In February we’ll read Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. Here is the schedule:

February 10: Introduction to Le Guin’s life and work

February 17: Chapters 1-3

February 24: Chapters 4-6

March 2: Members-Only Zoom Call, 8PM Eastern

March 3: Chapters 7-9

March 10: Chapters 10-13

March 13: Members-Only Zoom Call, 3PM Eastern

The read-alongs are free. Sometimes I write some extra posts for paid subscribers, and the Zoom calls are exclusively for those who financially support me, but the main read-along posts are available to everyone. I invite you to buy a copy of The Dispossessed and get involved with our discussion.

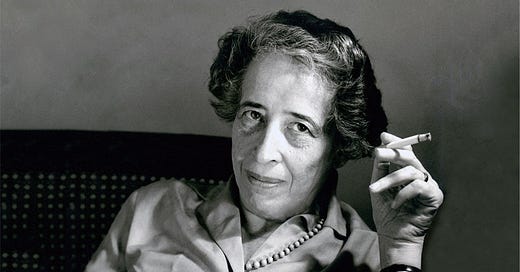

Today marks our penultimate post about Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition. I’ll give my thoughts on the book, including the last half of the final chapter, in just a moment. But I want to invite everyone to leave a comment below about your takeaways from this book – positive and negative – and your overall thoughts. Next week, I’ll feature some of the best comments in order to expand the perspective of the post.

We live in an inverted world. This inversion has come in two parts.

First, we have inverted the life of activity and the life of contemplation. This is a theme that has come up throughout the read-along, to the distress of some of you. As a few people have opined, Arendt seems to care very little for the life of the mind or contemplation. She is focused solely on the life of activity.

The best way to understand this, I think, is to consider two things:

The inversion of the life of activity and life of contemplation has already occurred. Many reasons could be cited (capitalism, the displacement of humanity stemming from modern science, and so on), but the reason may not matter all that much. We all live in the active world. Arendt’s focus on the vita activa may, then, is reflective of the inversion that has taken place on a much grander scale.

Despite the fact that the vita activa has come to dominate the vita contemplativa, the vita activa is under-theorized. Arendt sees herself as doing some new work by offering a theory of the activa life in a way that previous philosophers have neglected to do. And Arendt thinks this has serious implications for other parts of philosophy. In §41, for instance, we are asked to consider how this shift to the active life has changed our views of the intelligibility of the universe and of truth itself; have we been forced to default to a kind of pragmatism?

That’s the first inversion. The second inversion comes within the active life. First, homo faber was victorious. The acts of making and crafting were made equal to the intellectual life, and eventually they came to be seen as superior. Then, labor became dominant. Animal laborans was victorious over homo faber. Instead of acting, we fabricated; then, we labored. This is a reversal of the hierarchy I highlighted two weeks ago:

We have that the animal laborans could be redeemed from its predicament of imprisonment in the ever-recurring cycle of the life process, of being forever subject to the necessity of labor and consumption, only through the mobilization of another human capacity, the capacity for making, fabricating, and producing of homo faber, who as a toolmaker not only eases the pain and trouble of laboring but also erects a world of durability. The redemption of life, which is sustained by labor, is wordliness, which is sustained by fabrication. We saw furthermore that homo faber could be redeemed from his predicament of meaninglessness, the “devaluation of all values,” and the impossibility of finding valid standards in a world determined by the category of means and ends, only through the interrelated faculties of action and speech, which produce meaningful stories as naturally as fabrication produces use objects…From the view point of the animal laborans, it is like a miracle that it is also a being which knows of and inhabits a world; from the viewpoint of homo faber, it is like a miracle, like the revelation of divinity, that meaning should have a place in this world.

This second inversion is more contentious. Arendt’s labor/work/action distinction is, I have concluded, theoretically suspect. Labor and work cannot be so cleanly divided, and so discussing the victory of animal laborans over homo faber feels like a superficial move. (I admit here that some writings in the Marxist tradition – a tradition Arendt criticized in the book – seem to be more insightful, particularly work on the deskilling of labor.) I do appreciate that action, meaning something like human interaction, is deprioritized, but talking about an inversion of this hierarchy seems off. And so, Arendt’s later thoughts on what facilitates this inversion – like her discussion of secularization – don’t appear to be fruitful areas for consideration.

