A note from Jared: My friend Philip, a professor of political science, recently taught a class on the philosophy of technology. I asked him if he wanted to share any of that class’s insights with readers of Commonplace Philosophy. He sent me this piece on the philosophy of Werner Heisenberg. He touches on science, technology, education, and Greek philosophy. Enjoy.

My intellectual journey is attributable almost entirely to a small set of professors and the books they made me read. I came into graduate school certain I wanted to study something relating to technology largely because of a short unit in my Modern and Contemporary Political Thought class my junior year of college. In this section focused on technology and politics, we read Heidegger’s classic essay “The Question Concerning Technology,” which mystified me and proved impenetrable without serious aid. We then read essays by George Parkin Grant, who drew on Heidegger and likewise profoundly shaped my own thought going forward.

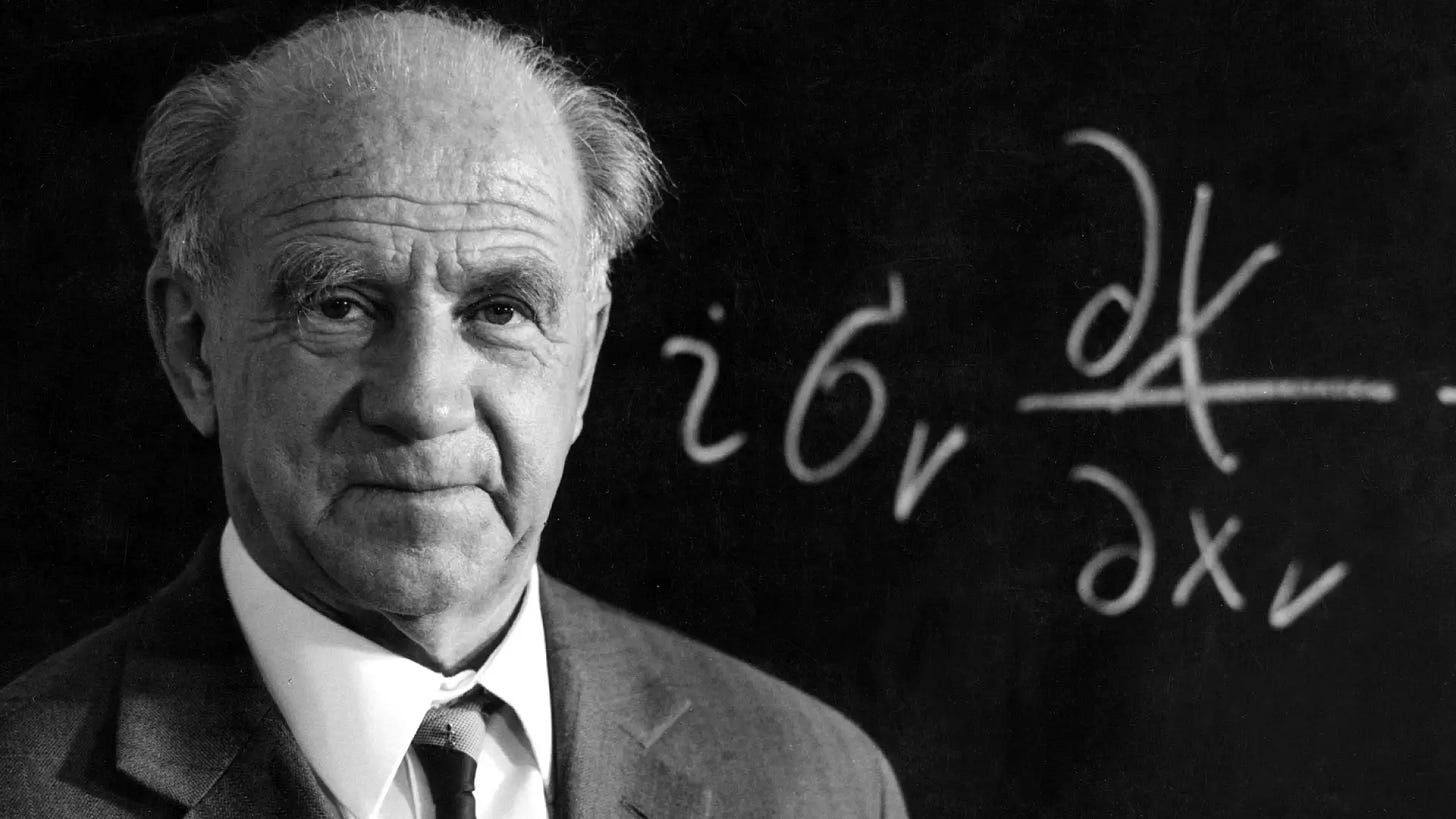

But we went on from there to read the works of someone both Heidegger and Grant were citing, someone who makes regular appearances in the pages of other intellectual greats such as Hannah Arendt, someone whose name might be familiar to many but ideas less well-known: Werner Heisenberg. Throughout his writing, particularly in his book The Physicist’s Conception of Nature, Heisenberg proves insightful, first for his general approach to education in the classical mode, and second for his unique insight into modern man’s relationship to science and technology. I will treat both in turn.

Classical Education

Heisenberg was born to educated, academic parents and raised in Lutheran Christianity. His father was a teacher of ancient languages, and Heisenberg credits his father in various places for inspiring an early interest in what we now call “the classics.” Because of this, Heisenberg was exposed to an above-average amount of classical material for one with scientific aspirations, and his deep reading of Greek philosophy throughout his life left an indelible mark on all of his writing. You can scarcely pick up any work of Heisenberg’s without finding reference to either Plato or the pre-Socratic philosophers.

