Aristotle in the Anthropocene

In a ruptured world, we need to learn to be human again.

In case you care about this sort of thing, here is a warning: this article contains spoilers for Her, Klara and the Sun, and Never Let Me Go. The Her spoilers are right at the front. You’ve been warned.

Did you ever see the movie Her? It tells the story of Theodore. His days are spent working, as most of our days are, but Theodore’s job is rather odd: he writes letters for other people. When they can’t find the words to say what needs to be said, Theodore steps in.

Unfortunately, Theodore cannot speak for himself. His marriage falls apart, and as the film progresses, Theodore begins to fall in love with his virtual assistant, Samantha.

It isn’t until the end of the film, after which Samantha has left Theodore as well (saying that the AI are going somewhere, leaving humanity behind), that Theodore is finally able to speak from the heart to another human being. He composes a letter to Catherine, sending it off to be delivered wherever she is. The scene means more if you have seen the film, of course, so if you haven’t watched it, I highly recommend making that a priority.

Her got a lot of attention for its provocative premise. Immediately people wanted to discuss the possibilities, the promises, and the pitfalls of human-AI relationships. Some saw something beautiful in them. Others (myself included) were horrified. But fundamentally, Her is about loss — not just Theodore’s loss of Catherine, but about our shared loss of a social reality, the fraying of the threads that bind us together. Her is a story about lonely people, watched by an audience of lonely people who, by and large, missed the point.

Speaking of missing the point, you may have seen this video from a new startup: Friend.

I saw this video, and dystopia began to come into focus. Friend seems to recognize that we live in a lonely world, and the founders want to fix that. Their solution is a wearable pendant powered by AI that talks to you via your phone.

The Anthropocene is a term that has yet to enter common parlance, but we are seeing it more and more. It is the technical term for a geological epoch whose defining characteristic is man-made. We are in the Anthropocene; we made the Anthropocene.

Human beings have a profound ability and desire to shape our environment. We have connected the globe via sea and air. Our continents are crossable by everyday citizens due to highways and train routes. When we run out of desirable land, we build more. Our building and infrastructure, as well as the waste we leave behind, will tell the story of our civilization long after we are gone.

The story of the Anthropocene, however, will not be centered only on what we created — what we have eliminated will also need to be included. I visited the Museum of Natural History & Science in Cincinnati many times as a child, and I can vividly recall the feeling of loss I experienced when I saw the many animals human beings had hunted to extinction: the passenger pigeon, the Eurasian auroch, the baijji, the Falkland Islands wolf, and so on. The story of humanity is not just a story of innovation but also destruction.

Innovation and destruction — both thoughts need to be kept in our mind at the same time. It is easy to think about humanity and be filled with glowering pessimism, and this is a mistake, just as it would be a mistake to only be optimistic. We create many things, and along the way we have saved many lives. The rate of global poverty refuses to go to zero, yet we have made tremendous strides in reducing poverty. Access to medicine and information exists on an unprecedented scale, but there is still vast inequality which makes the practicalities of this access difficult for many. When telling the story of humanity, which is the story of the Anthropocene, we have to tell it all, the good and the bad.

This applies equally to the story of the social realm. We live in an age of mass communication, making it easier than ever to come together and talk. I am friends with people around the world — even today, I have spoken to people in London, in China, in Utah, and I haven’t had to leave my house to do so. Yet we also live in an age of profound, crushing, persistent loneliness.

This is the problem Friend aims to solve. Are you lonely? For just a small fee, you can have a permanent, artificial friend. Maybe that’s all you need.

