Exercising Self-Restraint | Nicomachean Ethics, Book VII

Today, we continue our read-along of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. If you’re just now joining and want to catch up, here is the schedule we are following (with links to previous posts):

July 8: Book I

July 15: Book II

July 22: Book III

July 29: Book IV

August 5: Book V

August 12: Book VI

August 19: Book VII

August 26: Book VIII

September 2: Book IX

September 9: Book X

September 16: Retrospective

This read-along of Nicomachean Ethics is free. But if you want to support my work – which really means helping me support my family – and you want access to the monthly Zoom calls, become a paying subscriber. For the rest of August, a yearly subscription to Walking Away is 20% off. To subscribe and support my work on Substack and YouTube, just go to this link.

We’ll have our next Zoom call on September 15 at 8 PM Eastern. The third Sunday of the month seems to be working well, and I think we might make that the designated evening for a call going forward.

Aristotle (and the Peripatetics, those who would go on to continue and develop his philosophy) are note hedonists. This sets them apart from the Epicureans, who believed that pleasure was what made life good. (NB: this is very different than what we mean by ‘hedonism’ now. The Epicureans lived very boring lives by modern hedonistic standards.) Clearly, Aristotle favors happiness – understood in terms of virtue – over mere pleasure.

Yet, Aristotle did believe that pain was bad and pleasure was good (VII.14, 1153b). This also sets him apart from the Stoics. Famously, the Stoics deemed pleasure a preferred indifferent — it was something to be preferred over pain, but it contributed nothing to a good life. Aristotle on the other hand understood plesasure as a potential good in one’s life.

What was important, however, was the recognition that some pleasures are bad (or base). The pleasures of the glutton are not worth having, I would say. And some pains are worth enduring for the sake of something noble — one example I would think of is the man who endures torture to save his brothers in arms. Aristotle has a moderate, nuanced view of pleasure in relation to the good life.

The happy life will be pleasant, Aristotle says, because it is a complete life, and thus it cannot be lacking. But a happy life will have its share of pains as well; that is simply the state of the world.

I’ve inverted the discussion of Book VII a bit, starting with the late discussion of pleasure and pain that ends the book. This is for a good reason. Book VII begins with an odd line – we must begin again, we are told – and it turns out that our discussion of the good life has been too one-dimensional in its focus on virtue.

We need to broaden our discussion and meditate on self-restraint and brutishness. Like virtue and vice, these pertain to character — and virtue ethics emphasizes the development of one’s character.

But when you start reading a book like this, and suddenly you are told you must begin again, it can be exasperating. So I wanted to discuss pleasure and pain very briefly to see why this matters. All of us have struggled with the role of pleasure in our lives. Many times we have pursued certain pleasures and regretted it — for instance, I cannot let myself play video games or even online chess without strict limits, as I struggle to regulate myself. Or if you drink too much, you regret it later. If you’re going to live a good life, you need to have an appropriate relationship to pleasure.

This means you will need to exercise self-restraint.

It is easy to over-intellectualize your view of moral action. Socrates, Aristotle says, believed that if one had scientific knowledge, one would not act wrongly; knowledge of this kind is guaranteed to guide you properly. This is not the Aristotelian view as I understand it. “This argument [Socrates’ argument]…is in contention with the phenomena that come plainly to sight,” Aristotle writes in chapter 2. If one lacks self-restraint, one can be overpowered by passion. The passions make you, the agent, passive. They act, it seems, not you.

So we need to develop self-restraint so that we can abide by our calculations. Developing prudence allows us to deliberate and arrive at the best course of action; self-restraint allows us to follow through with this plan. What could cause you to not follow through? An incorrectly calibrated sense of pleasure and pain, primarily. If you prefer things which are base, or do not properly value those things which are noble, you will not be steadfast.

