Writing Advice from C.S. Lewis, Part 2

Get clear, avoid ambiguity (and typewriters), and keep your old work nearby.

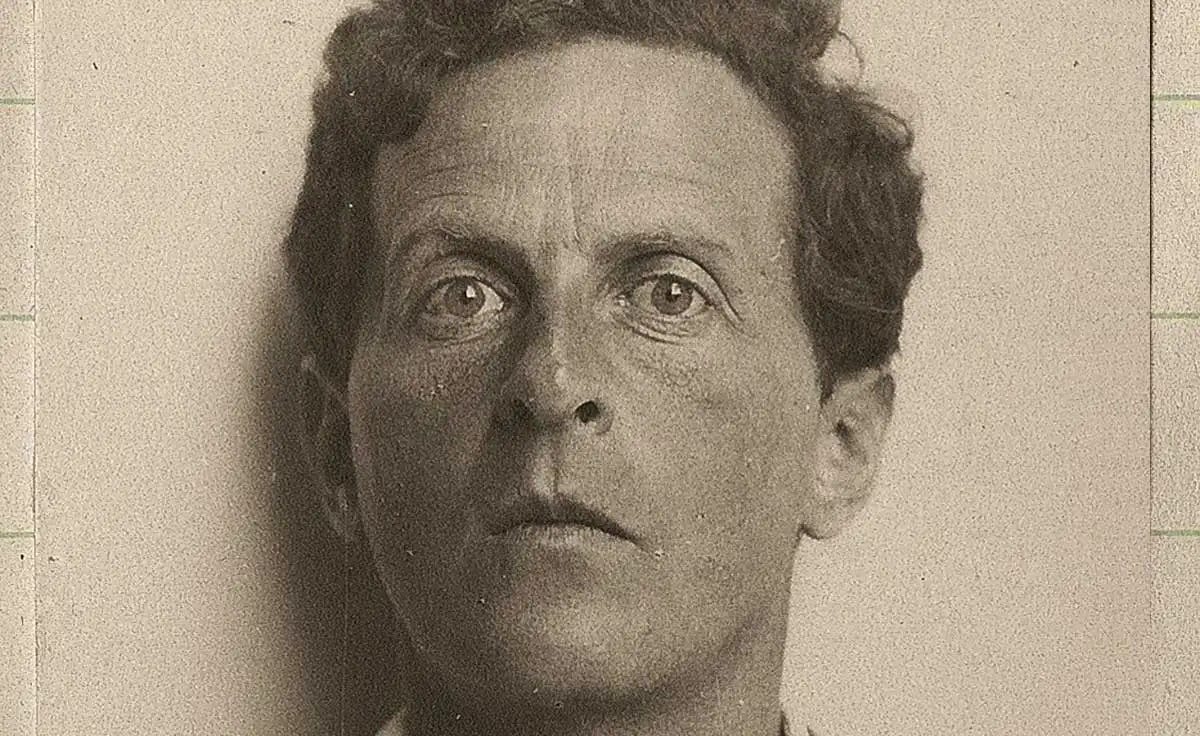

When asked for advice on how to become a better writer, C.S. Lewis sent his correspondent the following list.

Turn off the radio.

Read all the good books you can, and avoid nearly all magazines.

Always write (and read) with the ear, not the eye. You should hear every sentence you write as if it was being read aloud or spoken. If it does not sound nice, try again.

Write about what really interests you, whether it is real things or imaginary things, and nothing else. (Notice this means that if you are interested only in writing you will never be a writer, because you will have nothing to write about . . .)

Take great pains to be clear. Remember that though you start by knowing what you mean, the reader doesn’t, and a single ill-chosen word may lead him to a total misunderstanding. In a story it is terribly easy just to forget that you have not told the reader something that he needs to know—the whole picture is so clear in your own mind that you forget that it isn’t the same in his.’

When you give up a bit of work don’t (unless it is hopelessly bad) throw it away. Put it in a drawer. It may come in useful later. Much of my best work, or what I think my best, is the re-writing of things begun and abandoned years earlier.

Don’t use a typewriter. The noise will destroy your sense of rhythm, which still needs years of training.

Be sure you know the meaning (or meanings) of every word you use.

Last week, we discussed items 1-4. Today, I’ll write about the second half of the list.

You can read last week’s discussion here:

Take great pains to be clear

I was trained as an analytic philosopher. For those who would don’t know, analytic philosophy was a 20th century movement that came to dominate the Anglophone philosophical world. We still feel the effects of Russell, Moore, Wittgenstein, Frege, Quine, etc.

Analytic philosophy focuses almost pathologically on two virtues: rigor and clarity. Rigor here is usually meant formally. We try our best to make formal arguments that are valid, ideally sound. This usually means paying careful attention to the precise meaning of the words we employ. We strive for clarity through disambiguation, drawing distinctions, and hedging as needed.

A consequence of this two-fold pathology is that our prose is often unpleasant. It just is not that fun to read. As a writer, you want your prose to be enjoyable — but as Lewis warns, this does not mean you should give up on being clear.

Lewis may be overly charitable when he says that you, the writer, know what you mean. Many times we don’t know exactly what it is that we are trying to say. We discover that during the process of writing — and more often during the process of revision. It is there that we are able to look for those ill-chosen words that lead to total misunderstanding.

While pursuing clarity at the expense of everything else can make the writing unbearable to read – thus the need to also write with the ear, as we discussed last week – I would rather have the problem of being too clear as opposed to being hopelessly unclear. Because if you do not care about clarity at all, then you have abandoned your reader.

After all, the point of writing is to express an idea. And not just to express an idea for yourself or to shout it into the void, but to have that idea lodged in the mind of another. If you give up on clarity, you’ve simply given up on writing.

Don’t throw work away

This one should be obvious, but when I speak to younger writers I find out that it is not.

Young writers and creatives tend to have decent tastes. If they didn’t have decent tastes, they likely wouldn’t be inspired to write or make art of any kind. Their tastes allow them to be inspired, but it does not guarantee that they will be able to bring that inspiration into reality.

Ira Glass of This American Life spoke about this eloquently, describing what he calls the ‘taste gap.’

When you are in the worst of the taste gap, you will not be happy with what you’ve written. You’re frustrated, maybe even angry, or just a little bit embarrassed, so you want to throw your work away. You rip the page out of your notebook. You delete the file. You act like it never existed. All is well.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Commonplace Philosophy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.