There is a famous philosophical scenario, drawn from the work of Martin Heidegger, which I have been dwelling on lately. A craftsman – he could be a carpenter or a blacksmith in this example, and certainly doesn’t need to be a he at all – is at work in his shop, swinging a hammer. While at work, the hammer is not really a thing for him. It isn’t something which is being conceived of in terms of its dimensions, its heft, its material composition. Indeed, it may not be an object of thought at all. It is practically an extension of himself, something which when in use affords him certain opportunities and endows him with capabilities. Heidegger calls this being ‘ready-to-hand.’ Sometimes Heidegger scholars call this ‘handiness’ as well.

Then the hammer breaks, the handle splintering. The hammer is no longer ready-to-hand or handy. It is now present-at-hand, in Heidegger’s terminology. It is a thing, conceived of in terms of dimensions, heft, etc. It is no longer a tool which affords the craftsman with opportunities or endows him with capabilities.

The example is a clear illustration of Heidegger’s distinction between something being ready-to-hand versus present-at-hand. But as I have been thinking about it, I have not been thinking about our relationship to objects in general or even about the nature of tools, but rather about the conditions under which we are able to do the kind of deep, slow reflection that the human condition sometimes requires. The word which keeps coming up as I write about this – in many aborted attempts at writing this essay – is silence.

I did not realize how precious silence was until I had a son. The stereotype – disconfirmed by nearly everyone’s experience, yet bafflingly persistent – is that babies are loud. So parents of a newborn are treated as if their sleep and their sanity are under constant threat. Everyone wants to know if they are getting enough sleep and managing to make things work.

But babies are nothing compared to toddlers. As my son approached a year old, the noise grew and grew. This is good. He needs to learn to use his mouth, to get those thoughts which are forming in his mind out into the world, to express himself so that he can enter into the realm of human sociability. He needs to learn how to use his hands, which one day he’ll use to make things or to write or to play the piano, so we let him bang the frying pan against the wall a few times before we stop him. We tolerate the noise because all of the associated goods are worth it.

We were not a loud house before. My wife is a month away from defending her dissertation, and she’s been working on it for several years. I’ve always had some reason to be silent at my desk, or to be in the garage or workshop, so our conversations were usually the loudest at fixed times: dinner, before we went to bed, maybe over morning coffee. We weren’t the sort of household that just made noise throughout the day. That has changed, and I think we’re in for a few more years of growing noise before the decibels begin to decrease.

I value every moment with my son. I know when I look back in a few years, or even a few months, I’ll remember it all fondly. But he is very loud, and it turns out that I need some silence. We all do.

Before we are able to answer the question Why do we need silence? it helps to think, even just briefly, about why we say we need anything at all. When we say we need something, we usually mean one of a few different things: we need it to sustain a basic existence (that is, to keep ourselves alive and functioning), we need it to flourish (that is, to live our lives in the best way), or we need it to pursue and reach our goals (whatever those might be). The first two are objective in the sense that they do not rely on our intentions, desires, beliefs, etc. The second is subjective in the sense that it does rely on our intentions, desires, beliefs, etc. After all, two human beings will have the same rough conditions for surviving and flourishing (when we understand flourishing in an Aristotelian sort of way), but those same two human beings will have very different goals, intentions, and preferences.

Think of the simple case of food. All of us need some amount of food simply to survive, as without a baseline amount of calories we will simply wither away. We also may need food to flourish, in that we have nutritional needs for the flourishing of mind and body. But the chef, as a kind of craftsman, and the bodybuilder, as a kind of athlete, need food in a very different sort of way. For the chef, food becomes a way to pursue the craft of cooking well, and she may also have desires to try delicious and exotic foods to become better at what she does. Food is thought of very differently by the bodybuilder, who adheres to a strict calorie and macronutrient allotment in order to perform as he desires.

Now consider silence. I would be willing to grant that we do not, as human beings, require silence for our minimum survival, though this is an empirical matter. But in the second and third senses of ‘need’ – need in order to flourish and need in order to reach our goals – we need silence. For a human life that is completely free of contemplation and reflection is not a flourishing human life. And many of our goals and desires require stepping away from the world in order to pursue them.

Let’s look at two examples: Benedictine monks and punk bands.