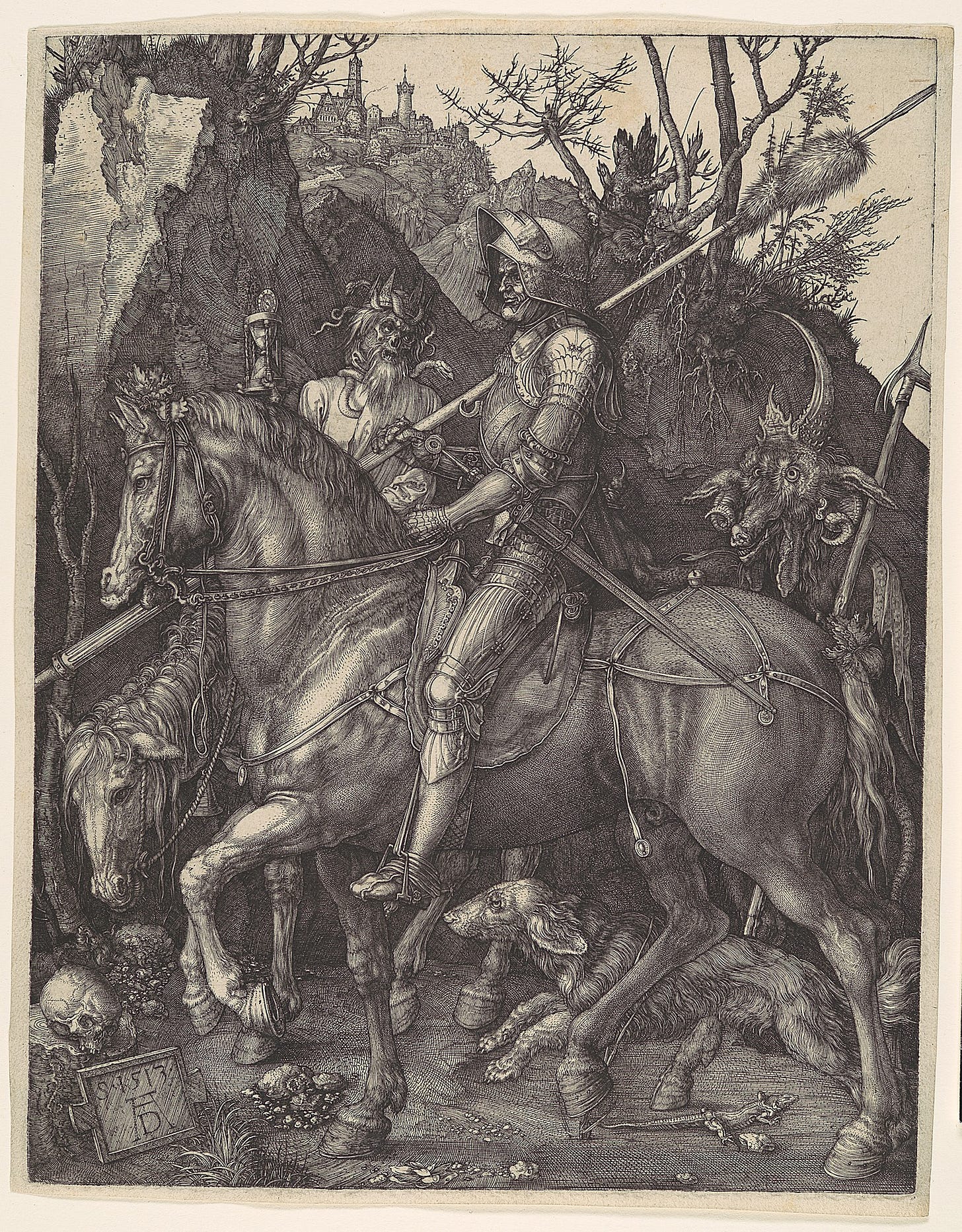

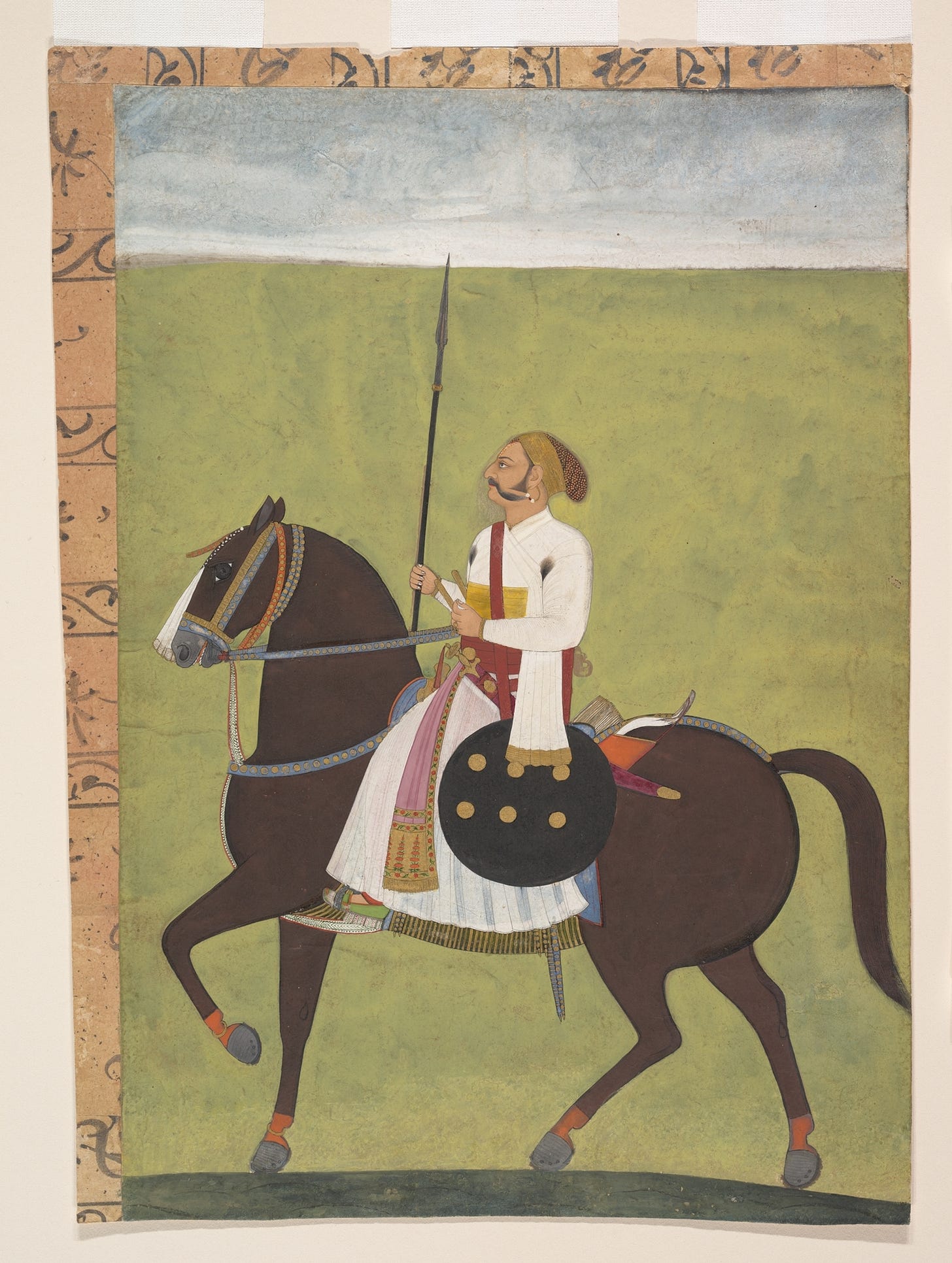

It is helpful to now look back at some of the earlier vices we discussed: courage and moderation. Someone may be able to prudently determine the best way to approach, say, food, or to identify the principles that govern a soldier on the battlefield. But when you then see that pizza and wine on the kitchen table, or you see the enemies charging with their spears and shields, will they act rightly? If not, then they do not have self-restraint.

Eventually, acting without self-restraint over and over forms your character. You will lose the ability to determine the right course of action, I believe, because your ability is really a habit, and habits must be maintained. So a lack of self-restraint is ultimately destructive for virtue and conducive to vice.

Before we end today’s discussion, I want to highlight a comment from my last post about Aristotle. It is helpful for anyone who has fallen behind on the read-along.

Cindy wrote:

As I am more than halfway through Book 8, I would encourage anyone who has fallen behind to persevere. Book 8 feels like a reward for all the work we’ve done.

This is exactly correct. Book VIII is the best book of Nicomachean Ethics, in my opinion. I am so looking forward to reading it with you. Even if you have fallen behind, just jump in to Book VIII and savor it.

I started thinking more deeply about prudence after our discussion on Sunday. Can prudence be taken too far, thus keeping us from acting even though it might be dangerous? If I see two people fighting, do I do the prudent thing and protect myself first? I could call the police and wait to see what happens, thus physically protecting myself. But what if one of the people is hurt and I can stop them from being further injured. Some people would jump into the fray without thinking of self-preservation. Does that action make them a better person?

Thank you for your hard work, Jared. Your comments are very helpful, especially for the last couple of books. I get lost in all the divisions that are made and have trouble finding my footing. Your articles have helped me grasp the main idea of each book and reflect a lot more on what I read. This book has earned a re-read for me in the future, that's for sure!