Announcing the 2026 Philosophical Book Club

Philosophy of Technology, Authenticity, and the Internet

I’m very excited to be announcing this today: I have a schedule for the 2026 book club. Our theme will be the philosophy of technology, with an emphasis on the internet and authenticity. I’ve picked 12 books, along with supplementary essays, for us to read together. Hopefully, we will all work together to get a better grasp on what the internet, and technology more broadly, is doing to us.

This post has the schedule (broken down by month). You’ll find that below. (It may be too long for your inbox, so click through to Substack to read the rest of it.) Before we get to the schedule, I want to talk about the rationale and structure of the 2026 book club.

Why I Chose These Books

To make things manageable, we will typically read one book per month, along with at least one essay. (Sometimes we’ll omit the essay, other times the ‘essay’ be selections from a second book.) Sometimes these books are works of philosophy; other times I’m assigning novels; sometimes we’ll turn to adjacent fields like social theory or history to broaden the discussion.

Some readers will find these selections very challenging. Others will find them far from challenging, perhaps even boring. And still others will wonder why I excluded certain figures.

First, you must keep in mind that this is only a year-long project. I had roughly double the number of books on my shortlist, so I am aware that there are plenty of thinkers that are left out. There is a lack of older philosophers, particularly before the 20th century; plausibly ,we could have revisited Plato and Aristotle, perhaps even read Hesiod, and then worked our way forward through history. I had to make many difficult decisions. I tried to find room for Habermas, Foucault, Yuk Hui, Yevgeny Zamyatin, and more — I just could not make it all fit without overwhelming everyone. I wanted to make sure I was assigning no more than (roughly) 50 pages in a week.

Second, you must keep in mind that the readership of this audience is broad. Some have PhDs in philosophy; some have never read a full text of philosophy before. Some prefer fiction, others prefer classic nonfiction tomes. I tried to strike an appropriate balance with the readings by including philosophy, fiction, and some nonfiction books written for a popular audience.

Third, you must keep in mind that these books reflect my interests. If all goes well, I’ll one day write my own book on the philosophy of technology. When I write, I tend to draw on philosophers and fiction in equal measure, with a heavy emphasis on science fiction. So, this reading list in part reflects what I want to read, given what I want to write.

Format

Last year, we followed a simple structure for our read-alongs. I posted a schedule, published a weekly post on that week’s readings, and then we had sporadic Zoom calls.

In 2026, we’re going to tinker with that format a bit. I’ll still post on Monday’s about that week’s reading. But the Zoom calls will now be monthly, serving as a wrap-up call for the month’s readings. These calls are our opportunity to discuss the month’s readings together. This may change, but I think in 2026 we’ll have our Zoom calls on the last Sunday of every month, but to make it possible for others to join, we’ll have it at 4 PM Eastern as opposed to 8 PM. Maybe some Europeans will find it easier to join? You can give me feedback down below.

To facilitate additional discussion (and to avoid cluttering your inbox), I’ll try to use Substack Chat more. You can also start your own threads there.

Clarification below, added September 1.

This book club is available to anyone to subscribes – free or paid – to Commonplace Philosophy. If you look back at my old posts, you’ll see quite a few sent out about a particular text. (As I write, the book we’re reading is Zhuangzi.) We follow a reading schedule, which I make public for everyone, and discuss the readings in the comments. That’s the whole format.

You can, of course, pay me. I always appreciate that. But that payment is not necessary to participate in the main discussion posts; the main benefits are that you can join the Zoom calls and know that you have helped support my work.

End clarification.

Below, I’ll provide a longer rationale for each book, but here is the condensed schedule:

