The life of the mind is for everyone

Maybe the education system failed you, or maybe you failed yourself. Maybe you never thought reading good books was something you could do.

Tomorrow (October 20, 8PM Eastern) we have our monthly members-only call. I’ll send a link out to members about an hour beforehand. If you want to join that call, and especially if you want to talk about Mrs Dalloway, subscribe.

Over on my YouTube channel, I published a video on the decline of reading.

In that video, I’m building on a larger conversation on the subject. At The Atlantic, Rose Horowitch had written – quite contentiously, based on online commentary – of a phenomenon of elite college students who couldn’t, for example, read a novel in a week. On YouTube, the fantastic PBS series Otherwords had recently published a very informative video about the reading wars and the failures of whole language learning. The conversation was not limited to a single article in The Atlantic and a 9 minute explainer video, either; I’ve seen it on Twitter, heard it in person from professors and friends, and followed the surveys published by Gallup for several years.

My thesis is fairly simple, though not as simple as some have suggested. I believe that there are two major contributing factors to the decline of reading: failures in pedagogy and the rise of digital distractions. On the pedagogical front, this is also multifaceted; the problems begin with how we teach reading to young children, and they are exacerbated by how much emphasis is placed on metrics and standardized tests. The problem of digital distractions could be more easily summarized: it’s the phones. Your smartphone, despite all of its wonders, is making you dumber.

This relates quite closely to the read-along of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics we completed over the summer. Recall that in that work, Aristotle is giving a theory of the good life, and near the end of this discussion he emphasizes the importance of contemplation in that life. Reading is a crucial part of the contemplative life, since contemplation here could also be rendered as systematic truth-seeking. Contemplation is how we make sense of the world, and reading is the best technology ever invented for that project.

Contemplation – theôria in the Greek – is a peculiar function of human beings. It is something that only we can do, Aristotle says, and this he reasons indicates that contemplation is essential to a virtuous human life. A life of virtue that does not have contemplation, Aristotle would say, could only be happy in a secondary sort of way. It would lack that fullness that the contemplative life would possess. To live a life of contemplation, you need leisure. Leisure for Aristotle is time spent away from necessary labor, the sort of labor that you do to meet your obligations or fulfill your needs. For many people in Aristotle’s time, it would essentially be impossible to live a life of contemplation. Material circumstances would bar them from the best human life.

Because of this consequence, Aristotle is sometimes called an elitist. (I’ve even said it myself!) Only the elite are capable of living the best kind of life, and that would seem to be textbook elitism.

Yet, there is surely more to the story. After all, this kind of higher life is available to more and more people now, certainly more than in Aristotle’s day. Fewer people are forced to live lives of subsistence farming; while many workers in the world do live lives of toil, the overall portion has declined. Leisure in Aristotle’s sense has become more evenly distributed — though, I must say to avoid being misread, the fact that something has become more evenly distributed does not mean that it is evenly distributed full top.

It may seem unlikely, but we could live in a world where everyone has access to some leisure time. We may not reach the blissful 20 hour workweek predicted by William Morris or Bertrand Russell, but we could have a world where everyone had the ability to engage in contemplation should they so choose. The highest form of life, in Aristotle’s view, could be available to all.

On this way of thinking, Aristotle need not be viewed as an elitist — or, at least, we sympathizers with Aristotle need not share in his Athenian elitism. The life of the mind is for everyone, we can say, and a world in which this is realizable could be on the horizon.

If that is true, then the life of the mind is (or will be) available to everyone, but we have to make the most of it.

In my video, I received a great many comments speculating about other reasons why college students may not be able to read a book in a week. One of the most common speculations was that they simply did not have time. Poorer students work jobs, for instance — but this does not explain why Columbia students cannot read a novel in a week, since I expect that the vast majority of Columbia students aren’t poor. Several students, some saying they were at elite colleges, chimed in to say that they were busy with other things, extracurriculars being top of the list.

We could go on at length about this. Economically, it may make sense for students to focus on extracurriculars; it will set them apart when they apply to law school or their MBA programs. But there is something tragic about the fact that students at some of the best universities in the world cannot bring themselves to focus on the world-class education that they are being offered. I may understand why they are doing what they are doing, but it makes my chest tighten and my fist clench.

In part, this is because I nearly squandered my own college education. I was not a good student in my undergraduate days — I skipped class, focused on activism and activities (and drinking), and skimmed the reading. I somehow got into a PhD program, but that had to be luck. I had an opportunity to learn so much, and for a very long time I acted as if this were an inconvenience. Undergrad was something I just needed to get done, I reasoned, before I went on to the real work of a PhD; this is laughable in hindsight, but I never claimed that my twenty-something self was wise.

Now I’m in my thirties and I see all the gaps in my education. I see that I was served by university system that was, at least structurally, there to satisfy my desires as a customer rather than to form me as a student. I see that I failed to be appreciative of the historical anamoly that is a public liberal arts education. I see that I am still making up for lost time.

But here is the good news: I can make up for lost time. You can too, if that applies. The life of the mind is for everyone, even if you’re late to the party.

