Today we begin our read-along of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. This is my favorite science fiction novel, and certainly one of the most impactful books on my own life, and I’m looking forward to revisiting this world with all of you.

The schedule for the read-along can be found here.

February 10: Introduction to Le Guin’s life and work

February 17: Chapters 1-3

February 24: Chapters 4-6

March 2: Members-Only Zoom Call, 8PM Eastern

March 3: Chapters 7-9

March 10: Chapters 10-13

March 13: Members-Only Zoom Call, 3PM Eastern

On the appointed dates, I’ll send out my thoughts on the reading. Then, everyone can discuss the reading in the comments. This read-along, like all of them, is what we make of it! By bring your thoughts to the comments, you’re hopefully making the experience better for everyone.

All of those posts are free — anyone can join. But twice during this read-along (March 2 and March 13), I’ll be hosting members-only Zoom calls to discuss the book with paying subscribers. If you want to join those calls, just click the button below.

(And since people always ask: I send the links out about an hour before the calls, both via Substack Chat and via a separate paid-only post.)

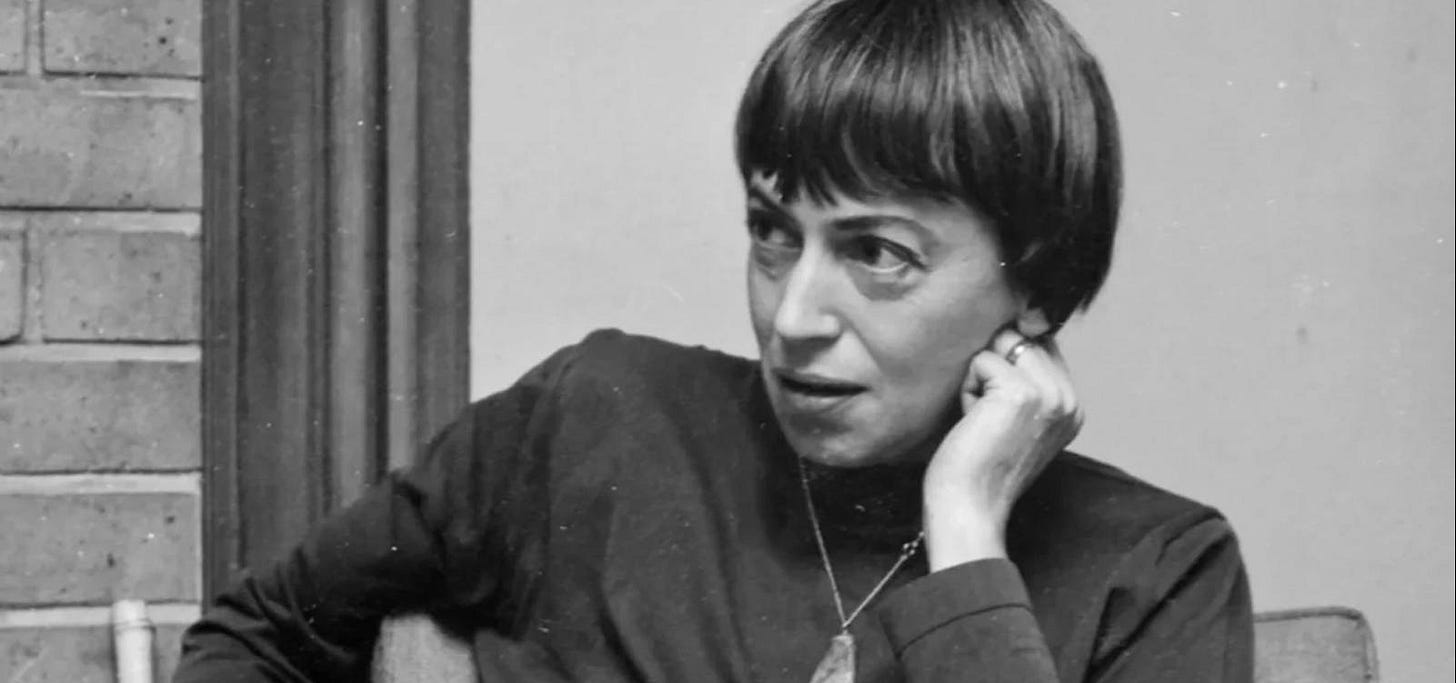

I promised an introduction to Le Guin’s life and work today. So, let’s begin.

