Final Thoughts on The Human Condition

Today marks the final post in our read-along of The Human Condition.

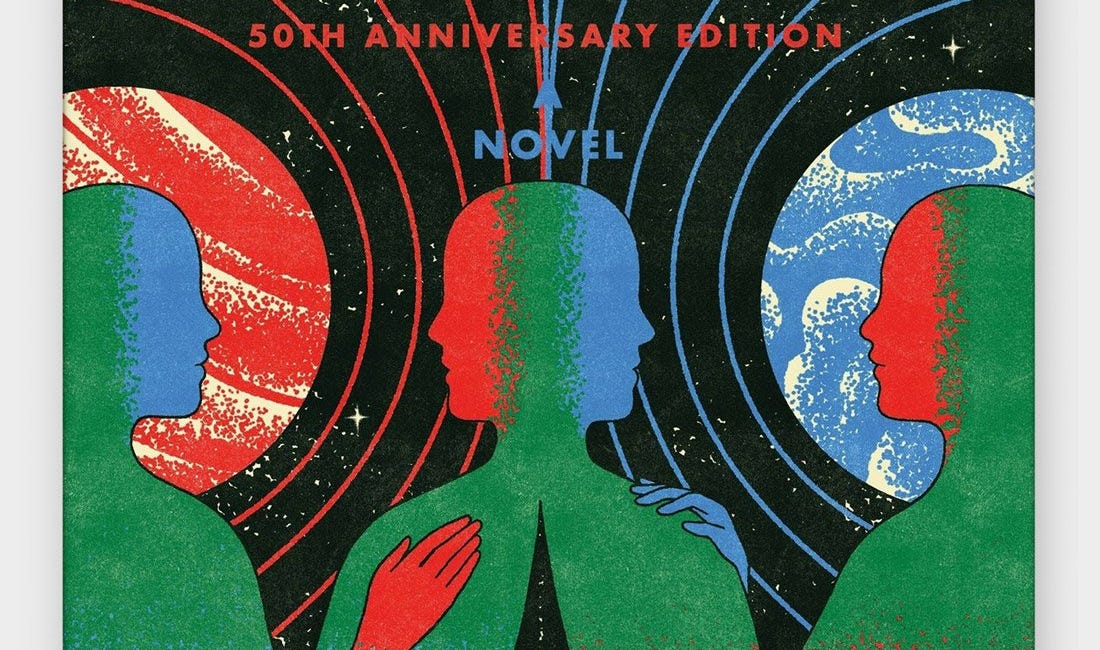

In February we’ll read Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. Here is the schedule:

February 10: Introduction to Le Guin’s life and work

February 17: Chapters 1-3

February 24: Chapters 4-6

March 2: Members-Only Zoom Call, 8PM Eastern

March 3: Chapters 7-9

March 10: Chapters 10-13

March 13: Members-Only Zoom Call, 3PM Eastern

The read-alongs are free. Sometimes I write some extra posts for paid subscribers, and the Zoom calls are exclusively for those who financially support me, but the main read-along posts are available to everyone. I invite you to buy a copy of The Dispossessed and get involved with our discussion.

Today marks the final post in our read-along of The Human Condition. I thought I had shared all of my thoughts, and my plan was to share the observations from some commenters, but as I reflected over the last week I realized I had more to say.

The Human Condition is often recommended to readers interested in either the philosophy of work or the philosophy of technology; certainly, Arendt has much to say on those matters. We’ve discussed at length the work/labor distinction, and in the background there has always been that lingering question of what our technological world is doing to us. Yet, more than anything – as the chapter on action shows – Arendt’s book is concerned with what it means to do things in the world (ideally, doing things together); doing things together is how we reveal, and perhaps form, who we are.

I had thought that I would eventually revisit the chapters on work and labor, but now I’m not so sure. I’ll likely want to revisit the chapters on action and the vita activa instead. (I am not sure I’ll want, or ever need, to revisit the entire book.) Those chapters speak directly to what it is I’m looking to do, philosophically.

What is that? Well, I am interested in the question of what it means to be a good human being, or even what it means to be a human being at all. Starting with Aristotle, we get a framework for this investigation. We identify virtues and articulate what they are, how they are distinguished from vices, and how one could cultivate them. That’s a simple way to begin.

Arendt is interested in a question, though perhaps we should say she’s interested in what it means to be human. The meaning of our lives always shifts and changes based on our environment; that’s the conditioning in the human condition. Technology, work, property, privacy — all of this affects what it means to be a human being.

