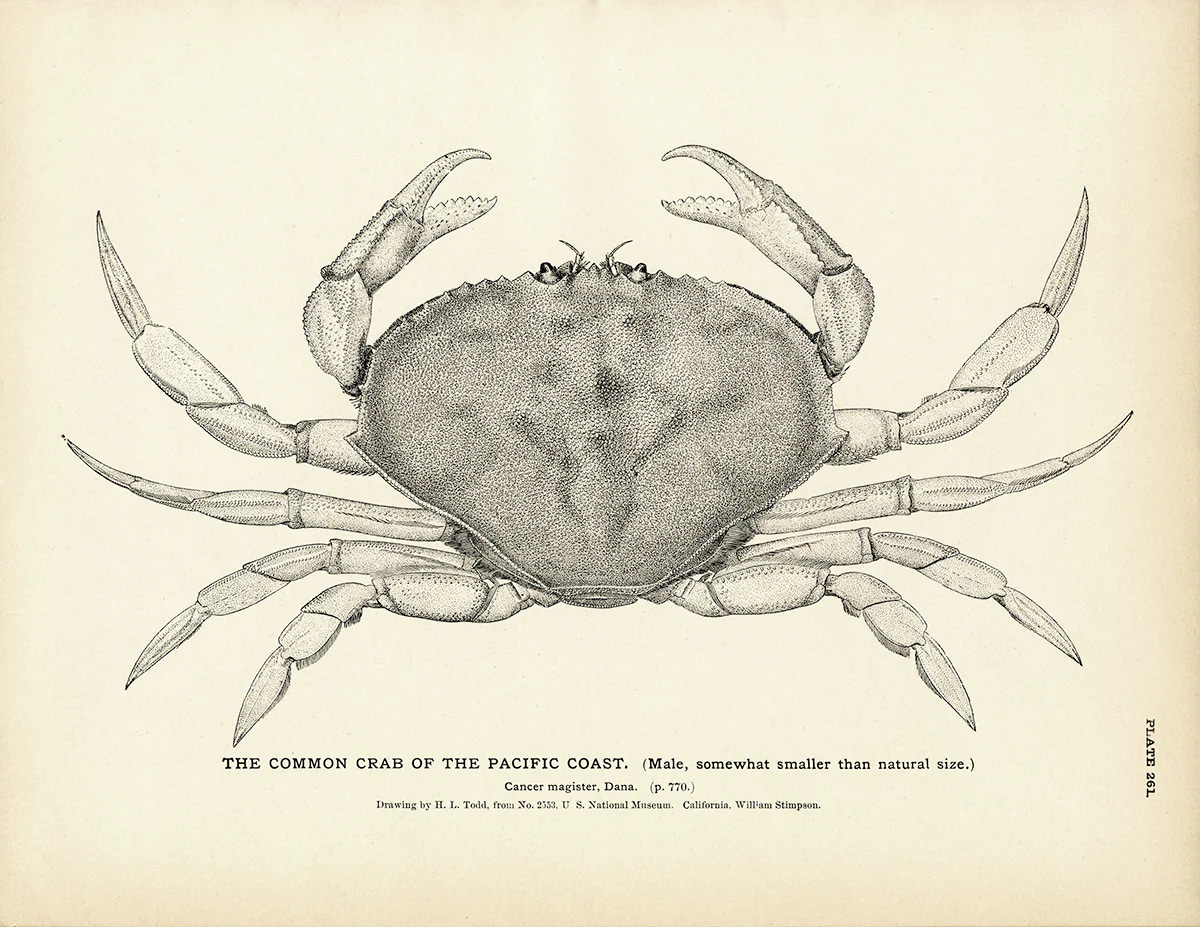

Thinking about the immortality of the crab

Plato, poetry, philosophers in wells, Dante's creative liberties, and, above all, the crab.

I had intended today’s entry to be the second installment of Writing Advice from C.S. Lewis. But then I had some thoughts, and I started writing, and I thought Clive could wait for another week.

The Spanish have a lovely idiom, Pensando en la inmortalidad del cangrejo, which translates to ‘Thinking about the immortality of the crab.’ A schoolgirl, caught staring out the window by her teacher, might use this line when asked what it is that she is doing. It’s a way of saying that you have been daydreaming, letting your mind wander, perhaps pondering the little things. You have been thinking about the immortality of the crab.

The Wikipedia article for the idiom is longer than you would expect. Instead of simply explaining the meaning and some common variants, the article also chose to highlight a novel inspired by the idiom and several poems, like this one by Miguel de Unamuno:

The deepest problem:

of the immortality of the crab,

is that a soul it has,

a little soul in fact ...

That if the crab dies

entirely in its totality

with it we all die

for all of eternity

Idioms are a strange beast. Our common idioms – for most readers of this newsletter, English idioms – are as good as dead. They have their literal and non-literal meanings; the non-literal meanings are readily available to us, but we never really think about their literal meanings. Yet their literal meanings, which are often strictly false, are the most illuminating.

