We should be grateful for all those bad books

The economy of publishing and a bit of silver lining

It’s quite fashionable to talk about the horrible state of publishing. Publishing is killing literary fiction, we say, or publishing has abandoned men. Some of these criticisms are based in fact – though I suspect most are based on vibes and rough approximations of what’s going on – and sorting through them isn’t the point of this piece. I want to focus on the biggest, most pervasive criticism of the publishing industry and argue that it is, in fact, a virtue.

Big publishers publish too many bad books, the critics say, to which I reply: That’s great.

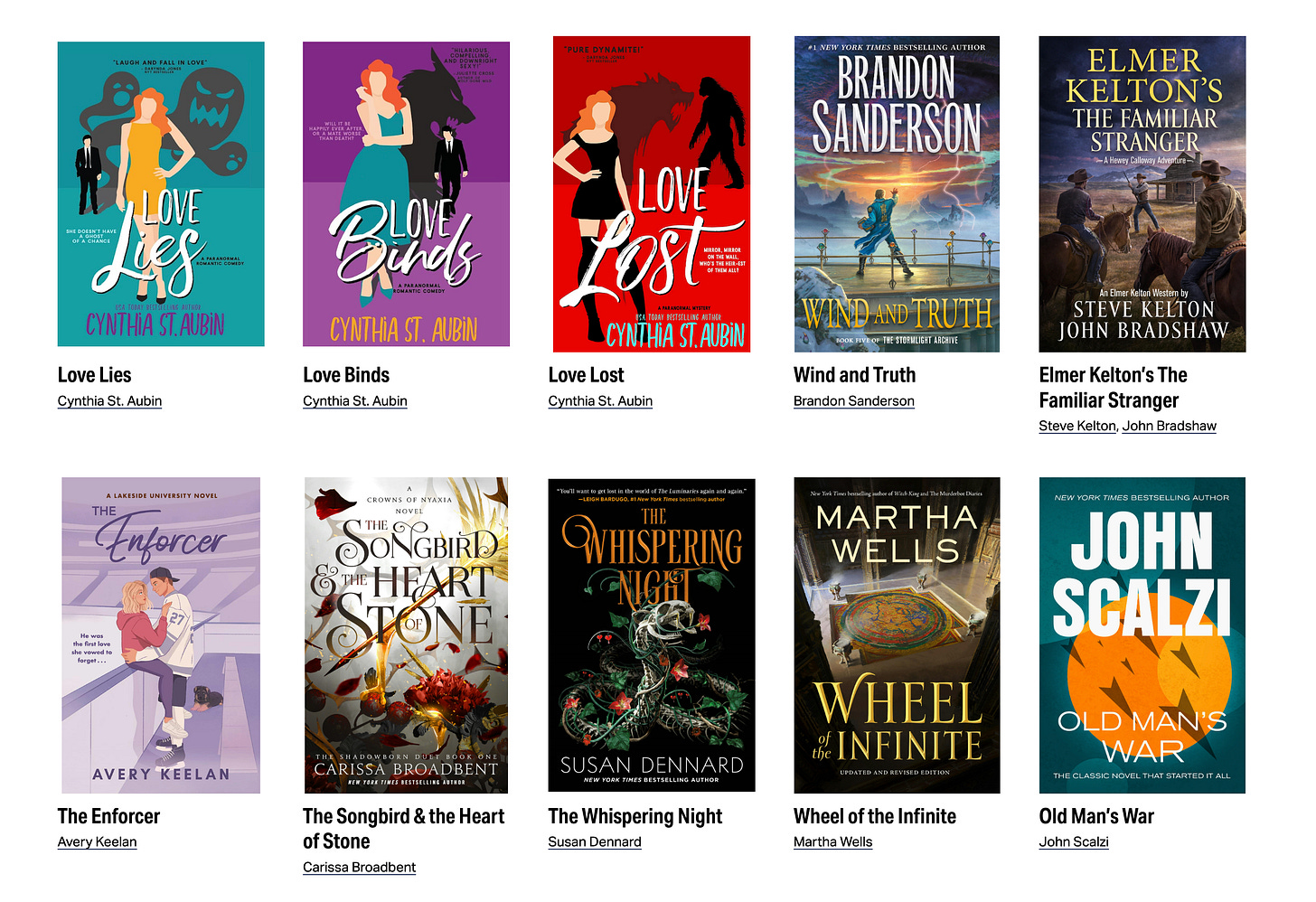

To illustrate the point, let’s look at one publisher’s new releases page. Since I am a fantasy and science fiction fan (among other things), let’s look at Tor.