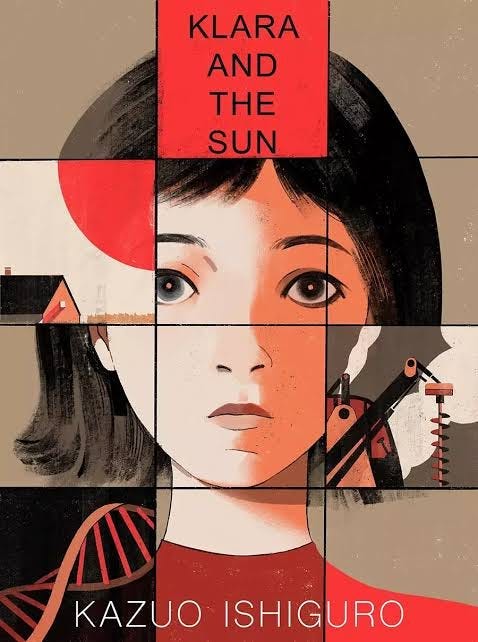

The comparisons to Her are easy, but I think another piece of art speaks more directly to the problems with Friend, and that is Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun.

Klara and the Sun is the story of Klara, an AF (the preferred shorthand for an Artificial Friend). Klara’s whole role is to be a companion to Josie, a child suffering from a mysterious illness.

(I’ll remind everyone here that I will be talking about the plot, and thus there are spoilers. But the novel is enjoyable even when you know the plot, as is true for all great works.)

Josie is ill because she has been lifted, a strange term the novel employs to refer to a kind of genetic modification. Lifted children have more potential than the non-lifted, and so even though the lifting process carries with it extreme risk of illness (we learn eventually this killed Josie’s older sister), parents who can afford to do so often will have their children go through the process.

Children in this world are tutored via online classes, getting limited opportunities to form friendships. It is never really explained why, but there is something sinister in the air — social inequality, political degradation, mistrust of anyone outside of your own home. The AFs like Klara are essentially palliative care for the chronically lonely children.

Klara and the Sun has many themes worth exploring – like Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, the novel is deeply concerned with the creation of expendable lives – but what is most relevant here is the simple fact that Klara and the Sun is a story of loneliness and a culture which refuses to fix the problem. Instead, bandages are placed over the gaping wound. This is why I think Klara and the Sun is the better parallel to Friend. We are solving loneliness not by forming authentic connections, but rather by simulating them.1

This is the social effects of the Anthropocene, I believe. This is the world we’ve made. We can innovate over and over again, always technologically progressing. But we are destroying something. And I worry that we are destroying what makes us human.

When I think of a philosopher of humanity, I think of Aristotle, and I think especially of his Nicomachean Ethics. You may have seen that here on Substack, I have been hosting a read-along of the book. The themes that arise again and again in our discussion of Nicomachean Ethics are fundamental human questions. What does it mean to be an excellent human being? What is the highest form of life? What is friendship, and why does it matter? How can I be better?

Aristotle’s conception of a human being never neglects the social. While certainly he says quite a bit about individuals, many of the virtues he discusses are fundamentally social — for instance, the entirety of Book V of Nicomachean Ethics is a discussion of justice, the virtue most concerned with the good of others. Baked into Aristotle’s conception of a good human life are social relations. His methodology presumes a social form of life, as he is always referencing the city, the laws and the lawgivers, the noble among us.

I contend that Aristotle is worth reading in the modern age because he reminds us how to be human. In the Anthropocene, we are quick to forget just what this looks like.

Looking at the promotional video for Friend, I don’t see what it gives us. I see what it takes away. A woman goes for a solo hike in the woods — and then she’s interrupted by an LLM sending her a text message. Contemplation? Gone. A man sits with his companions (friends?) playing video games and feels lonely — until, that is, his Friend sends him a message. Real social connections? Vitiated. A woman eats falafel and, instead of having an internal monologue, must voice all of her thoughts out loud. The Friend doesn’t even look like it is helping the final woman go on a date; she seems downright bothered by the presence of another human being.

Being a human being takes work. Friends – real friends, not AI wearables – demand much of us. But by doing the work, we are better off.

I am starting to think that the primary characteristic of modern life is insulation, not isolation. We want to be in a position where we are never at risk. We want to be safe. We want to be insulated from the world.

