The World Has Dorkified Itself

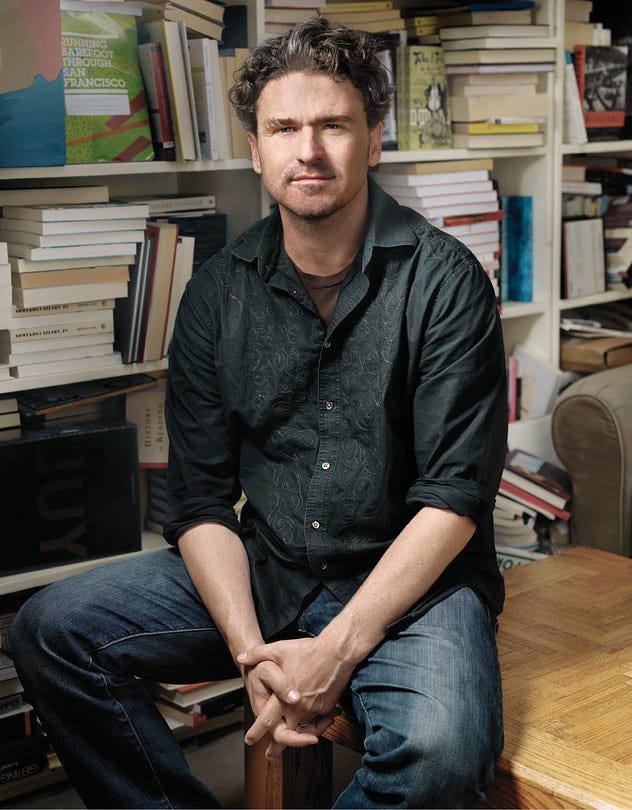

The Circle by Dave Eggers, Part 2

On February 28, I’m taking part in a live event in Austin, TX: KILL THE INTERNET. It’s a night of philosophical discussion.

I’ll be giving a talk called ‘The Dignity of Darkness,’ on the role of privacy in human flourishing.

You can purchase tickets here.

(You can use the code LONESTAR to save 20%)

Welcome back to our 2026 book club on the philosophy of technology. Throughout the year, we’re exploring questions like:

What effect has the rise of digital technologies had on the human condition?

What do we lose – and what do we gain – when we live our lives online?

What do conventional narratives about technology (techno-optimism, techno-pessimism, fatalism) miss? What facts do we need to consider? What alternative narrative about technology do we need to construct?

This February, we’re reading Dave Egger’s The Circle. Here’s the schedule:

February 2: The Circle, up to page 118 (ending at the section that begins ‘In the days that followed, Mae knew it could be true…’)

February 9: The Circle, up to page 234 (ending at the section that begins ‘It was all easy enough to assimilate…’)

February 13: Members-Only Zoom Call, 8PM Eastern

February 16: The Circle, up to page 338 (ending at the section that begins ‘On a granite panel outside the Protagorean Pavilion the building’s namesake was quoted loosely…’)

Optional: ‘The Narcissistic Personality of Our Time’ by Christopher Lasch

February 22: Members-Only Zoom Call, 3 PM Eastern

February 23: The Circle, to the end of the book.

The call on February 22 is for paid subscribers; a recording will be made available to those unable to attend. These calls will include a short presentation and then a group discussion.

Notice that I added a second members-only call on February 13. That’s a Friday evening, and it will be a little different from the monthly book club calls. This will be more informal; I won’t have any material prepared. It’s an opportunity to talk with fellow subscribers, and with me, about the issues we’ve been exploring in this book club. Come with a topic, a question, or just a beverage.

I can’t guarantee two calls every month, but I’ll try to host a second one whenever I can.

A thought struck me as I was thinking back on The Circle this week: at one point, Annie asks Mae for a verbal non-disclosure agreement. After all, she’s about to see something that she shouldn’t even know about. So much for ‘All that happens must be known.’

And of course, Mae feels violated when Francis uses her as an example at a company presentation.

There’s a new app designed to make dating easier, to eliminate the friction of the early stages of courtship. You can use the app and find out everything you need to know about your potential partner: allergies, likes, dislikes, favorite restaurants. Your romantic interest has now been delivered to you via an algorithmically packaged JSON file, rendered on your screen, and made totally legible to you. Now, you can make the perfect first-date suggestion, with none of the worry. Everyone in The Circle is thrilled with the concept – or at least willing to play along during the presentation – but something feels very different when Mae is being talked about on stage.