Looking at these images, I see one – perhaps two – titles that I’m interested in. I have said before, publicly, that I don’t understand the Murderbot hype, I have really soured on Brandson Sanderson (and didn’t bother to read past the first part of Wind and Truth, which in my defense meant I still read about 200 turgid pages), I don’t like John Scalzi (I don’t think he’s funny!), and I have no interest in what I believe are the ‘romantasy’ titles on this list.

I’m generalizing here, and so I could be wrong on the particulars, but I’d say that 1 or 2 of those books has a chance of being good, at least by my lights; quite a bit of those books are going to be bad.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth, though. Murderbot books sell fabulously well — so well that Apple TV thought the IP was marketable enough for an adaptation. Sanderson’s novels are guaranteed bestsellers. Scalzi’s books (I’m guessing, here) are probably reliable base hits, though maybe not home runs, for Tor. And those romantasy titles? You may not recognize the covers, titles, or authors, but they’re probably selling a lot better than many of your favorite authors.

The good books – here I’ll ask that you just assume with me that the books I like are the good books – don’t sell nearly as well. This isn’t a case that is unique to Tor, either. I suspect that you could say something similar about most publishing houses.

The bad books sell better than the good books.

As I see it, there are two potential morals to this little story:

Publishing, and the reading public, is deeply flawed. We ought to educate readers so that they will read better books.

Good books and the authors writing them are essentially parasitic on the publishing industry; the same could be said for the readers of these books. The revenue they generate would not support a publishing house — and in fact, the revenue they generate would not even support their own self-publishing efforts.

That first moral is the one we’re all tempted to latch on to, and there is something to it. For a variety of reasons, people want easy reads. Because of this, books that challenge conventions, experiment with form, or demand something of the reader aren’t often successful. So, we argue that we need to encourage people to read the good stuff. We need to teach them. We need to save literature. (For some readers, that would mean ignoring anything offered from Tor and other genre publishers, but that’s a debate for another day.)

If we don’t do this work, we might be giving in to what the critic

This is what philistinism looks like: the refusal to differentiate; the elevation above all else of the impulse to celebrate; the cordial enjoyment of an artist’s beliefs rather than their thought processes.

So, I do want to grant the point. We have to keep fighting the good fight.

And yet, there is more to the story. The simple fact is that the books I and many of my fellow snobs embrace, especially in contemporary publishing, wouldn’t be published at all if it weren’t for these bad books. (This is why I say we’re essentially parasitic on publishing.) It is an uncomfortable fact, but one that we have to come to grips with.

This has all been very quick, so let’s look at how publishing works — and I might as well tell you how it has worked for me (so far).

If you want to publish a book at a major press – the sort that critics have contacts with, and the only sort that gives you a half-decent chance of getting noticed – you will typically find yourself a literary agent. You send them a query letter and either a proposal or a manuscript; in the case of nonfiction, its nearly always a proposal, but for fiction manuscripts are expected. If an agent likes you enough to talk to you, you’ll start having some conversations. Eventually, one of them will ask if you want to work together.

I queried 15 agents and had phone or video chats with three. That’s a fairly high hit-rate, but I expect it is partly due to my YouTube following — when I was querying, I had about 250,000 subscribers, and now I have about 420,000. But even with a large following, you have to convince an agent that the book is good and salable. All three agents I spoke to had reservations about my initial project, and all offered to help me refine it to greater or lesser degrees. I eventually started working my agent, Daniel, and we revised the proposal from top to bottom. He was very helpful throughout the whole process.