If you disagree, let me know.

And so we come to the end of the book. Unlike our read-along of Nicomachean Ethics, where I felt we were climbing higher and higher throughout the book, each chapter building on the last and giving us a better view of the totality, our read-along of The Human Condition has been a struggle, though not quite a slog.

I am glad I read this book, and I’m glad we read it together. But as I closed the book, I felt that many of Arendt’s insights were scattered, that much of the book was a series of digressions, and that the bulk of the book could be ignored. Some of it was certainly worthwhile, but not the majority of it.

In the corporate world, we complained that a meeting could’ve been an email. I feel that this book could’ve been an essay. It would have been a good one, too.

I did not see it coming at all, the conclusion of The Human Condition. Though the book argues again and again for the importance of action and the public sphere, it nevertheless ends with the following quote from Cato: “Never is he more active than when he does nothing, never is he less alone than when he is by himself.” Why?

Arendt’s central line of reasoning in The Human Condition is clear (even though many details are not): What constitutes the essence of humanity, what makes us different from all other living organisms, is our capacity to act as unique individuals and among other unique individuals. Modern society, however, has brought about the domination of our active life by animal laborans and the decline of the public sphere. As a result, Man “is on the point of developing into that animal species from which, since Darwin, he imagines he has come.” The “future of man” is at stake. So what does Arendt suggest we do? Not much, or a lot; depending on your point of view.

Arendt writes: “In this existentially most important aspect, action, too, has become an experience for the privileged few”. She continues: “Thought, finally . . . is still possible, and no doubt actual, wherever men live under the conditions of political freedom.” In these “dark times,” the only act of resistance is for every one of us to struggle to continue to think. But what does to think mean? To answer this question, Arendt decided to investigate “the life of the mind” as her next philosophical project.

When I was reading the last paragraph of The Human Condition, I was immediately reminded of Theodore Adorno, one of the founding members of the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory. Here’s the famous opening sentence of his book Negative Dialectics: “Philosophy, which once seemed obsolete, lives on because the moment to realize it was missed. The summary judgment that it had merely interpreted the world, that resignation in the face of reality had crippled it in itself, becomes a defeatism of reason after the attempt to change the world miscarried.” In other words, it continues to be important to think. Given the similarities in their training, backgrounds and life circumstances, we should not be surprised by common strains in the thinking of Adorno and Arendt.

There is another common theme between the two that I think we must not overlook. Both believed, when they returned to Germany after the war, that it was dangerous to try to forget the past, to move beyond it, too quickly. Adorno wrote: “One wants to break free of the past . . . wrongly, because the past that one would like to evade is still very much alive. National Socialism lives on” and he considers “the survival of National Socialism within (italicized) democracy to be potentially more menacing than the survival of fascist tendencies against (italicized) democracy.” Adorno’s concepts of Authoritarian Personality and Collective Narcissism are remarkably similar to Arendt’s description of life in modern mass society pervaded by production and consumption.

When I first started reading The Human Condition, I assumed that the book was Arendt’s attempt to find a counter-measure for Totalitarianism. I wasn’t wrong, but my interpretation was too narrow. Like Adorno, Arendt is also alerting us to the totalitarian tendencies already within democratic societies. She is telling us: “Don’t just look for enemies on the outside; look for them within ourselves also.” For me, this is the most important lesson of The Human Condition.

With the benefit of hindsight, I see that Arendt’s career represented a life-long, continuous effort to achieve an understanding (her favorite word) of the ever-evolving human condition and the challenges it presents. Each of her major publications constituted a step in that life-long process. I admire her dedication and determination.

I have wanted to comment but have had difficulty formulating any reasonable coherent thoughts. I have found this to be a difficult read. It’s densely written. I have described it to my wife as Arendt uses ALL the words in her writing. Weeding through that to the salient points has been challenging.

There has been some wise foretelling of the future we currently live in and it’s clear this has come through reasoned contemplation on her part. Funny when she puts so much focus on action.

Each chapter has meandered about and rarely felt like a connected whole. It’s as if she’s gathered a series of intellectual café debates and put them together in one book. I’m glad I’ve read it but I’m left feeling like I may have missed the point(s).