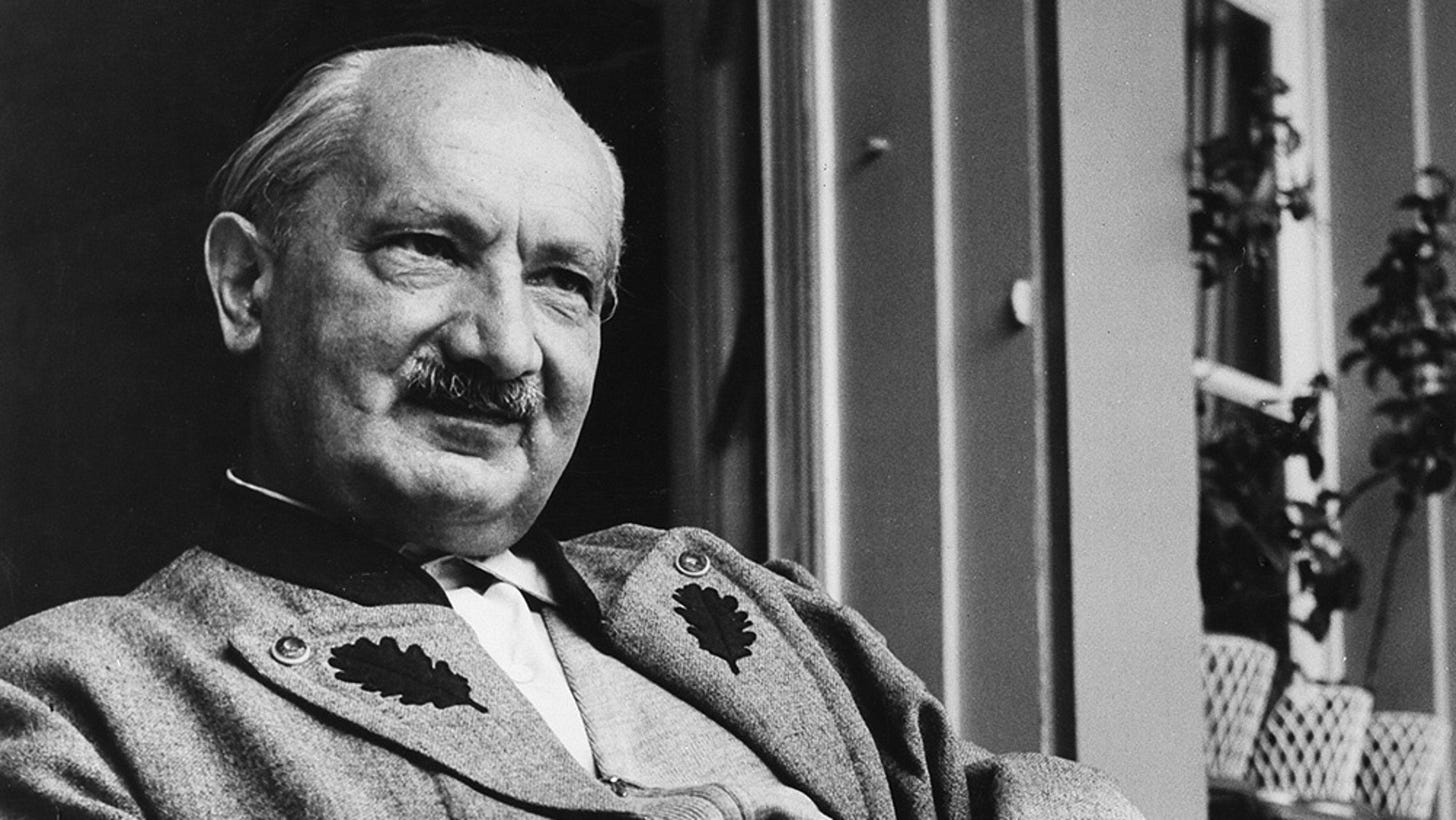

January: Non-Things: Upheaval in the Life World by Byung-Chul Han and ‘The Question Concerning Technology’ by Martin Heidegger (Link to PDF)

February: The Circle by Dave Eggers and ‘The Narcissistic Personality of Our Time’ by Christopher Lasch

March: You and Your Profile by Hans-Georg Moeller and Paul J. D’Ambrosio and ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’ by Donna Haraway (Link to PDF)

April: The Right to Oblivion by Lowry Pressly and ‘The Girl Who Was Plugged In’ by James Tiptree Jr.

May: Alone Together by Sherry Turkle

June: The Ethics of Authenticity by Charles Taylor and ‘Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer’ (Link to PDF) and ‘Feminism, the Body, and the Machine’ (Link to PDF) by Wendell Berry.

July: Pattern Recognition by William Gibson and “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” by Walter Benjamin (Link to PDF).

August: Technics & Civilization by Lewis Mumford

September: What is Called Thinking? by Martin Heidegger

October: Technopoly by Neil Postman and Filterworld by Kyle Chayka

November: Stop All the Clocks by Noah Kumin, ‘The Medium is the Medium’ by Nicholas Carr, and Atlas of AI by Karen Crawford

December: The Life of the Mind by Hannah Arendt (part 1).

January

To start, we’ll read one book and one essay. The first book is slim, but given that it is by Byung-Chul Han it won’t be the breeziest read. The essay is by Heidegger, so of course, it is going to be difficult.

Non-Things: Upheaval in the Life World by Byung-Chul Han

‘The Question Concerning Technology’ by Martin Heidegger (Link to PDF)

These are foundational readings for this discussion. Both Han and Heidegger are grappling with what it means to be a human being in the face of technology. Han’s writing is famously suggestive, sometimes making it hard to follow the argument; Heidegger’s writing is famously cryptic, making it even more difficult. But we’ll take a month to read these in the hope of constructing a foundation on which we can base further readings.