There’s a strange tension many of us experience when we give out information about ourselves. I write in this newsletter about my experience as a father, for instance, and one of the things this does is build a sense of connection and familiarity with the reader. You know a little bit about me, and hopefully this makes it easier to connect with the ideas that I’m presenting. But now that I’ve given out that information, it is out there in the world — easily searchable, easily catalogued, easily referenced when desired. And this also leads to a sense of alienation from others.

I don’t experience this much myself — I keep a lot of personal details private, and I’m not famous enough to be the center of any so-called ‘discourse.’ But you can see where this goes. As information about you accrues, others can have conversations about you, but with none of the personal intimacy that we normally associate with access to this information. You experience what Mae has experienced: a matrix of preferences (or of stories, factoids, etc.) presented as your essence.

At The Circle, this goes much deeper. Mae is sent to the clinic – all the newbies are supposed to go their first week, so she’s late again – and given the full screening. This includes swallowing a sensor hidden in a smoothie — something that she’s only told after she’s drunk the smoothie. As the clinic’s sign says: To Heal We Must Know. To Know We Must Share.

Mae’s worry, or her sense of being a little unsettled, is quickly gone, though, when she finds out that her parents can join the company’s insurance plan. This is a life-changing, perhaps even life-saving, development. Mae’s father suffers from MS, and his insurance no longer wants to pay for some of his medication. Being on the Circle’s healthplan would solve all of these problems. Annie reminds Mae of a Circle slogan: ‘Anything that makes our Circlers’ lives better instantly becomes possible.’

Mae should have remembered that, Annie said. It was in her very first orientation. In fact, several people are miffed that Mae didn’t disclose this problem sooner.

In this week’s reading, we’re introduced to Mercer. He’s the Luddite of the novel — not someone who completely spurns the digital world, but someone highly skeptical of it. I think it is fair to say that he is Eggers’ stand-in, the voice of reason who keeps on speaking, even if no one will listen.

For instance, he can’t seem to understand why Mae is so enthusiastic about the work done at The Circle. He also hates that Mae constantly posts about him:

‘I can’t send you emails, because you immediately forward them to someone else. I can’t send you a photo, because you post it on your own profile. And meanwhile, your company is scanning all of our messages for information they can monetize. Don’t you think this is insane?’

That is not the only complaint Mercer has. He believes that The Circle does not enable social connection, but rather manufactures a new need that only they can fill: ‘It improves nothing. It’s not nourishing. It’s like snack food.’ Like junk food manufacturers, The Circle creates products that are designed to be addictive, to keep people eating empty calories.

Mercer also gives us a great description of this brave new world: ‘The world has dorkified itself.’

When Mae meets with Dan to discuss her participation rank, it’s hard to see how Mercer is wrong. Mae’s Participation Rank has fallen to 9,101, and she hasn’t been attending enough company parties and events. Dan says, ‘We started worrying that we were somehow driving you away.’ (He doesn’t say who the ‘we’ includes.)

Mae had missed one of those parties because she was getting aloe for her father. The root problem, Dan tells her, is that she didn’t check the company store first. It’s better-stocked, curated, and designed to meet their needs. And while it is ‘very, very cool’ to spend time with her parents, she needs to remember that, ‘we like you a lot, too, and want to know you better.’