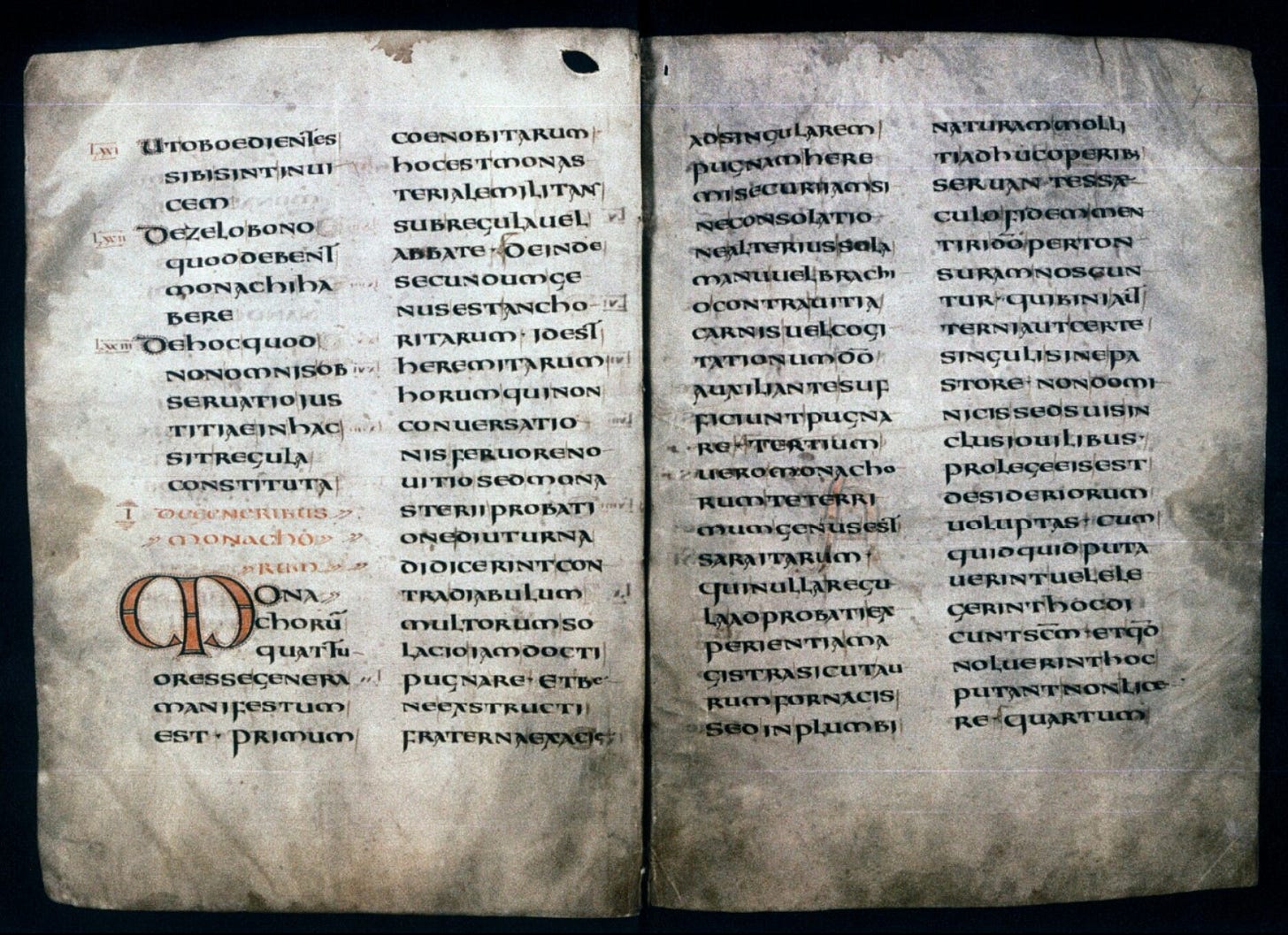

Benedictine monks, who are the oldest order of monks in the Western world, adhere to a set of guidelines laid down by their founder and patron, St. Benedict — this set of guidelines is sometimes called the Holy Rule, or more simply the Rule. This is a comprehensive rule for life in a community.

The rest of this article is behind the paywall. I discuss the attention economy, Marcus Aurelius, Matthew Crawford, the recent debates about smartphones for children, and the ways we can reclaim silence. If you’re interested in reading, consider becoming a paid subscriber. And if you liked what you read so far, consider liking this post and sharing it with a friend. Thanks for reading – Jared.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Commonplace Philosophy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.