February

In February, we’ll read a novel and a book chapter. The novel is The Circle by Dave Eggers, a fairly recent work warning us against the powers of social media on our shared social world. The chapter is Chapter 2 of Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism, ‘The Narcissistic Personality of Our Time.’ (You can find that book on the Internet Archive, but it is also worth owning a copy.)

Here is a description of The Circle:

When Mae Holland is hired to work for the Circle, the world’s most powerful internet company, she feels she’s been given the opportunity of a lifetime. The Circle, run out of a sprawling California campus, links users’ personal emails, social media, banking, and purchasing with their universal operating system, resulting in one online identity and a new age of civility and transparency.

As Mae tours the open-plan office spaces, the towering glass dining facilities, the cozy dorms for those who spend nights at work, she is thrilled with the company’s modernity and activity. There are parties that last through the night, there are famous musicians playing on the lawn, there are athletic activities and clubs and brunches, and even an aquarium of rare fish retrieved from the Marianas Trench by the CEO.

Mae can’t believe her luck, her great fortune to work for the most influential company in the world—even as life beyond the campus grows distant, even as a strange encounter with a colleague leaves her shaken, even as her role at the Circle becomes increasingly public.

What begins as the captivating story of one woman’s ambition and idealism soon becomes a heart-racing novel of suspense, raising questions about memory, history, privacy, democracy, and the limits of human knowledge.

March

In March, we’ll turn to You and Your Profile by Hans-Georg Moeller and Paul J. D’Ambrosio.

Here is how the publisher describes You and Your Profile:

More and more, we present ourselves and encounter others through profiles. A profile shows us not as we are seen directly but how we are perceived by a broader public. As we observe how others observe us, we calibrate our self-presentation accordingly. Profile-based identity is evident everywhere from pop culture to politics, marketing to morality. But all too often critics simply denounce this alleged superficiality in defense of some supposedly pure ideal of authentic or sincere expression.

This book argues that the profile marks an epochal shift in our concept of identity and demonstrates why that matters. You and Your Profile blends social theory, philosophy, and cultural critique to unfold an exploration of the way we have come to experience the world. Instead of polemicizing against the profile, Hans-Georg Moeller and Paul J. D’Ambrosio outline how it works, how we readily apply it in our daily lives, and how it shapes our values―personally, economically, and ethically. They develop a practical vocabulary of life in the digital age. Informed by the Daoist tradition, they suggest strategies for handling the pressure of social media by distancing oneself from one’s public face. A deft and wide-ranging consideration of our era’s identity crisis, this book provides vital clues on how to stay sane in a time of proliferating profiles.

To supplement this book, we’ll also read selections from Haraway’s ‘A Cyborg Manifesto.’

April

We also need to discuss the issue of privacy in light of omnipresent surveillance technology, so in April, we’ll read Lowry Pressly’s The Right to Oblivion.

The parts of our lives that are not being surveilled and turned into data diminish each day. We are able to configure privacy settings on our devices and social media platforms, but we know our efforts pale in comparison to the scale of surveillance capitalism and algorithmic manipulation. In our hyperconnected era, many have begun to wonder whether it is still possible to live a private life, or whether it is no longer worth fighting for.

We want to make sure that we keep reading fiction, because I’ve found that fictional works tend to stimulate the best discussions on Substack. So, next we’ll read “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” by James Tiptree Jr. (note that this is the pen name of Alice Sheldon). This is a novella, about 60 pages long, and it is available in the collection Warm Worlds and Otherwise. Like The Circle, “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” is concerned with the degradation of life through technology, but the focus here is on things like advertising. We’ll treat this like our essay for the month.

May

It is impossible to discuss technology in the modern age without talking about loneliness, and so we will turn to the work of Sherry Turkle, an MIT professor who has written extensively about the ways in which technology alienates us.

Technology has become the architect of our intimacies. Online, we fall prey to the illusion of companionship, gathering thousands of Twitter and Facebook friends, and confusing tweets and wall posts with authentic communication. But this relentless connection leads to a deep solitude. MIT professor Sherry Turkle argues that as technology ramps up, our emotional lives ramp down. Based on hundreds of interviews and with a new introduction taking us to the present day, Alone Together describes changing, unsettling relationships between friends, lovers, and families.

We’ll also read some related philosophical essays on loneliness; I’ll determine which ones, exactly, as we get closer to May 2026.

June

Since Moeller and D’Ambrosio are writing about a post-authenticity world (and what could be less authentic than advertising?), this is a good opportunity for us to step back and ask questions about art and authenticity. So, we’ll read: The Ethics of Authenticity by Charles Taylor in April. We’ll also read two famous essays by Wendell Berry, ‘Why I Am not Going to Buy a Computer’(Link to PDF) and ‘Feminism, the Body, and the Machine’ (Link to PDF).