In crafting his famous lectures on Physics and Philosophy, for example, Heisenberg devoted an entire lecture to the history of “atomism” in philosophy, particularly in pre-Socratic thought. Though he denies that these philosophers can be cleanly equated to our modern scientific discoveries, due to the “empiristic attitude of modern science,” he nevertheless affirms that “some statements of ancient philosophy are rather near to those of modern science.” This is particularly true of Heraclitus; in reasoning that the basic element of the universe was fire, constantly in flux, he was conceptually “extremely near” the advancements of quantum physics. “If we replace the word ‘fire’ by the word ‘energy’ we can almost repeat his statements word for word from our modern point of view,” Heisenberg claims.

It would be stunning to hear a modern university lecturer in the hard sciences even mention the pre-Socratics in a lecture, much less to devote a lecture delivered to a packed house exclusively to their thought. These philosophers are surely outmoded and outdated, one might think, unworthy of serious consideration by someone educated in the modern approach to philosophy and science.

In fact, in his Physicist’s Conception of Nature, Heisenberg argues quite the opposite: that the classical and Christian approach to education remains valuable to us because of its way of asking questions about the world. The classical way of asking questions, Heisenberg argues, drives us more and more towards the truth. The proof is, as it were, in the cultural and intellectual pudding. The classical and Christian approach to question-asking leads to serious philosophical inquiry with obvious results.

In the west, Heisenberg argues, “our whole cultural life, our actions, our thoughts and our feelings, are steeped in the spiritual roots of the West, i.e. in that attitude of mind which in ancient times was initiated by Greek art, Greek poetry, and Greek philosophy.” The characteristic feature of this tradition is not some specific moral principle or some race-based inheritance, as some might claim.

Rather, “What always distinguished Greek thought from that of all other peoples was its ability to change the questions it asked into questions of principle and thus to arrive at new points of view, bringing order into the colorful kaleidoscope of experience and making it accessible to human thought.” The importance of a “classical” education lies in precisely encountering and learning to practice this method of asking questions of principle, questions that aim higher than the material, questions that are ultimately “spiritual” rather than solely “material.” In sum, he argues, “At the root of all Western culture there is this close connection between our way of posing questions of principle and our actions; this we owe to the Greeks.”

