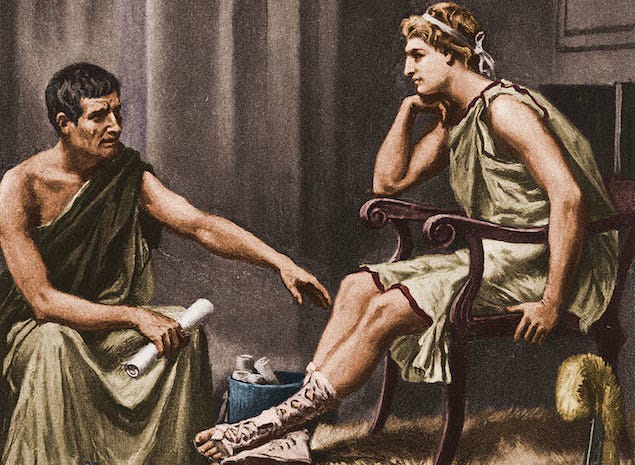

Aristotle (and Oakeshott) on Friendship

Nicomachean Ethics, 'On being conservative,' the Peripatetics vs. the Stoics

One of the most striking features of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics is that nearly one third of its content is on a single aspect of the ethical life. It is not one of the virtues — not courage, not prudence, not greatness of soul. It is not the life of contemplation, nor the life of politics. It is friendship.

Friendship is a subject which we have largely dismissed as a subject of serious study. What could be more plain and simple? Could anything be said about the matter that was not banal? But it is also a matter of extreme importance in our time. In 2019, before the pandemic and the life-altering lockdowns, 22 percent of my generation said they have no friends. Members of every generation report increased loneliness.

Over at The Atlantic, Derek Thompson gives a further assessment:

From 2003 to 2022, American men reduced their average hours of face-to-face socializing by about 30 percent. For unmarried Americans, the decline was even bigger—more than 35 percent. For teenagers, it was more than 45 percent. Boys and girls ages 15 to 19 reduced their weekly social hangouts by more than three hours a week. In short, there is no statistical record of any other period in U.S. history when people have spent more time on their own.

Given the importance a great mind such as Aristotle places on friendship, and given the decrease in friendship and sociality we are all experiencing, I thought it would be worthwhile and go back to Aristotle. Before we can think at all about how to be better friends, we may want to think about what friendship is.

It is in Book 8 of the Nicomachean Ethics that Aristotle explicitly turns to friendship, noting early on:

Without friends, no one would choose to live, even if he possessed all other goods; and indeed those who are wealthy or have acquired political offices and power seem to be in need of friends most of all.

Friendship, Aristotle goes on to say, saves us from error, ensures that we will be cared for as we age, protects us from the worst of poverty and misfortune. Friendship even provides us with an opportunity for self-knowledge, fulfilling the Delphic maxim to know thyself. Through our relationship to another, particularly through our relationship with another virtuous person, we can see ourselves more clearly.

Aristotle makes a distinction between three sorts of friends, at least between equals.1

First, we have friends of utility. A friend of utility is a friend that one has because they provide something for you: social connections, material wealth, opportunities for career advancement. These friendships are brittle and often asymmetric. One friend typically provides more value than the other, at some point it becomes pointless for one friend to continue the friendship. When circumstances change, the friendship rarely adapts. Instead, it ends.

Second, friends of pleasure. These are friends who provide you with pleasure, broadly construed. Aristotle believes that these are especially prevalent among the young, who tend to pursue pleasure more zealously than the old. Like friendships of utility, friendships of pleasure are unstable. What provides pleasure for me now may not later — beauty fades, my interests shift, and the craving for more intense and concentrated pleasures grow.

Third, we have friends of virtue. Aristotle also calls these ‘complete’ friendships. These are friendships in the fullest sense of the term. Friends, in this scenario, are perfectly alike in virtue. This kind of friendship is highly restricted. Those who are not sufficiently virtuous, whom Aristotle calls ‘base’, are unable to form these kinds of friendship. Only the virtuous can have full and complete friendships, friendships which go beyond utility and pleasure.

Note that last clause: go beyond. A virtuous friendship will almost certainly bring the friends pleasure of some sort, and very often there will be opportunities for utility, but that is not the core of the friendship. A virtuous friendship may include pleasure and utility, but it consists in something greater.

Insofar as Aristotle emphasizes the necessity of friendship in the good life, I take him to have a better theory than the Stoics. The Stoics do not dismiss or denigrate friendship — I can recall passages of Musonius Rufus on the matter, and Seneca valued friendship enough to bother with letter-writing. But the core, radical Stoic claim is that virtue alone is sufficient for happiness, and that all people are capable of acting virtuous at all times. Happiness is a choice for the Stoics. Aristotle and his Peripatetics allow that the world may not cooperate and may frustrate one’s virtue and thus happiness; the case of friendship strengthens their point.

The philosopher and essayist Michael Oakeshott is clearly drawing on Aristotle in his essay ‘On being conservative,’ where he gives a brief treatment of what he takes to be conservative relations. Friendship is chief among them. Oakeshott writes:

But there are relationships of another kind in which no result is sought and which are engaged in for their own sake and enjoyed for what they are and not what they provide. This is so of friendship. Here, attachment springs from an intimation of familiarity and subsists in a mutual sharing of personalities.

Oakeshott, I think it is clear, is echoing Aristotle’s thoughts on the matter. ‘Friendship’ in his essay is the complete friendship of Aristotle. It is a delicacy: rare, to be savored, and always to be enjoyed together.

Oakeshott contrasts this relationship with the relationship you might have toward your butcher. Your butcher provides you with a service, and you choose to frequent your butcher because he does the job well. The meat is of quality, well-prepared, and offered at a price you find agreeable. If your butcher became unable to provide you with meat, you would find another butcher. But friendships are not like this. ‘To discard friends because they do not behave as we expected and refuse to be educated to our requirements,’ Oakeshott tells us, ‘is the conduct of a man who has altogether mistaken the character of friendship.’

Nearly all of our relations are in some sense economic. They involve the mutual exchange of goods, services, money, etc. They are transactional. Even more base forms of friendship, grounded in utility or pleasure, are transactional. The complete friendship goes beyond this. The person becomes valued in themselves. The relationship itself becomes a thing worth maintaining.

And that, I think, is one of the profound losses of the modern crisis of friendship. As we become less likely to have friends, we become increasingly likely to instrumentalize human relationships. They are valuable because they offer something to us — not because they simply are a thing worth valuing.

Aristotle also has a theory of friendship based on superiority, found in Book 8, Chapter 7. These are friendships which involve one friend have greater status than the other: fathers over sons, teachers over students, and so on. Samwise and Frodo have a friendship like this, though one that matures based on the virtues and heroism displayed by both.