For the rest of August, I’m offering a 20% discount on annual subscriptions to Walking Away. To subscribe and support my work on Substack and YouTube, just go to this link.

I’m supposed to be finishing up a post about Aristotle this morning, but last night, we had one of our monthly members-only Zoom calls, and while that left me quite satisfied, it also left me quite tired. So I’m getting a late start to this Monday and will write something a little lighter. (The read-along post for Book VII of Nicomachean Ethics will be out Wednesday.)

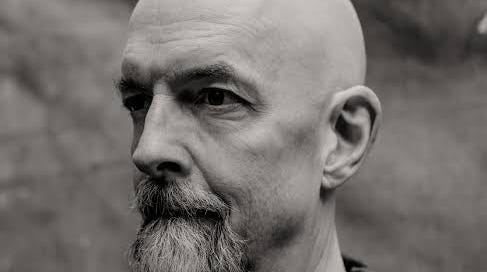

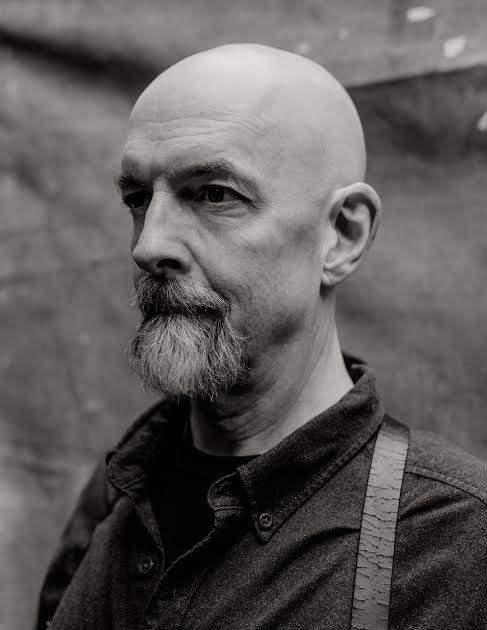

The great and powerful Neal Stephenson – author of one of Anathem, one of my favorite works of speculative fiction – is a fellow writer here on Substack. His newsletter,

, is dedicated to the intersection of technology and storytelling. It is a good publication that I think you’d enjoy.Recently, he published something a little bit different: a post about a single word.

’Deeply,’ Stephenson says, has become the new ‘very.’ An intensifier without any intensity, a modifier that fails to meaningfully modify, a bit of caulk writers use to fill in the gaps in their arguments. But ‘deeply’ is worse, he says, because it adds a moralistic overtone to the sentence.

I’ve had similar, though less refined, thoughts about ‘deeply,’ though I’m sure I’ve also used it too often (even here on Walking Away). After reading Stephenson’s post, I made a pledge to myself to excise ‘deeply’ from my prose going forward. (I’m rewriting a book proposal this month, and that is a good occasion to pay close attention to your use of language, especially your bad habits.)

But there are a few other words I’d like to stop using, too.

‘Fundamentally,’ while not as common as ‘deeply,’ brings with it several of ‘deeply’'s problems. ‘Fundamentally’ is sometimes used as a clumsy alternative to ‘very,’ and we’ll all agree (as right-thinking people) to stop using it in that way immediately. There is, however, an edge case we need to consider.

Sometimes when analyzing some problem – a philosophical puzzle, a social ill, whatever – we realize that we’ve been focusing on the wrong cause. Say that you’re writing about the loneliness epidemic, and you have come to believe that the root cause of loneliness is excessive phone use. You might say, ‘Fundamentally, the problem of loneliness is a problem of excessive phone use.’ ‘Fundamentally’ is a load-bearing word in that sentence. You would be saying that the social ill you want to solve reduces to another problem. It is similar to a mathematician saying that in order to prove theorem A, all you need to do is prove theorem B. (But consider that one could use a spatial metaphor as an alternative: ‘At bottom.’)

I don’t mind this use of ‘fundamentally,’ but edge cases don’t make for good rules. When someone says, e.g., ‘This is a fundamental truth’ or ‘This is fundamentally true,’ nine times out of ten they are using ‘fundamentally’ as a intensifier that, like ‘very’ and ‘deeply’, lacks intensity. While ‘fundamentally’ does not have the moralistic overtones of ‘deeply,’ it does add a level of pseudo-intellectual profundity to the phrase that is best avoided.

What should you say instead? The best course of action is to think about what it is you are trying to express. Sometimes ‘fundamentally’ is being used in the foundational, rock-bottom, root cause sense. Find a word that expresses that more clearly. Other times, ‘fundamentally’ is used to mean that a claim is a fixed point in your reason — in other words, an assumption one is that willing to give up (or even perhaps evaluate). There are better ways to express this, too.

There is a whole class of words I need to stop using, and as I look back on my recent writings and see how frequently these words are used, I know this will be difficult. These are the hedging words: ‘in some sense,’ ‘something like,’ ‘perhaps,’ and so on.

I write quite frequently, and that means that what you often read on Walking Away are my thoughts in progress. It is why I return to the same themes several times; I’m still working through the issues. What this means, however, is that I don’t always think through the exact line of argumentation.

When I was working on my PhD, the expectation was the exact opposite. As an analytic philosopher, I was taught to emphasize rigor and clarity. With clarity comes confidence. Here’s an example – a concluding paragraph to a paper I wrote on the semantics of the truth predicate – that I think shows this well:

Thee best argument for the truth predicate being a gradable adjective comes in two stages. During the first stage, one would argue that true behaves similarly to gradable adjectives such as tall and flat. I have argued that this is so, by pointing to the fact that true takes modifiers such as very and not at all, and that true can appear in comparative constructions. During the second stage, one would show how the semantics of the truth predicate could be given using the machinery already employed in the analysis of gradable adjectives. I have argued that this is so, using the semantics given by Kennedy & McNally. We can explain both bare and gradable truth-ascriptions in a straightforward way. So while my conclusion about the truth predicate may seem unorthodox, it is in an important sense conservative – we take on no new commitments about how we should analyze gradable terms, for instance, and we can help ourselves to the machinery of standard model-theoretic semantics. Thus, I conclude that the truth predicate is indeed a gradable adjective.

That may not be the most compelling read – it is very academic – but I do like it. I have a thesis. I am clearly stating that thesis. I am summarizing my reasons for that thesis. I am preparing the reader to move into the second half of the paper, in which I will go on to address complications and objections.

There are no hedging expressions in that paragraph. I meant what I said.

As you move to writing for a wider audience, your style has to change. I have accepted that, and I think that, in some ways, my writing has improved. I am getting better at weaving a narrative into my prose. I can identify examples that will illustrate the point to those who are not professional philosophers. I can occasionally turn a half-decent phrase.

In other ways, I have gotten worse. I am sloppier than I used to be in both thought and style. Those hedging words I mentioned above are the sort of words that allow me to get away with the sloppiness. It is a lazy way to think and write. So, I will stop using them.

This is the beginning of a larger project, I realize. I’ll need to remain vigilant, always looking out for those words that let me get away with poor thinking.

Labor is always better when accompanied by fellow works, so let me ask: what other words should we avoid?

I am too affectionate to the word "perhaps" to let it go unused, what with its lovely sound, its tentative quality, and that beautiful song from an old movie...

This said, I should probably lose some bad habits myself. Words need to be used with care and precision, and none is useless in itself, when used in a context in which it NEEDS to be used.

I was taught to be wary of words like "clearly" or "obviously", because they often signify a writer trying to convince themselves of the fact. Now anytime I see those words (in my own writing and others'), I immediately asked the question "is it clear? is it obvious?" I find often it is not.