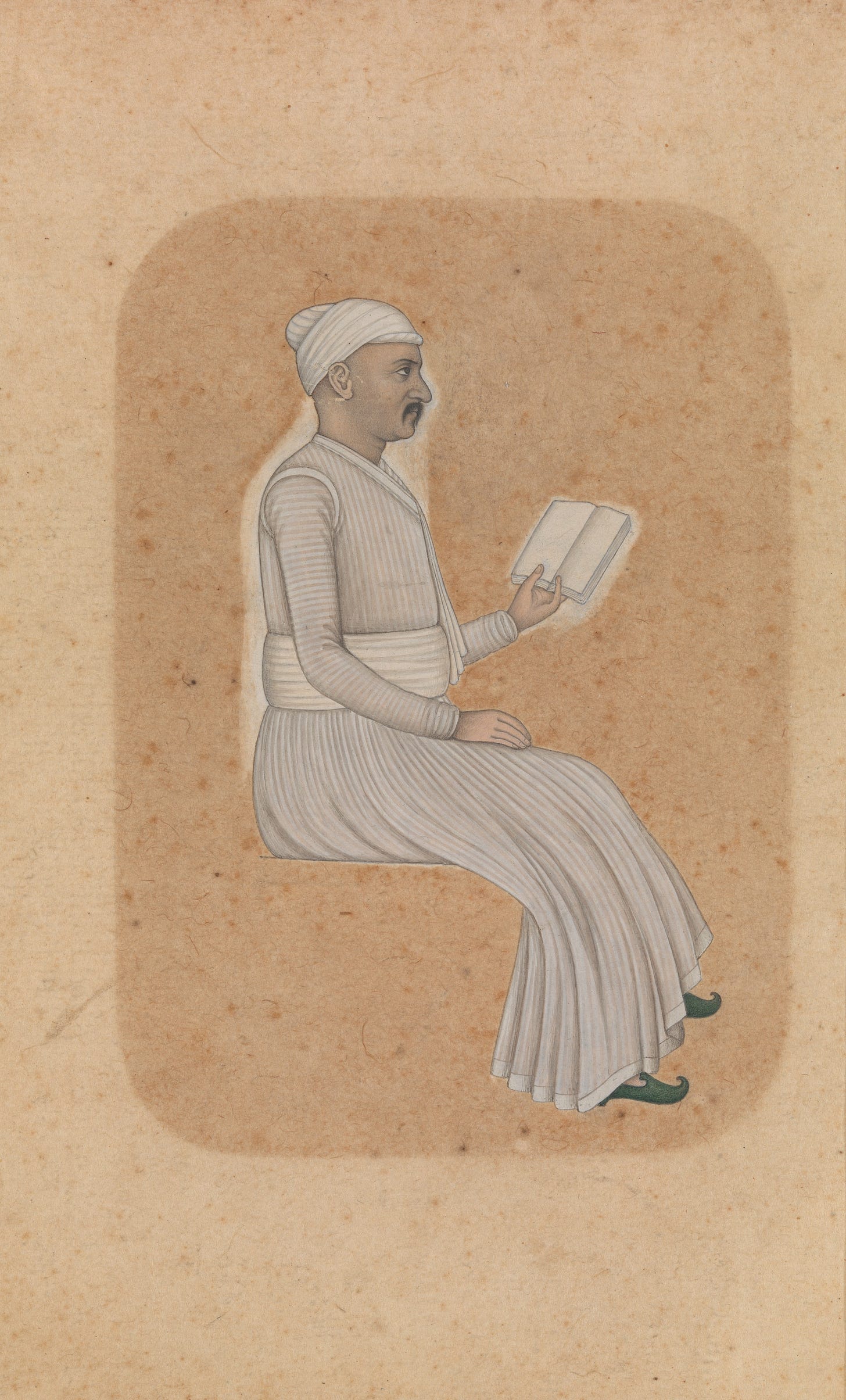

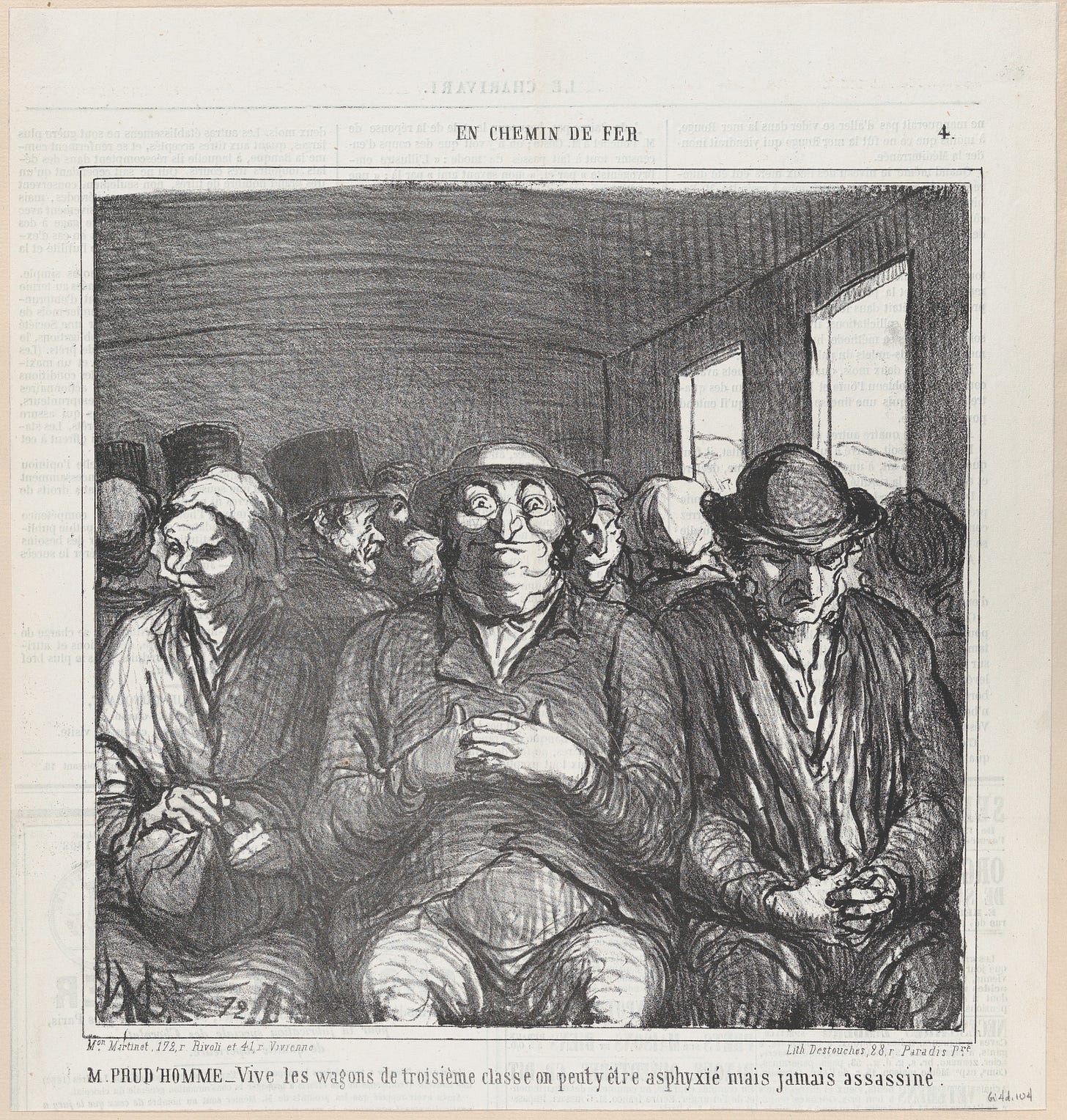

A friend of mine, L., works for the railway. She does not have a college degree. Yet, she is one of the most intellectually engaged people I know. She reads whenever she can. She can talk about poetry, literature, and the contours of Marxist theory. Her intellectual life is not dependent on a university education, and she does not seem hampered by a lack of a degree. The life of the mind is for everyone, even if you didn’t go to school.

The Catherine Project, founded by Zena Hitz of St. John’s College, runs free online reading groups, and they’ve expanded to fuller seminars. These are open to anyone over the age of 16, and groups regularly have a mix of participants with very different educational backgrounds. The life of the mind is for everyone, even if you just join a Zoom call once per week.

We read books together here at Commonplace Philosophy: first Aristotle, then Woolf, soon Arendt. (A schedule for 2024-2025 is available.) In our monthly Zoom calls, I have seen PhDs, college students, lifelong learners, and just about everything else I can think of. The life of the mind is for everyone, even if you just want to follow along on this newsletter.

Maybe the education system failed you, or maybe you failed yourself. Maybe you are a slave to the devil in your pocket and you need to rebuild your focus. Maybe you never thought reading good books was something you could do. It doesn’t matter. The life of the mind is for everyone; it is even for you.

I kind of have no choice but to have the life of the mind - because I was born disabled. I have a lot of medical issues, chronic pain, and can't work. But I can read and think. I love learning and reading. I struggled with reading comprehension in school but in my mid 20s (i'm 35 now) I figured that out on my own and now i'm an avid reader. I graduated high school in 2007 - and that's it.

I'm finally thriving and being who I want to be, and I love philosophy and to read and think. So while I do not love being disabled, and there are things I wish I could do that I can't, I *do* love the fact it gives me time to contemplate and read. I saw your video from YT recommending it and subbed.

Thanks Jared, as an academic who has taught both in “elite” and “global” colleges i have definitely seen the decline in reading among students. I feel it also reflects a general decline in reading among all adults that is, as you point out, difficult to pinpoint. Hell, I have a hard time reading and focusing myself! And I honestly sometime feel the judgemental eye of my ancestors who worked the railways, raised families, lived through wars and still left behind more annotated books and notebooks than I ever will. 🙊