I put together a list of readings for 2025, as many of you know. We’ll be reading The Dispossessed, The Republic, Aristotle’s Politics, and a few other works. All of them, I’ve come to realize, touch on this question. Arendt is just one more step along the path.

Our 2024-2025 philosophical read-alongs

I have figured out the next few read-alongs we’ll be doing here at Commonplace Philosophy, and I’ll be sharing some details with you today.

Last week, I asked commenters to share their assessments of the book. Here are a few I think were especially helpful.

First, from Raymond:

I did not see it coming at all, the conclusion of The Human Condition. Though the book argues again and again for the importance of action and the public sphere, it nevertheless ends with the following quote from Cato: “Never is he more active than when he does nothing, never is he less alone than when he is by himself.” Why?

Arendt’s central line of reasoning in The Human Condition is clear (even though many details are not): What constitutes the essence of humanity, what makes us different from all other living organisms, is our capacity to act as unique individuals and among other unique individuals. Modern society, however, has brought about the domination of our active life by animal laborans and the decline of the public sphere. As a result, Man “is on the point of developing into that animal species from which, since Darwin, he imagines he has come.” The “future of man” is at stake. So what does Arendt suggest we do? Not much, or a lot; depending on your point of view.

Arendt writes: “In this existentially most important aspect, action, too, has become an experience for the privileged few”. She continues: “Thought, finally . . . is still possible, and no doubt actual, wherever men live under the conditions of political freedom.” In these “dark times,” the only act of resistance is for every one of us to struggle to continue to think. But what does to think mean? To answer this question, Arendt decided to investigate “the life of the mind” as her next philosophical project.

Raymond’s comment can be found in full, along with the other comments I’m featuring, at last week’s post.

I’ve recently procured The Life of the Mind, and I think this is where the project naturally leads. Given comments from others over the entire read-along, I suspect many of you would be interested in that subject. How do we lead a life of the mind in the modern age? It isn’t easy — but it is possible.

Gloria asks:

I’d be curious to know which chapters or sections of The Human Condition you would consider worth reading for understanding Arendt’s core message. Say you were Arendt’s editor and could choose the parts of the book made it into the proposed essay, which sections would you choose?

The easy answer to that is the introductory chapters, some smattering from the chapters on work and labor, and the full chapters on action and the vita activa. So, you’d still read most of the book. But as others pointed out, Arendt seems to shine most brightly in essays. The Portable Hannah Arendt has several essays on this theme that shows how she would trim down the work. (I recommend ‘Labor, Work, Action.’)

And from Daniel:

I really enjoyed this book – I found a lot of different new tools for examining reality (the archimedes point turning inward, the stories of scientists who seriously discussed the philosophy of science, the shift to treating invention as a process rather than as created artifacts, the underemphasis in the modern world on the vida politica) and feel it's complemented my own perspective.

I particularly liked the (contentious) perspective that Marx actually follows from the tradition of Locke and Smith, rather than breaking from them completely. It's something I'll have to think more about. It also tied in nicely to some of my reading of Byung-Chul Han, who is definitely influenced by this book.

Han is a good comparison, as he shares many of Arendt’s sensibilities. (He also is critiqued by more strict Marxists, as Arendt often is. I think it comes down to his Romantic dispositions.)

Other comments in the thread are worth reading — there are thoughts on labor, our overwhelming world of consumption, and more.

And now we turn to The Dispossessed. Happy reading.

Jared brought up a very important point: all the readings on the read-along list for the year, if we read them thoughtfully, can serve as steps along the path to answering "What does it mean to be human?" and "What does it mean to be a good human being?"

A few months ago, I decided to treat the read-along plan as the basis of a course of study for the year, despite my reluctance to read some of the books on the list. I made this decision because I believe that the whole will be greater than the sum of its parts, so to speak; that our discussions will carry over from book to book; and our "wisdom" will accumulate and grow.

In fact, The Human Condition has already made me rethink my views about the character Mrs. Dalloway in our previous read-along. Also, now that I have started reading The Dispossessed, I can already see how Arendt's ideas can be used to analyze the story.

Hi Jared,

I fell behind with the readings owing to work, but from now on I'm following your reading schedule to the letter. I am playing catch up and I am reading The Human Condition. I am in Chapter 3. Better late than never...