The Vita Activa and the Modern Age, Pt 1

We’re nearly done with our read-along of The Human Condition. As you can see from the schedule, we only have two posts left.

January 27: Chapter 6 The Vita Activa and The Modern Age (§41-45)

February 3: Final Thoughts

That means we’ll soon be turning to reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. Here’s the schedule for that, with a reading load of about 90 pages per week. (But since it is fiction, I think this is quite doable.)

February 10: Introduction to Le Guin’s life and work

February 17: Chapters 1-3

February 24: Chapters 4-6

March 2: Members-Only Zoom Call, 8PM Eastern

March 3: Chapters 7-9

March 10: Chapters 10-13

March 13: Members-Only Zoom Call, 3PM Eastern

If you’d like to join those call, please become a paying subscriber. I send the Zoom links out to paying subscribers one hour before the calls, and we usually discuss the book for about an hour.

You’ll also be supporting me on YouTube, making philosophical content available to all.

I have said several times – mostly during those Zoom calls – that The Human Condition is a profoundly nostalgic book. It is a book that looks back wistfully at what we once had (or what we imagined we had), and it wonders what went wrong.

It is also a book that has for a long time refused to tell us what it is about. In part, this might be due to honest methodological considerations. On Sunday’s call, we talked about Arendt’s refusal to adopt a system or methodology, as there was something inauthentic, almost immediately false, about doing so in the modern age. But still, it can make for a frustrating read.

The first half of this final chapter seems to resolve some of these issues. Arendt has been building to something: a diagnosis of the human condition in the modern age. This is the chapter where she gives it to us. Everything else has been theoretical groundwork. The labor/work/action distinction, for instance, has all been in service of explaining the world as we now inhabit it.

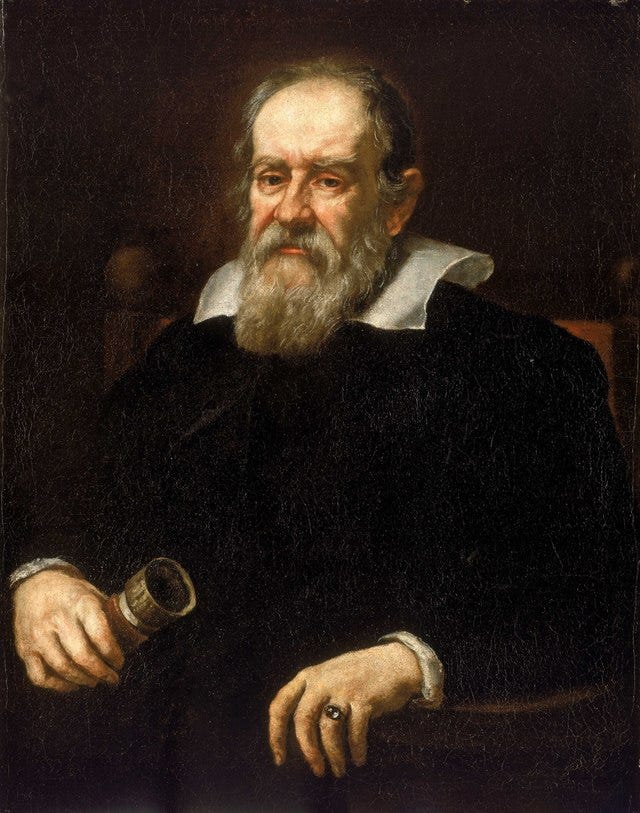

There is seemingly odd digression in this chapter about Galileo, about his proof of a heliocentric model of the solar system. Arendt treats this as an epochal event – not an idea, but an event – that shifts how humanity can find a home in the world. This makes up a large part of this final chapter. What exactly is going on?

It’s helpful to look backward, to the introduction of The Human Condition. Think of Arendt’s discussion of Sputnik, to a man-made object that now flew through the heavens and orbited the Earth. Our boundedness to the Earth was changed in that moment. Galileo’s proof of the heliocentric mode could be seen as an early first step in this progression. Our relationship to the world around us is irrevocably changed by this event.

‘World’ is polysemous, and for a long time we have gotten away with conflating two senses of the term. In one sense, ‘world’ denotes our planet. This is our world, the Earth. But in another sense, ‘world’ denotes all that there is. Even when we knew that there was more to the world than the Earth – which we’ve nearly always known – we could get away with treating the Earth as all that there is to the world. Functionally, that’s all that we could ever experience or explore.

But as we launch a satellite into space, that changes. Suddenly, there is so much more to the world.

Arendt, I think, sees us as alienated from the world. After Galileo’s proof, the Earth no longer can be seen as the center of the universe. When modern physicists say that there is a mathematical equivalency between a geocentric and heliocentric model – from different perspectives, both are correct – this does not restore the Earth to the center of the universe; it makes it just one point among many, Arendt says. There is nothing special, or even unique, about our world.

Except there is! It is ours! It is the world that we occupy and, crucially, shape. This is where homo faber comes into play, and it is where the acting man builds his narratives.

But now I think I’m seeing the crux of the book. First, we prioritized the intellectual life over the active life, which allows for a Cartesian retreat into the self. Even our mathematics becomes less spatial (we shift from geometry to algebra); we don’t think in worldly terms. Then, we invert the hierarchy of the vita activa, so that increasingly we have a world only of consumption, not of fabrication, and certainly not of action; as we learned last week, that’s a world without durability and without meaning.

We are very close to the end of this book, and things are starting to become clearer. Next week, we’ll finish our reading of the final chapter, and then one week later I’ll release my final thoughts about The Human Condition.

But we can go ahead and start having this discussion:

What have you gotten from The Human Condition?

What ideas does this make you want to explore further?

Where do you think this book falls short?

Let me know down below.

I think ultimately what I got from The Human Condition will be determined in the weeks, months and years to come. Arendt's ideas about the erosion of the public and private spheres and the rise of labor as our primary mode (and animal laborans vs homo faber), among others, are likely to lurk in my subconscious as I continue to read, think and update my model of the world and our place in it. The extent to which they ring true will probably vacillate over time.

Nietzsche and Marx are on my future TBR list, and I know that her distillations of their ideas in the book will influence my reading of their works as well. This book has definitely prompted me to explore theories of private property and really explore my own views on the topic.

Another specific idea that really intrigues me is her distinction between acting and behaving towards each other, and the notion that these days we mainly behave and rarely act. I will definitely be pondering this more.

More immediately, I already have some Alfred North Whitehead on my reading list this year, prompted by a desire to explore process philosophy/theory, and Arendt's frequent references to Whitehead have me pretty excited about digging in to his work.

Arendt offers some penetrating comments along the way but I feel there is something fundamentally wrong about her whole approach:

1) not once does she actually provide evidence or feel the need to do this. No data, no statistics of any form. Do we just believe her because she is Hannah Arendt? Why should we?

2) whenever she says "man" she is talking about a small intellectual elite and seems to think they can represent everyone else. When she says that action has replaced contemplation, etc, etc, she is talking about a few intellectuals that in fact only represent themselves. It is the same sort of bubble problem that afflicted the NY Times, etc, in recent times.

If you are talking about the "human" condition you are obligated to explore all that is human, not just West 67th Street. Others have done this better than she did.