The reason we do this is because we need to convince someone else – editors at publishing houses – that the book is going to be good and a hit. That’s the winning combination: it should be good and it should sell a lot of copies. But I suspect that if they had to choose between good and sell a lot of copies, economic necessity would force their hand.

Based on that calculation, an editor (or hopefully, a few editors!) will make you an offer on the book and give you an advance. (I can’t speak about any of this, because Daniel and I aren’t quite done with my proposal — but I think I’ll be in the submission phase soon.) Your agent is the one responsible for negotiations. That’s how they earn their 15% cut of your advance.

Publisher’s Lunch, a great (paid) resource for industry news, doesn’t usually give specific figures for deals; there’s some discretion in the industry. But they do use some phrases to describe deals, letting you ballpark the value of the contract.

Nice deal: $1 to $49,000

Very nice deal: $50,000 to $99,000

Good deal: $100,000 to $250,000

Significant deal: $251,000 to $499,000

Major deal: $500,000 and up

(You’ll notice there are gaps in this, like for a deal that it $99,500. I expect those aren’t common and that the industry prefers round numbers, but that’s just my speculation.)

So as you can see, there is some potentially serious money to be made. (At least in nonfiction; my understanding is fiction advances are lower.) Your agent will get 15% for his or her efforts working with you on your proposal, advising you, and negotiating; I think that this is a pretty good deal, all things considered.

Already, I think you can see how the industry works, though. Your agent takes you on as a client because he thinks that 15% will be worthwhile (or you’re a real passion project, but there can only be so many of those.) He’s making a bet on your future success. I think it is fair to say that editors are thinking in similar terms. That advance is a bet. Everyone is making a bet. Publishing is sports betting for people who wear thick-rimmed glasses.

But here is the dirty secret: no one buys books.

Or, sort of. I think that the better summary of the article above is that most books don’t sell nearly any copies, but that the industry is propped up by the massive hits

The CEO of Hachette described it like this:

We’re very hit driven. When a book is successful, it can be wildly successful. There are books that sell millions and millions of copies, and those are financial gushes for the publishers of that book, sometimes for years to come… A gusher is once in a decade or something.

These gushers financially support the publishing houses, drive people into bookstores, and generally keep the industry afloat. These gushers are what makes publishing possible.

After the gushers, you have your midlisters. These people will sell reliably, but they won’t sell fabulously well. (I don’t know the sales numbers, but I would speculate that Brandon Sanderson is a gusher for Tor, while Martha Wells is a reliable midlister — or something better than that, but not really a gusher.) I imagine these books are reliable sources of income for publishers, but they might not do more than keep the lights on.

Then you have everything else. These are the books that simply don’t sell. Especially in fiction, this is where I think many of the gems are. These are the weird, experimental, bold books; these are the books that are worth talking about for years to come. But they don’t sell; many of them don’t make enough money to support the author and the cost of doing business.

For now, publishing functions in a way that lets editors take risks. Because the gushers are so big, money can go toward riskier bets: small authors, authors without big YouTube channels, weird novels. And that’s a good thing! We should celebrate it! These publishers could choose to stop taking these risks, becoming the Stephen King and Stephanie Meyer Publishing Emporium. But for now, at least, the money is spread around, and many writers get their chance to write a work. It helps, then, to remember that for every daring, bold literary debut that gets published, the excess profits from about 10,000 Colleen Hoover novels paid for the editorial and design work.

This is an optimistic essay — I want to assure you of that. It has become standard to bemoan the state of publishing, to talk about the parochial dispositions of editors and the slop that they publish. Yet, we have to understand that we exist in a literary ecosystem. The success of the bad books – the books we snobs love to hate – is what keeps that ecosystem alive.

I think people forget that you can enjoy multiple types. I will read the shittest romantasy I can find, yet I'll also read classics and books on philosophy and the environment. When you watch films, you don't make everything you watch a 4 hour director's cut or complex documentaries, sometimes you watch a sitcom. This is how i like to view it. :)

It's probably just the Pareto principle at work. McDonald's is one of the biggest restaurants in the world, not exactly gourmet food. Every industry has its McDonald's.