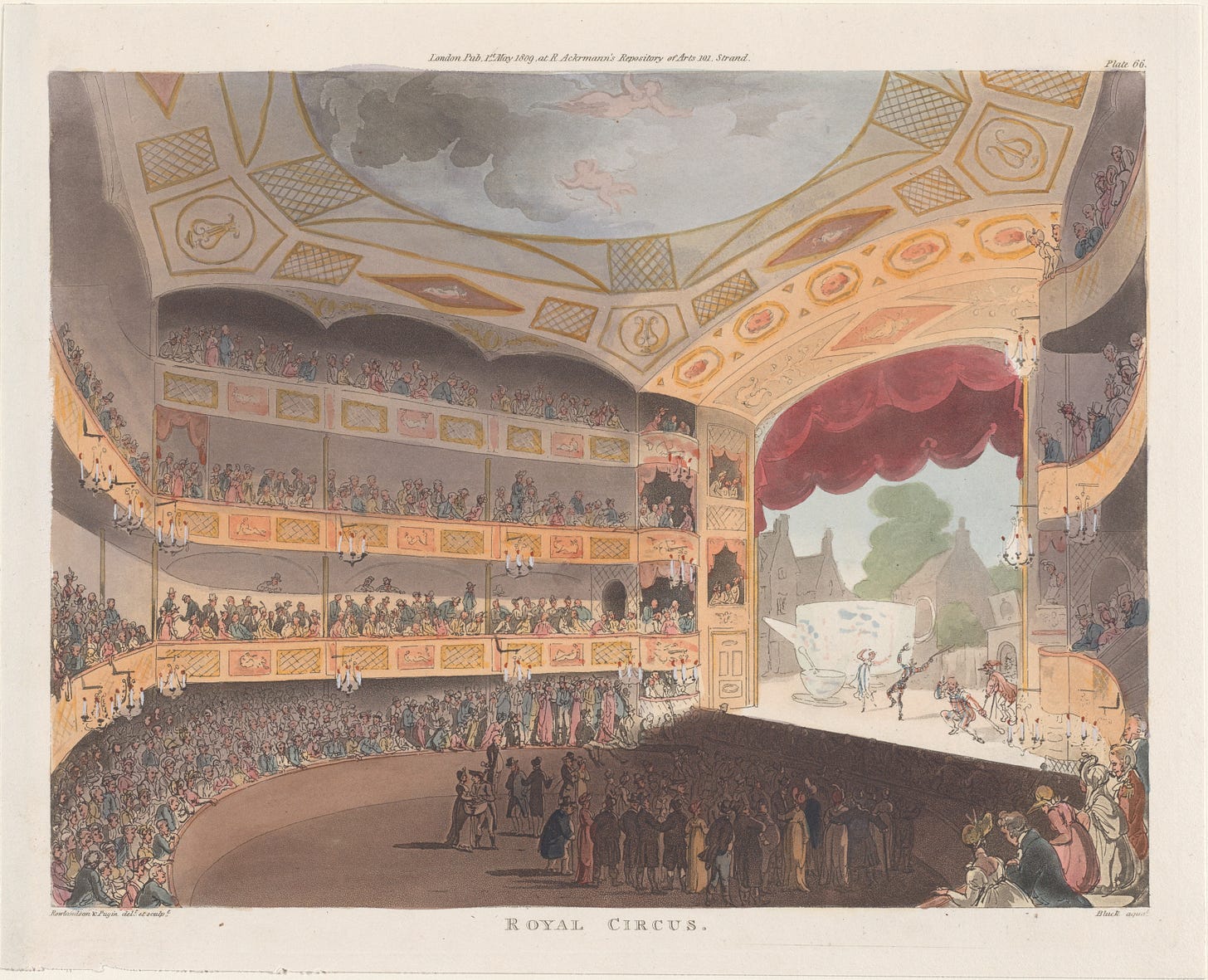

We also see Kalden again. Kalden is surprisingly like Mercer — strange for a Circler, strange enough to raise Annie’s suspicions. Kalden and Mae run into each other at an on-campus circus performance, which Kalden seems to find distasteful: ‘A bunch of court jesters here to entertain royalty.’ Mae’s ‘friends’ at the performance – her coworkers – interact with her through their phones and tablets, sending messages and waving from a distance, but Kalden is different. He comes to Mae directly, interacts with her and the world around her physically. He doesn’t share his last name, and he doesn’t show up when she searches the database of Circlers. He’s different, and that makes Mae curious — and, I think it is safe to say, attracted. That Mae finds Mercer so annoying and Kalden so intriguing is something worth thinking on.

I want to talk a little bit about the tone of the novels. It is heavy-handed and didactic. Eggers has a clear perspective, and some readers think it is a satire that lays it on a bit too thick. The clinic’s signs are one example of that.

I think there is something to this. Sometimes it does cause me to roll my eyes. But this week, I had a realization. I only roll my eyes when Eggers takes the implicit assumptions of the Circle and makes them explicit. The slogans, the odd dialogue. All of that tells rather than shows.

‘Show, don’t tell,’ is one of those stock pieces of writing advice that I think is only good in moderation. Sometimes, we need to be told. I think this is why I can still appreciate The Circle, and can in fact appreciate it more in 2026. Eggers is telling us what the culture at large is thinking.