Ursula K. Le Guin was born to Alfred and Theodora Kroeber in 1929. Her father was a renowned anthropologist, and he served as the director of the Museum of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley for many years. Her parents had a wide and varied social circle, allowing a young Ursula to be exposed to a rather extraordinary range of people.

When it comes to genre fiction, Le Guin had a complicated relationship. Le Guin is clearly an author of science fiction and fantasy — yet, throughout her career she resisted these labels. Instead of terms like ‘literary fiction’, so often used to indicate that a work is real literature, she preferred the label mimetic fiction for work that hewed closer to reality. Yet, it is in science fiction and fantasy (or as I like to call it, speculative fiction) that she was the most honored. She was the first woman to win both the Hugo and the Nebula for best novel, given to her for the 1969 The Left Hand of Darkness. (I believe she was only the second woman to win the Hugo for best novel, with Joanna Russ winning several years prior.) In total, she won eight Hugos, six Nebulas, twenty-five Locus Awards.

But Le Guin was not limited to speculative fiction, and her influence is felt widely. David Mitchell, a favorite of mine, clearly is influenced by Le Guin; Michael Chabon called her the greatest American writer of her generation.

Awards are cheap, but printing books costs money. The Library of America has printed multiple volumes of Le Guin’s work; she is, I believe, one of their most-published authors. (I would one day like to see an LoA Earthsea, but who knows if or when that could happen.)

Le Guin is best known for her earliest work. She began her career in 1966 with the publication of Rocannon’s World, released to near-total silence. But in 1968 she published A Wizard of Earthsea followed quickly by 1969’s The Left Hand of Darkness and 1971’s The Lathe of Heaven. In 1974 she published what I think is her masterpiece: The Dispossessed. Yet, we shouldn’t overlook the fact that she continued to published until her death in 2018, including many more Earthsea novels.

Le Guin was not afraid to bring philosophical ideas to her novels, and it is commonly (and fairly) said that Le Guin was inspired by three schools of thought: Taoism, Jungian psychology, and non-violent anarchism. These influences tend to wax and wane throughout her career, and it is too reductive to think all she did was fictionalize these ideas. But you do see these ideas, and especially the anarchism, in The Dispossessed. It is an attempt to write a utopia of sorts…but Le Guin cannot let herself do anything in a straightforward way, and so The Dispossessed is an ambiguous utopia. Those ambiguities are what make it such a compelling read.

A common question – I’ve been asked several times in the past few weeks – concerns The Dispossessed’s relationship to the other novels that comprise the Hainish Cycle. There is a short answer and a long answer.

Short answer: aside from some references, a vaguely (but perhaps inconsistently) shared setting, there is no important connection. Le Guin merely wrote against a common backdrop in her imaginative fiction.

Here’s how Le Guin describes it:

People write me nice letters asking what order they ought to read my science fiction books in — the ones that are called the Hainish or Ekumen cycle or saga or something. The thing is, they aren't a cycle or a saga. They do not form a coherent history. There are some clear connections among them, yes, but also some extremely murky ones. And some great discontinuities (like, what happened to "mindspeech" after Left Hand of Darkness? Who knows? Ask God, and she may tell you she didn't believe in it any more.)

The long answer: in the background of the Hainish novels (which Le Guin also calls the ‘Ekumen cycle’ in the above quote), there is a shared history of humanity across many planets. Humans did not originate or evolve on Earth (called Terra); instead, they are the product of an interstellar anthropology experiment. The Hain experimented on humans and planted them on other planets. Thus, the hermaphroditic species in The Left Hand of Darkness. Humans across many planets are forming a coalition, called the Ekumen; this provides a nice way for Le Guin to write first contact stories.

Even with this history and connection, there is no need to read any of the other novels to understand The Dispossessed. One of the great sins of genre fiction, I have come to believe, is writing a novel that cannot stand on its own; we’ve become so used to trilogies or longer series that we’ve seemingly forgotten that every novel should tell a complete, comprehensible story. At least in the Hainish Cycle, Le Guin did not commit this sin.1

She did write some series. Earthsea clearly needs to be read in a particular order to see the evolution of the characters. Yet, every Earthsea novel could theoretically stand on its own. This stands in stark contrast to many big fantasy series that demand a reader commit to 7 or 10 novels to get a full story.

Just wanted to say thank you for the nudge. Having read the Earthsea books as teenage I’ve not explored her works any deeper even though this has novel been accessible from the wife’s bookshelf for decades.

Thank you for this introduction.