When I lost my job, for a brief period I felt unsafe. I was totally exposed. I had lost the insulation of a well-paid corporate job. Suddenly, the world could affect me. My actions had consequences. I had to face the (rather terrifying) thought that my decisions mattered. I eventually had to reframe this as an opportunity, an opportunity to stop being tossed about and to start voyaging, but that took some work (and some help). The loss of insulation was a real loss.

But insulation is a shield, not a filter. It doesn’t keep the bad things out; it keeps everything out. By insulating ourselves from the negatives of the world, we necessarily leave out the positives. We necessarily hinder our ability to change the world around us, to act as free and willful agents. (To paraphrase one writer: we lose the ability to be spirited men and women.) We necessarily leave out each other.

Going to a party is a great thing to do, but it carries with it risk. You will be able to meet people, have great conversations, and so on. You might enjoy yourself. But maybe you’ll drink a bit too much and make an off-color joke. Maybe you’ll forget your cologne and cause those around you to think of you as a the guy with body odor. Maybe you’ll see someone you really despise, and of course they’ll spend the evening try to talk to you. Seeing those risks, some of us choose insulation. We stop going to parties.

Some take it further: they stop going to school, trying to find work, or trying to make friends. In Japan, nearly 500,000 youths have become social recluses, called hikkomori. These individuals spend nearly all day in their homes, refusing social contact. They spend months like this, maybe even years. That’s extreme isolation and extreme insulation.

The insulated life is a safe life, and it can be a pleasant enough life. But it is a lonely life. It is a life free from vulnerability, but a life free from vulnerability is a life free from connections. The insulated life is not a full human life.

And so a final word of Friend. Don’t buy it. If you’re lonely, take a risk and go and meet someone. Pick up a hobby. Start painting watercolors in the park. Play Magic: The Gathering — those game stores don’t turn anyone away. Get off a screen for a time and find something to do. Introduce yourself to your neighbors. Join a run club. Go to the gym and strike up a conversation. Talk to a visitor at church, or tell someone you like their hat at the coffee shop, or ask someone for a recommendation at the bookstore. Do something – anything – that can build an authentic connection with a real person.

That’s what being human demands of us.

There is a complication here, which I’ll admit: Klara is clearly sentient. She is naive, but she thinks and feels like a human. A relationship with Klara, like a relationship with Samantha in Her, is a real relationship. Friend, however, is an LLM. It is not sentient. It is an imitation.

I appreciate you were only using it as one example among many potential examples of a general and alarming phenomenon, but I wrote about the Falklands fox 14 years ago (!) on my Friends of Charles Darwin website, reporting Darwin's thoughts on the (at that time) still extant creature.

http://friendsofdarwin.com/20100618-2/

Hello, thank you for your work. The part on what you call "insulation" reminded me a lot about a chapter from "what happended in the 20th century" by Sloterdjik in which he mentions spheres (both material and symbolic) which englobe us so as to fulfill all our desires. Also there is this french science fiction novelist in France named Alain Damasio which is quite popular there, that writes novels on similar issues and who's ideas are inspired I believe from philosophers like Deleuze, Spinoza and Nietzsche. He has this concept of "techno cocoon" like a nest in which we are nurtured and isolated.

Finally, I think of an italian philosopher, Emmanuel Coccia who wrote à book on the philosophy of the house, and it resonates to me with the fact that today young People but also most People (I believe) are more and more in their houses which are providing most of their desires.

Finally, there is this american thinker named Zak stein, (very interesting thinker, developemental psychologist, educator, and philosopher) talks about the dangers of humanizing LLMs (making you believe that they are humans), but also of the potentials of LLMs if they remain dehumanized, in which case they could potentially open immense new opportunities for learning especially. He wrote a book on the future of education in our (For american/west) socio-technical context, drawing on integral theory which is an interesting world of ideas. Thinking as à developemental psychologist allows to understand to some extent how rapidly can a culture change, in times as "fast" as 2024.

I am very curious myself how the integration of online community with "local" community will play out in the future with the "digitalization" of dating, hiring, politics, Wisdom, art, social communication, etc...