Recently, I read Amanda Montell’s Cultish, which is a fairly breezy look at what she calls ‘the language of fanaticism.’ It made for an interesting supplement to The Circle, because Montell emphasizes the ways in which language is used as a builder of identity and a means of social control. It allows for the construction of a shared thought-world, where everything can be processed in specific terms (usually designed by the leader). Montell calls the book ‘Cultish’ because she does not think this is limited to cults. CrossFit uses strange jargon as well, and while CrossFitters might be a bit fanatical, it’s hard to call it a cult like, say, the People’s Temple.

The Circle is certainly cultish in Montell’s framing. When Josiah and Denise talk to Mae about her low participation, there’s a careful tuning of the language. Mae wasn’t very present (she uses this a bit metaphorically), and she’s told that the opposite of present is absent. This is used as a way to make her see that, while not mandatory, she really should be attending more events on nights and weekends. And you show that presence through things like zings, comments, blips, blurps — the language of the Circle all runs together to me, so I know some of those aren’t right.

We also see that manufactured social neediness that Mercer described, like when Josiah is hurt and bewildered that Mae doesn’t follow his 143,891-zing-long WNBA feed. She needs to remember PPT: Passion, Participation, and Technology. If she doesn’t she's being ‘sub-social.’

Mae leaves that interaction feeling ashamed of herself. She chides herself: Be a person of some value to the world.

The dynamic being established is constant affirmation of your value and the company’s mission, followed by egular chiding for failing to meet ever-changing, and largely unstated, standards

Which, of course, is a great way to get people to participate more. It might constitute abuse of some kind, but it sure is effective.

We could also discuss the way Mae wants to climb the ranks after her encounter with Josiah and Denise. I don’t want to repeat myself, so I’d encourage you to look at this review I wrote of C. Thi Nguyen’s The Score on the concept of value capture:

Without going into too much detail, we see the value capture that Nguyen describes when Mae begins to obsess over every number and metric. There’s a paragraph (beginning at 194 in my edition) that is over two pages long, where Mae understands everything around her in terms of metrics. Even her sexual encounter with Francis is viewed through the lens of metrics, and Mae relishes in the feeling of power it gives her.

But Francis exercises his own power over Mae by recording everything — and at the Circle, nothing gets deleted.

Here are some of my favorite comments from last week.

From Miguel:

Oh man, I know the novel is about more than big tech, but the world-changing mission, the futuristic campus (not office, of course), the charismatic leaders… Having lived close to that world, it feels uncanny.

I noticed a contrast between the reality of the Circle and Mae’s life outside of work. I believe the scenes with her parents or alone in nature are there for a reason, maybe to remind us about what’s missing in a world of total surveillance?

Finally, I’m interested in the ideology of the Circle (and this applies beyond the novel). Surveillance is justified in the name of safety and justice—noble goals, like Jared said. To what extent do the employees genuinely believe in this vision? The ones we meet seem like true believers. Is that really so? Or are they deluded into it? Maybe, being surveilled, measured and tracked all the time leaves them no room to voice any doubts.

Miguel’s observations would also apply to this week’s reading, such as when Santos decides to ‘follow [Stewart’s] path of illumination’ and ‘go transparent’ by broadcasting her entire life. Transparency is being used in pursuit of a noble goal – fighting corruption – but something feels off. It’s a little convenient that Willamson, the senator who wants to enforce antitrust law, has been found keeping secrets, while Santos (who hugs on the Three Wise Men before making her announcement) will embrace transparency while also being cozy with the Circle.

From Adam:

The reason the Circlers seem so strange is because they act IRL the same way people act online. The constant misunderstanding of tone and context reminds me of the way someone can imagine an entirely different intent to your text comment. Annie’s sudden spiral of paranoia when Mae doesn’t respond to her immediately, or the Portugal brunch guy’s assumption that Mae’s failure to RSVP is intended as a personal sleight also remind me of the ways online interactions go wrong.

The satire in this book seems pretty crude. It may seem like everybody behaves this way online, but 90% of posts on social media come from 10% of the users, while the overwhelming majority of people who rarely/never post fade into the scenery. I admit I may not know what I’m talking about -- I’m a life-long late adopter who has skipped a lot of tech crazes and quit most of the others. I know that satire needs to exaggerate, but if it exaggerates in the wrong way it kills the relevance. It’s difficult to believe, even in a cult-like tech company, even at the height of tech optimism a decade ago, there wouldn’t be a backlash to the panopticon the Circle is creating. Yet apparently no one is bothered by the end of privacy, not just in the company but in the entire world of the novel. Even in a satire, that’s tough to accept.