Heisenberg’s Insight into Science and Technology

Because of his deeply humanistic background, and because of the constant attention he gives to the philosophical dimensions of scientific inquiry, Heisenberg may avoid the trap into which many scientists fall of being less-than-adequate commentators on broader political or social issues. In his Technological Society, Jacques Ellul spares no ire for scientists in his concluding chapter “A Look at the Future.” He writes that, on the basis of the drivel they spew when asked serious questions, “We are forced to conclude that our scientists are incapable of any but the emptiest platitudes when they stray from their specialties. It makes one think back on the collection of mediocrities accumulated by Einstein when he spoke of God, the state, peace, and the meaning of life. It is clear that Einstein, extraordinary mathematical genius that he was, was no Pascal; he knew nothing of political or human reality, or, in fact, anything at all outside his mathematical reach.”

While Ellul may perhaps be right about his targets (Einstein and Oppenheimer, primarily), and while we might think of ready examples of scientists today who commit the same errors, I would contend that Heisenberg rises above the rest. Here I want to highlight two analogies he develops in thinking about technology and the role of the researcher that have proven helpful for me in my own questioning concerning technology: The first, the analogy of the captain and the ship. The second, the analogy of the arrow and the bow.

The Captain and the Ship

The first comes from his essay “Nature in Contemporary Physics.” One of the disorienting facts of modern science, Heisenberg says, is that the “new” physics, quantum physics, teaches us counter-intuitive things about the world that may contradict our own direct experience. This change is seen in the progress of technology itself: in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, “there was developed a technology which rested on the exploitation of mechanical processes. Often machines did nothing but imitate the actions of our hands,” just in more precise ways and with greater force.

“A decisive change in the nature of technology,” Heisenberg argues, “did come about with the development of electro-technics… There was no longer a direct connection with the old handicrafts, since natural forces hardly known to man from his immediate experience of nature were being exploited.” When we harnessed the forces of atomic and subatomic particles to power our machines, something “uncanny” and “incomprehensible” developed. “Atomic technology” as a culmination of this new era “is exclusively concerned with the exploitation of natural forces to which there is no entry at all from the world of natural experience.”

This technological development mirrors the development of the new physics. Put simply, new advances in physics teach us that our experiments on nature should not be thought of as neutral observers collecting objective information about an external world. Instead, we now know that our observation of phenomena influences that phenomena. “Thus,” Heisenberg summarizes, “even in science the object of research is no longer nature itself, but man’s investigation of nature. Here again, man confronts himself alone.” That is, “the new mathematical formulae no longer describe nature itself but our knowledge of nature. We have had to forego the description of nature which for centuries was considered the obvious aim of all exact sciences.”

The disorienting conclusions this leads one to are, for Heisenberg, obvious. Where before, a scientist could look to the material world for some kind of objectivity, some facts, something on which to ground knowledge through empirical study, now man everywhere “confronts himself alone,” a dreadful prospect for some. This disorienting knowledge has occurred alongside a dramatic increase in man’s power unlocked through the same discoveries. That is, at the same time physicists concluded that “reality” was quite different from what our senses would suggest, they also gained access to the dramatic extension of power of various kinds through harnessing that new knowledge (the applications of atomic energy being the readiest example of this).

Being thus freed from the older science, and existing in the modern world characterized often by a rejection of older forms of custom, morality, and so on, man is liable to feel unmoored. In the aphorism immediately prior to the famous Parable of the Madman, Friedrich Nietzsche says that we find ourselves “In the horizon of the infinite— We have left the land and have embarked. We have burned our bridges behind us- indeed, we have gone farther and destroyed the land behind us.”

Heisenberg develops a consonant analogy, specifically with reference to technology: “In what appears to be its unlimited development of material powers, humanity finds itself in the position of a captain whose ship has been built so strongly of steel and iron that the magnetic needle of its compass no longer responds to anything but the iron structures of the ship; it no longer points north. The ship can no longer be steered to reach any goal, but will go round in circles, a victim of wind and currents.”

