There is no oracle

Being Socratic in the age of the Bullshit Machines

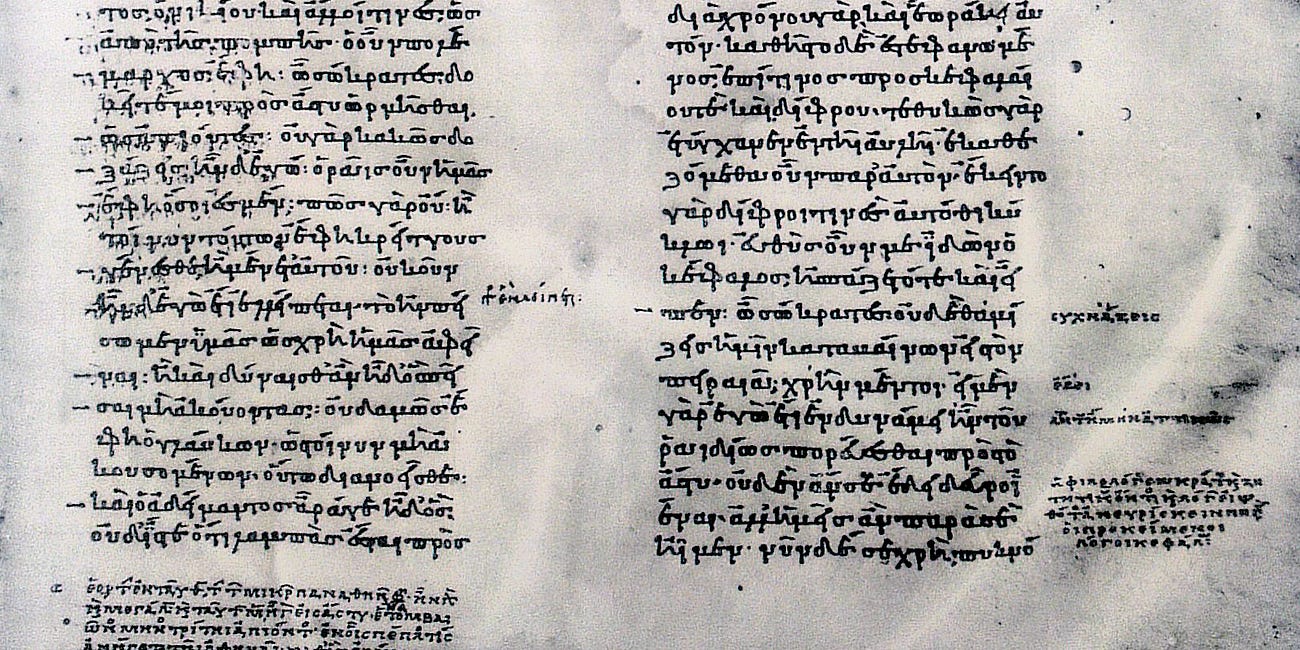

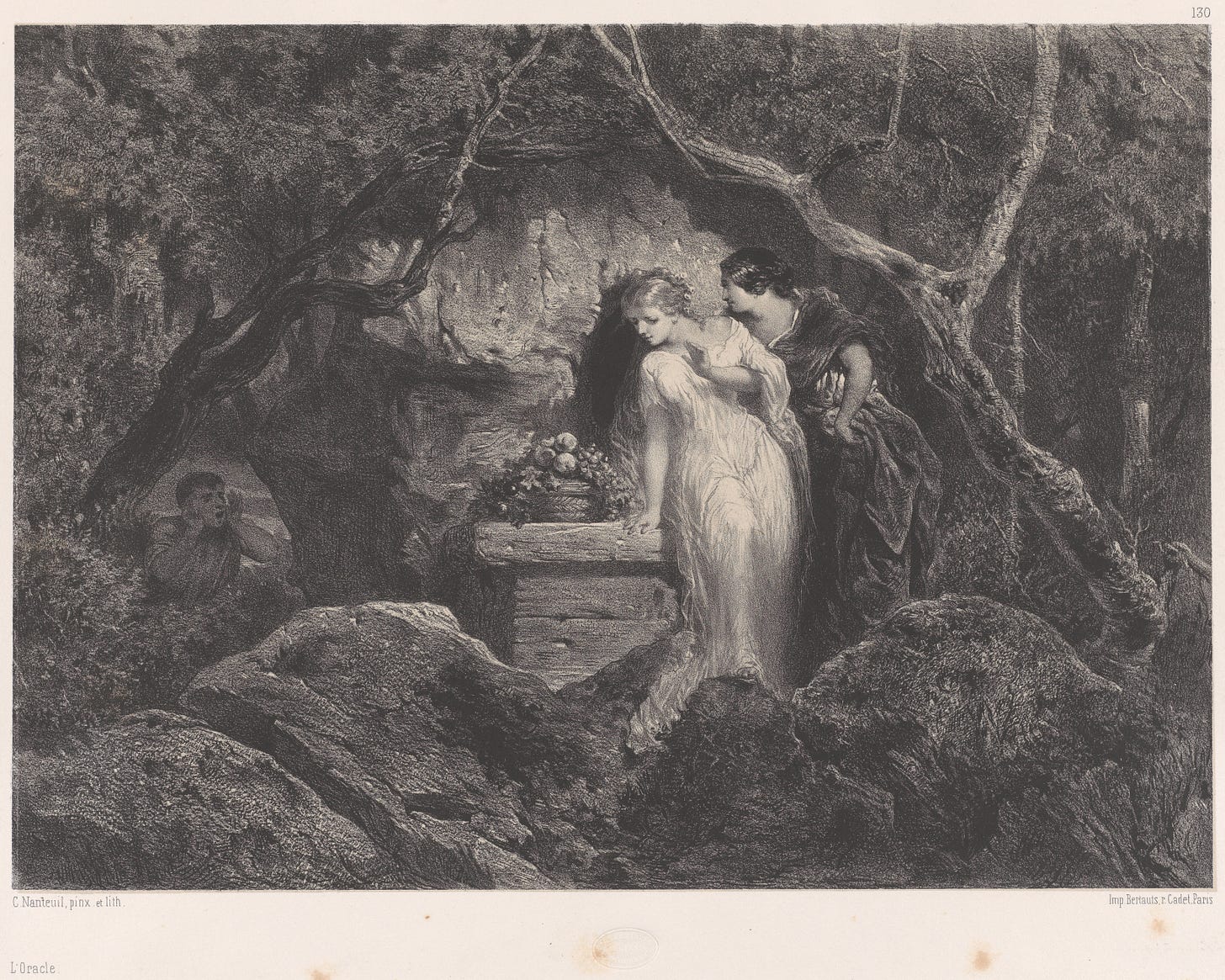

The legend of Socrates begins with a visit to the Delphic oracle, the Pythian priestess believed to speak on behalf of Apollo. Chaerephon, a friend to Socrates, visits the oracle and asks if anyone is wiser than Socrates. She tells him no; Socrates is the wisest.

For some, this would be an affirming message. A divine messenger, an oracle, has told you that you are the wisest man (perhaps in Athens, perhaps in the entire world). Socrates doesn’t take it this way, however. He’s troubled. At his trial, Socrates says:

When I heard of this reply I asked myself: "Whatever does the god mean? What is his riddle? I am very conscious that I am not wise at all; what then does he mean by saying that I am the wisest? For surely he does not lie; it is not legitimate for him to do so." For a long time I was at a loss as to his meaning; then I very reluctantly turned to some such investigation as this: I went to one of those reputed wise, thinking that there, if anywhere, I could refute the oracle and say to it: "This man is wiser than I, but you said I was."