I imagine most Spanish speakers don’t take much time to think about the literal meaning of this idiom. You just say it, and when someone says it is just something that was said. There is no need, and probably not too much of a desire, to think too deeply about what it really means.

Yet that is what the poets decided to do. It is also what the philosophers should be doing.

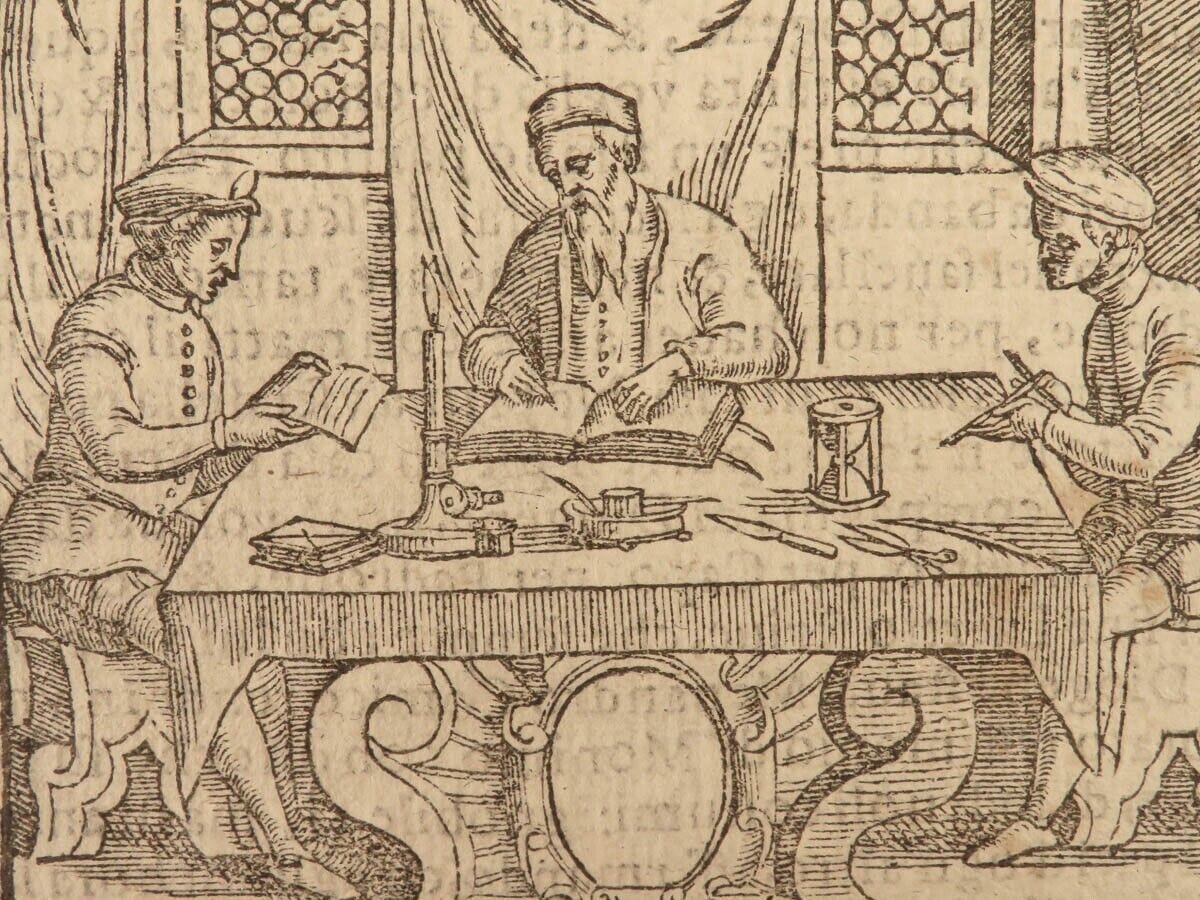

Plato was no lover of poetry or poets. The final book of the Republic is essentially an attack of poetry. This has been joked about extensively over the years, but little popular discussion takes into account any of the peculiar historical factors which would influence the philosopher’s assessment.

For one, poetry in the ancient world was not the sort of thing that one read contemplatively or silently. Homer, the greatest of the Greek poets, was called the educator of Greece in the Republic, and Plato agrees with the assessment. Homer’s work was often publicly recited for all to hear. It was a kind of public liturgy, of educational, spiritual, and moral value. Understood this way, it is not so different than the work done by Socrates in the city. Philosophical inquiry was public, including conversations, demonstrations, and debates. This too was a kind of public liturgy, though perhaps not as captivating as a recitation of Homer, with similar ends in mind. Philosophy and poetry were in some kind of competition with one another.

This competition was more severe than we might have expected. Meletus, the prosecutor of Socrates in the Apology, is said to be a representative of the poets (in addition to others). As Socrates was charged with corrupting the youth and with impiety toward the gods, it was in part the poets calling for his blood.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Commonplace Philosophy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.