In our new technological era, we find ourselves without any clear guide, or perhaps with guides that are suited to prior ages and prior forms of technology but are helpless in the face of the new. However, all hope is not lost. Instead, if the captain can recognize the danger, assess correctly that the navigation instrument has failed, then he could “use a modern compass which is not affected by the iron of the ship, or, as in olden times, he may use the stars as his guides.”

Heisenberg suggests here that whatever tools we had to deal with new technologies in the past are helpless in the face of our rapid technological change. If we hope to sail true, to seek north, to preserve human happiness in the midst of these changes, we must find new guides. We can, perhaps, develop modern guides to living, analogous to the modern compass. We could also, he suggests, look to the stars, seek higher, older, more permanent guides as we chart a path ahead. The analogy thus calls us to do two things as modern people encountering new technology: recognize the danger and seek helpful guidance.

The Bow and the Arrow

Where might we find this guidance? Classically educated and Christian as he is, Heisenberg seems to suggest that we can “as in the olden times” seek higher, spiritual things. In his essay on classical education, Heisenberg recounts a debate that took place while he was at school during a revolution in Munich. In the midst of a discussion about the proper use of force, one student argues that nothing “spiritual” can resolve conflict, only force and action.

Against this, a theology student (with whom Heisenberg seems to agree) argues that deciding who is friend and who is foe even in the midst of an armed conflict, and what should be done to them on that basis, is a “purely spiritual decision.” Heisenberg agrees and adds: “Once the arrow has left the bow, it flies on its path, and only a stronger force can divert it; but its original direction was determined by him who aimed, and without the presence of a spiritual being with an aim it would never have been able to start on its flight. In this regard we could do far worse than teach our youth not to rate spiritual values too low.”

In other words, our actions in the world, both actions in combat and actions of technological creation, are acts taken by spiritual, or “moral,” beings. These beings make choices, and they make them on the basis of certain values, which they in turn learn from their education. We ought, he tells us, to think of our choices and their consequences as morally directional, and more that our education is preparing a host of bow-firers who will make decisions about their aim on the basis of what they learn. Taken together, the analogy of the ship and the analogy of the bow would have us develop proper guides to human life, including the use of technology, through means of the spiritual inquiry encouraged in a “classical” education, which we would then employ both in our vocations and in our personal or private use of technology.

Conclusion

Heisenberg provides the resources to think quite deeply about our modern technological project, allowing us to approach new advancements without nostalgic disdain but with our eyes wide open to the true novelty of our situation. His writing is prolific, and The Physicist’s Conception of Nature only scratches the surface. However, among a host of scientists like those whom Ellul criticizes, Heisenberg seems to me to bring special insight that can help both layman and specialist alike in our wrestling with our new technological age. I hope, like my professors did for me, to introduce students to helpful technological guides such as Heisenberg so that they might go about their own process of developing or discovering tools of guidance in their own lives and minds.

Philip D. Bunn is an Assistant Professor of Political Science in at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, Georgia. His reviews and essays have appeared in Comment Magazine, The University Bookman, and Plough Quarterly, among others, and he writes on Substack at

Thanks so much for sharing, Jared! It's an honor to contribute, and I'm always excited about a chance to get people reading Heisenberg.

Pre-WWII, Heisenberg was one of several scientists involved in quantum physics, from Curie, Einstein, Bohr, Planck etc. While I don’t dispute this article, Heisenberg philosophy included not leaving Germany even though he ( and Planck ) knew of the barbarism of the Third Reich. I know Heisenberg may have chosen not to join the Nazis, but let’s face it, he didn’t leave Germany either and wanted to support as a nationalist their war effort. It’s well known that when the German scientists learned (while imprisoned by the Allies in France) that the Allies had dropped the A bomb on Hiroshima, these well educated German scientists were shocked that they were beaten by the Allies scientists (Manhattan Project) and the Germans cried….The Nazis had lost the war. Based on these actions, Was Heisenberg an ethical scientist/ human being? The author might have an answer.