I think that in this week’s reading, we get more insight into the satire. As I wrote in response to Adam, I think that Mae is a true believer at this point. She has bought into the Circle’s mission, so she isn’t thinking about its flaws. I was asked as a follow-up about why Mae is a true believer. Here’s my response: because the Circle is very cool. Mercer might say that the world has been ‘dorkified,’ but at the time – remember when Eggers wrote this – we were still in an era of loving Big Tech and all it provided. Mae has an exciting new job, and now she has a job that keeps her father alive, so she’s highly motivated to be a true believer. Add to that the psychological games the Circle plays, and I think we have our explanation.

It's a small thing, but the direction to 'go to the company store' really struck me. My dad grew up in a mining town. Late 19th and early 20th century, the miner's HATED the company store. It was a symbol of how the company controlled way too much of your life. Debts at the company store tied you more tightly to the company. So did the fact that most miner's lived in company housing. The Circle has both, pitched as ways to help the Circlers, but clearly a way to further dependency.

As part of a long, bitter strike in the 1920s, every company store near where my dad grew up was vandalized or burned to the ground after some rioting. One miner was killed, and 100 years later William Davis Memorial Day is still celebrated in former mining towns across the region. The stores and housing were 100% a means of control and the workers and company both new it.

The dawning response I had reading Mae’s interactions with the Circle was that she had joined a cult. This was predominant in the scene where she was castigated for not attending the Portugal interest group. Their demands and her responses were so stilted and inauthentic. But this doesn’t help me appreciate the book because I don’t understand how Mae is inducted into the cult so quickly, or how this Circle cult has been so successful in dominating the tech industry with a product I feel nobody really wants (TruYou: the enforcement of real name interactions on line) and the main selling point seems to be if you engage in a wildly unrealistically seeming amount of online discourse (which isn’t qualitative? Just the quantity seems to be enough?) can make you go up a leaderboard and get prestige? I feel like this has been tried and doesn’t work.

The one grounded person, Mercer, provides maybe the best insight/justification for the satirical unreality of the Circleers which is that their speech is arrested at Junior High, which is where digital life for many youth begins and maybe that's why the maturity of the very young employee base might have even been influenced by the Circle (which is 6 years old, if I recall correctly but it doesn’t quite push them back to junior high age).

But I just feel like very stupid people have to exist for the plot so far to even work. I appreciated Jared Henderson's point that he seemed to see realism in the 2013 tech world he was in, but I haven’t seen it so it just seems crazy. The idea that idealism of building something world-transformative (that makes you a ton of money and power) drives many in tech can explain some of the cultishness of the Circle crew. But it still nags at me

Kaldan is the interesting character for me, and also makes me question what Eggers is really doing. I want him to be a supernatural injection into the narrative, maybe a real spiritual evil force of some kind that lies behind or manifests in this (Infernal?) Circle with its underworld Big Red Box (I think I have that figured out already in advance of any big reveal to come in the future sections) That would be interesting. He plucks fruit for Mae, maybe like a symbolic serpent in the garden.

One thought I had about the both junior high level of the discourse and the stilted cultishness of the discourse is this might be a 1984/Brave New World riff, where Newspeak has to replace normal discourse because other words for what’s going on are too fraught for the cult. Transparency, participation, etc. have sinister meanings as the story unfolds. And the total surveillance or “sousveilance” (the Circles are doing it to themselves, but coercively) resonates with 1984 and BNWs “everyone belongs to everyone else” and nothing should be secret. Interestingly we are told later that you can have your camera off in the restroom, which is were Kaldan has sex with Mae (eww, also: he climbed over the tops of several stalls to get to her? He seems more like a demonic alien entity to be that lithe)

Harbor seals and Houseboaters are an interesting contrast to it all: they drift from each other, are challenging to approach, and have below-the-surface lives that can’t be seen

I will think I need a real explanation of why Mae is so oblivious first to the boundary crossing of the various men (and women!) in sexual banter in a corporate environment where the joke is normally that HR/Metoo has ended any such sexual banter but maybe it’s just that Metoo wasnt big until 2017 after the Circle was published?

and here I am, making a "First Post" and waiting with bated breath to see if I get likes. Maybe I'm being overly critical of Eggers, .... but I'm choosing this for myself.... Zing!