The rest of the story is familiar to anyone who has read Plato’s dialogues. Socrates develops a reputation for trouble-making, as he pokes and prods at the allegedly wise. He regularly confronts men who think themselves wise, often exposing their inconsistencies.

By the way, if you want to read some Platonic dialogues, the Republic is a good place to start. We’re reading it together starting at the end of March.

Getting Ready for Plato's Republic

At the end of this month, we’re going to read Plato’s Republic together. The Republic is traditionally divided into ten books, which gives us a helpful division for working through the text together.

Socrates’ story begins with a refusal to defer to an oracle. He refuses to take the easy way out, to stop asking the big questions. In more modern terms: he owns it. He says ‘I will continue to question, even the words of the gods themselves.’

Read this way, there might be something to the charge of impiety. Socrates is refusing to take Apollo, or at least his mouthpiece, at his word. I could see how a zealous Greek could believe that this was impious.

I also believe that it was the right thing to do.

I’ve noticed a new online trend. It’s a troubling one. When two people get into a debate online, very quickly one of the interlocutors will refer to AI to get a quick answer and settle the dispute. ‘Well, the AI says…,’ they’ll say. If you refuse to accept the answer, then you’re being, well, rather impious. The oracle has spoken; you should believe it.

Of course, this is a horrible strategy if you are at all interested in the truth. Generative AI is impressive and helpful in some contexts, but when it comes to fact-checking, these systems are Bullshit Machines.1 They generate things that sound good and meaningful, but they have little to no attachment to the world.

Sometimes, relying on generative systems for fact-checking has hilarious, maybe disastrous, consequences. During the dust-up about Joe Biden’s pardon of his son Hunter (an egregious example of nepotism, giving a relative a blanket ten-year pardon), a CNN commentator sought to defend him by appealing to historical precedents. She posted a screenshot from a conversation with ChatGPT; that conversation listed several examples of presidents pardoning their close relations. The problem? It was bullshit. The AI made it up, and the commentator couldn’t be bothered to double-check anything.

Esquire made a similar mistake, claiming George H.W. Bush pardoned his son Neil. The problem? Neil Bush was not given a pardon by his father. That article is now retracted, with no evidence of what the mistake was or how Esquire’s editorial system allowed such a tremendous error.

In the case of CNN’s commentator, we know she used ChatGPT. As she put it when challenged: ‘Take it up with ChatGPT.’ Esquire never confirmed this was an instance of using AI, but it looks suspiciously like it. A complete historical fabrication that seems to fit all too perfectly into the writer’s narrative? That’s just the job for a Bullshit Machine.

Now, this cognitive offloading (without regard for bullshit) is everywhere. On X, users regularly ask ‘Grok, is this true?’ as a means of fact-checking their enemies. Pay no mind to the fact that Grok is just as unreliable as all of these systems. At least it sounds good.

The technology is new, more powerful than ever, and growing in influence, but the problem is nothing new. We have long wanted someone or something to tell us all the answers. We consult oracles of all kinds: Delphic priestesses, chicken bones, tea leaves, Tarot cards, internet encyclopedias, and fast-talking gurus. For millennia, we have cried out desperately for someone to relieve us of the responsibility of inquiry.

But like Socrates, we should refuse this temptation. Each of us should say, ‘I am a human being, in possession of rational faculties, and I will use them to their fullest extent.’ And we should say no to the Bullshit Machines which tell us that they can handle that for us. They can’t, and we shouldn’t want them to, anyway.

See ‘ChatGPT is Bullshit’ by Hicks, Humphries, and Slater

This is exactly what my Socratic machine was telling me.

As much as I enjoy and have gained from Plato's Republic, I would not necessarily recommend it as the first of Plato's dialogues that one should read. Republic is significantly longer, more sophisticated, and generally more intimidating than most of Plato's other dialogues.

On the other hand, if I were going to read only one of Plato's dialogues, it would be Republic. Indeed, if I were going to read only one work of philosophy ever, Republic would be one of the main contenders.