I was in graduate school when I first read Ursula K. Le Guin. I was coming out of a very long reading drought, a prolonged spell in which I hardly read any fiction for fun. If I was reading, it was articles and books relevant to coursework or my own research.

I can’t say that Le Guin was the one author who reignited my love for reading fiction, but she was certainly a spark, if not the supplier of a good deal of kindling. Dostoevsky provided some tinder, as did Terry Pratchett, Cixin Lu, and Lawrence Wright (these are names I’m reading off from my reading journal, which I’ve kept since 2018, the year I really started to read for pleasure again).

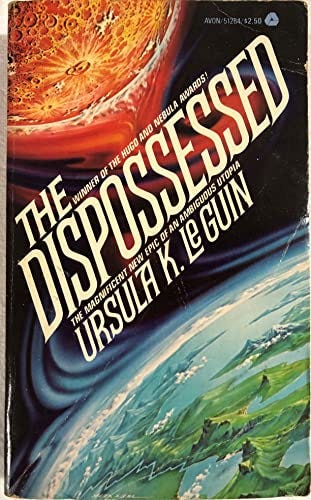

I read several Le Guin novels in a relatively short span of time: The Left Hand of Darkness, The Lathe of Heaven, various Earthsea books, The Word for World is Forest. But one book stood out to me and stuck with me: The Dispossessed. That’s the book that made me fall in love with Le Guin, and it’s the book we’ll be reading together next month as part of our 2025 philosophical read-alongs.

The Dispossessed is utopian fiction. The book centers on two worlds: Urras and her habitable moon Anarres. Urras is a world much like Earth, while Anarres has been settled by a group of idealistic anarchists. Shivek, a scientist from Anarres, travels to Urras for the purpose of scientific collaboration. He soon finds himself caught between worlds, pulled in many directions.

Le Guin clearly has sympathies with the anarchists. Non-violent anarchism was one of her philosophical loves, and she set out to write a utopia for this ideology. This book is sometimes read as a defense of anarchism; the glowing praise you’ll find online about it seems to ignore that the subtitle refers to it as an ambiguous utopia. Le Guin ultimately couldn’t bring herself to write a book like Utopia. Everything is too complicated.

This is why I love Le Guin. Her work is philosophically sophisticated, self-aware, and even self-critical. The Left Hand of Darkness isn’t about how everything would be just fine if we snapped our fingers and abolished gender; it is an exploration of the complicated layers of gendered experience (often linked to sex, as it is explicitly in The Left Hand of Darkness) from two radically different perspectives. Le Guin even revisited that idea explicitly in two separate essays — the second of which consisted of annotations to her original ‘Is Gender Necessary?’ Le Guin was a thinker who continued to grapple with ideas. She did not merely pronounce them from on high. She invited you to start grappling as well.

Of course, Le Guin is not without her faults. A friend of mine – a veteran book critic – thinks many of her works are a touch overwritten (a notable exception being The Lathe of Heaven). Other readers find that Le Guin is preachy, always interested in getting you to believe what she believes. (I disagree, for reasons I’ve outlined above.) Still others just hate her politics. I invite you to see for yourself — it would make for good discussion during our read-along.

B.D. McClay, writer of

here on Substack, recently published a piece called ‘le guin is not your unproblematic grandma.’ The focus of McClay’s piece is the tendency to valorize Le Guin in critical discussions — she is one of the good ones, we like to say.This is the crux of the issue:

The hard sugar candy shell with which people have surrounded Le Guin defines her almost entirely negatively and makes her seem, frankly, stupid. If you read her essays or her letters or—hell!—her fiction, you get somebody more complicated, more prone to self-criticism, and more interesting. But it’s like Le Guin is so virtuosic that unless you’re a bit of a crank (like Russ) people just sit there in awe. And I care about this because… I do think Le Guin is a great artist and I want to see her talked about like one, and not just with reverence.

I love Le Guin because she is a great artist, and I think that as a great artist she is worthy of criticism – real, genuine criticism – because her work deserves, and can withstand, that level of engagement.

By treating her work this way, we’re also showing Le Guin a good deal of respect. She is worthy of being treated like a human being, which means being considered a woman with flaws. Treating her as a candy-coated model of perfection isn’t treating her like a human being; it’s treating her like a literary Barbie upon which you can project your idealized fantasies.

There’s an anecdote, I think about Margaret Atwood (I cannot find the quote, sadly). Atwood was asked how she comes up with such interesting, strong, complicated female characters, especially characters that are compelling despite (or because of) their flaws. Atwood responded with something like ‘It’s easy. I remember that women are people.’ It’s helpful to keep that in mind not just when reading about women characters, but when reading fiction by women. They’re people — that brings along quite a bit of good, but it means perfection is often out of reach.

If that sounds interesting to you, then you should read The Dispossessed with me in February and March. The schedule is here:

February 10: Introduction to Le Guin’s life and work

February 17: Chapters 1-3

February 24: Chapters 4-6

March 2: Members-Only Zoom Call, 8PM Eastern

March 3: Chapters 7-9

March 10: Chapters 10-13

March 13: Members-Only Zoom Call, 3PM Eastern

The read-alongs are free. Sometimes I write some extra posts for paid subscribers, and the Zoom calls are exclusively for those who financially support me, but the main read-along posts are available to everyone. I invite you to buy a copy of The Dispossessed and get involved with our discussion.

I look forward to reading with you.

I love these thoughts. I greatly enjoyed The Dispossessed, and part of what I liked so much about it is that the "utopia" was not presented as a hollow childish ideal at all, but rather a complicated culture with genuine political, social, and existential issues.

every edition seems to have a cool cover!