July

Returning to fiction, in June we will read Pattern Recognition by William Gibson. This is a novel about art and authenticity (in part), so we’ll also read “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” by Walter Benjamin (Link to PDF)

Cayce Pollard is a new kind of prophet—a world-renowned “coolhunter” who predicts the hottest trends. While in London to evaluate the redesign of a famous corporate logo, she’s offered a different assignment: find the creator of the obscure, enigmatic video clips being uploaded to the internet—footage that is generating massive underground buzz worldwide.

Still haunted by the memory of her missing father—a Cold War security guru who disappeared in downtown Manhattan on the morning of September 11, 2001—Cayce is soon traveling through parallel universes of marketing, globalization, and terror, heading always for the still point where the three converge. From London to Tokyo to Moscow, she follows the implications of a secret as disturbing—and compelling—as the twenty-first century promises to be...

August

Technics & Civilization by Lewis Mumford is a classic work in the philosophy and history of technology. We’re going to read all of it, or at least substantial selections, in August. This is probably the most grueling month of our book club in 2026, but it will be worth it.

Since we’re reading so many pages of Mumford, I won’t assign any additional essays.

September

By this point, we have made significant progress in the world of technology. I think we need to occasionally step back and ask questions about what it means to think in the modern world. So, September we will read What is Called Thinking? by Martin Heidegger. I would like to pair this with an essay by Hubert Dreyfus, ‘Heidegger on the Connection Between Nihilism, Art, Technology, and Politics,’ which is available in a volume from Cambridge. I have yet to find a PDF, however, and I do not want to ask you to buy an expensive book for a single essay, so this pairing may change.

October

In October, we’ll read a significantly easier text, though it is still very important): Technopoly by Neil Postman. We’ll supplement this with selections from Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture by Kyle Chayka. Both of these books are about, very broadly, the way technology has come to dominate and shape culture.

November

Stop All the Clocks by Noah Kumin is a new novel, out just in 2025, so it will be a refreshing read.

Mona Veigh was feeling burnt out from the tech world—and life in general. Following the death of her unconventional colleague, Avram Parr, and the collapse of her AI company that left her a hefty cash-out, Mona retreated to her home on Roosevelt Island, free to toss her phone into the East River and curl up with a good book, forever. However, strange occurrences intrude on Mona's permanent vacation and thrust her back into the world. Colleagues from her former company begin to track her down and let on that there may be more to Avram Parr’s death than meets the eye. They all seem to believe that Mona possesses the crucial information about Avram that they seek, or, if not Mona, then her creation, Hildegard—an oracle-like bot that produces eerily prophetic poetry. Stop All the Clocks is a rare literary thriller where the crux of the whodunnit isn't a person but modern life itself, where the conspiracy lies within the dark magic of digital technology—the ones and zeroes to which everyone is beholden—and the motive is the beguiling power of the words on the page.

We’ll pair this with an essay from Nicholas Carr:

I also want to read this in conjunction with selections from Karen Crawford’s Atlas of AI, though this selection may change if I can find a better and more recent book on artificial intelligence.

December

Our final book will be The Life of the Mind by Hannah Arendt. This is a very dense work as well, so we will only read part one, which is dedicated to the subject of thinking. This is an excellent companion to Heidegger’s work on thinking, and it should serve as a reminder about what it is we are doing as we investigate technology.

And now, an appeal

I give away the vast majority of my content. On a platform like YouTube, I’m compensated with a portion of the ad revenue I generate. This is a blessing and a curse. It is a blessing because it allows me to be paid for my work; if people watch, I make money, and that lets me continue to live and to produce more. It is a curse because it means I am beholden to trends, algorithmic whims, and the fickleness of advertisers.

Substack offers an alternative. I still give away most of my content for free; I think about 75% of what I write is available to everyone. I don’t want to paywall too much of what I write because I want people to be able to engage with these ideas. But it relies on some portion of my readership thinking that it is worth supporting. It relies on some people paying for a subscription.

So, I’ll ask you this. If you think a year-long guided tour of the philosophy of technology is worth having out in the world, would you consider becoming a paid subscriber to Commonplace Philosophy? You’ll be helping me make this content available to everyone.

Thanks for considering, and thanks for reading.

.

Got the email notification for this while reading and set it aside. Five seconds later thought, "you know what? That's my 2026 base reading plan right there," and jumped in. Very excited for this! Thank you for organizing this!

Couldn't have picked a topic I'd be more interested in a book club for. Hyped!