does not mean courage is exactly in the middle. We are looking for the golden mean, the natural balancing point between the two vices. In the case of some virtues, one vice is much closer to the virtue than the other (like moderation is closer to insensibility than to gluttony).

Fourth, virtue is an extreme. You cannot be too courageous. If you are in excess, you cease to be courageous and become, say, reckless. But this isn’t because you are too courageous, but rather have deviated from courage into recklessness. This is an important point, because it allows us to say that being virtuous is always good; there is no such thing as too much of a good thing, at least when we speak of virtue.

So, what do you make of Book II? How are you finding Nicomachean Ethics? What difficulties did this week’s reading present? Did I leave something out you think we should discuss?

Let me know down below.

Hearing about virtue as a mean between two vices was pretty insane to me (in that it blew my mind). It's something that I could see the shadow of but never really had the words to say it. I also love that Aristotle says, "Hey, don't just think about this stuff, actually live it." Here's to trying to grow in virtue!

For those of us with the goal of becoming better people, the end of Book 2 leaves us with an important call to evaluate our own tendencies.

“But one must examine what we ourselves readily incline toward, for some of us naturally incline to some things, others to others.”

By identifying the pleasures and pains associated with particular activities, we can recognize the direction in which we lean and over correct in the opposite direction, therefore finding the mean more easily.

Overall I find Book 2 to be a bit more straightforward in terms of my ability to follow from point to point with less need to pause, re-read, etc. Looking forward to Book 3 and beyond!