"Where, then, is Truth?" | The Dispossessed, Chapters 1-3

In the hill one happens to be sitting on

The schedule for the read-along can be found here.

February 10: Introduction to Le Guin’s life and work

February 17: Chapters 1-3

February 24: Chapters 4-6

March 2: Members-Only Zoom Call, 8PM Eastern

March 3: Chapters 7-9

March 10: Chapters 10-13

March 13: Members-Only Zoom Call, 3PM Eastern

All of those posts are free — anyone can join. But twice during this read-along (March 2 and March 13), I’ll be hosting members-only Zoom calls to discuss the book with paying subscribers. If you want to join those calls, just click the button below.

(And since people always ask: I send the links out about an hour before the calls, both via Substack Chat and via a separate paid-only post.)

We’ve now read three chapters of The Dispossessed, Le Guin’s attempt – of a sort – to write a utopian novel about non-violent anarchism. We can discuss for the rest of the read-along how successful this is, and whether the ambiguity of her utopia impacts our view of the various philosophies, but for now, we should get to know the characters.

The protagonist is Shevek, a physicist from the world of Anarres, the habitable moon of the larger, lusher world of Urras. At the beginning of the novel, Shevek is voyaging to Urras on the Mindful, a freighter that brings goods between the worlds. And clearly, some are not happy about this.

“Some of them had come there to kill a traitor. Others had come to prevent him from leaving, or to yell insults at him, or just to look at him…” Le Guin writes. One of the would-be killers is successful, but the wrong man is killed. A member of the Defense syndic is struck by a rock and killed.1

Anarres is a world without walls — except at the space port. Le Guin highlights the dual nature of this wall on the very first page:

Like all walls it was ambiguous, two-faced. What was inside it and what was outside it depended upon which side of it you were on.

The people of Anarres might view this as a wall that keeps the Urrasti out, keeping the Port of Anarres as a peculiar and confined spot where the propertarians can be on their planet. “It enclosed the universe, leaving Anarres outside, free.” But from the other side, it is the Anarresti, the Odonians, that are within the walls; the whole planet is a prison camp, “cut off from other worlds and other men, in quarantine.”

This point about walls is thematic, and you’ll see Le Guin alternating between dual perspectives throughout the novel. And this will be (as we’ve already seen) interwoven with Shevek’s idea of physics. (This is something I think we should explore a little bit later — Le Guin is planting seeds, but I’ll wait for them to sprout.)

That’s another fun part of the novel — its main character is a philosopher-physicist who some aliens suspect is merely a mystic.

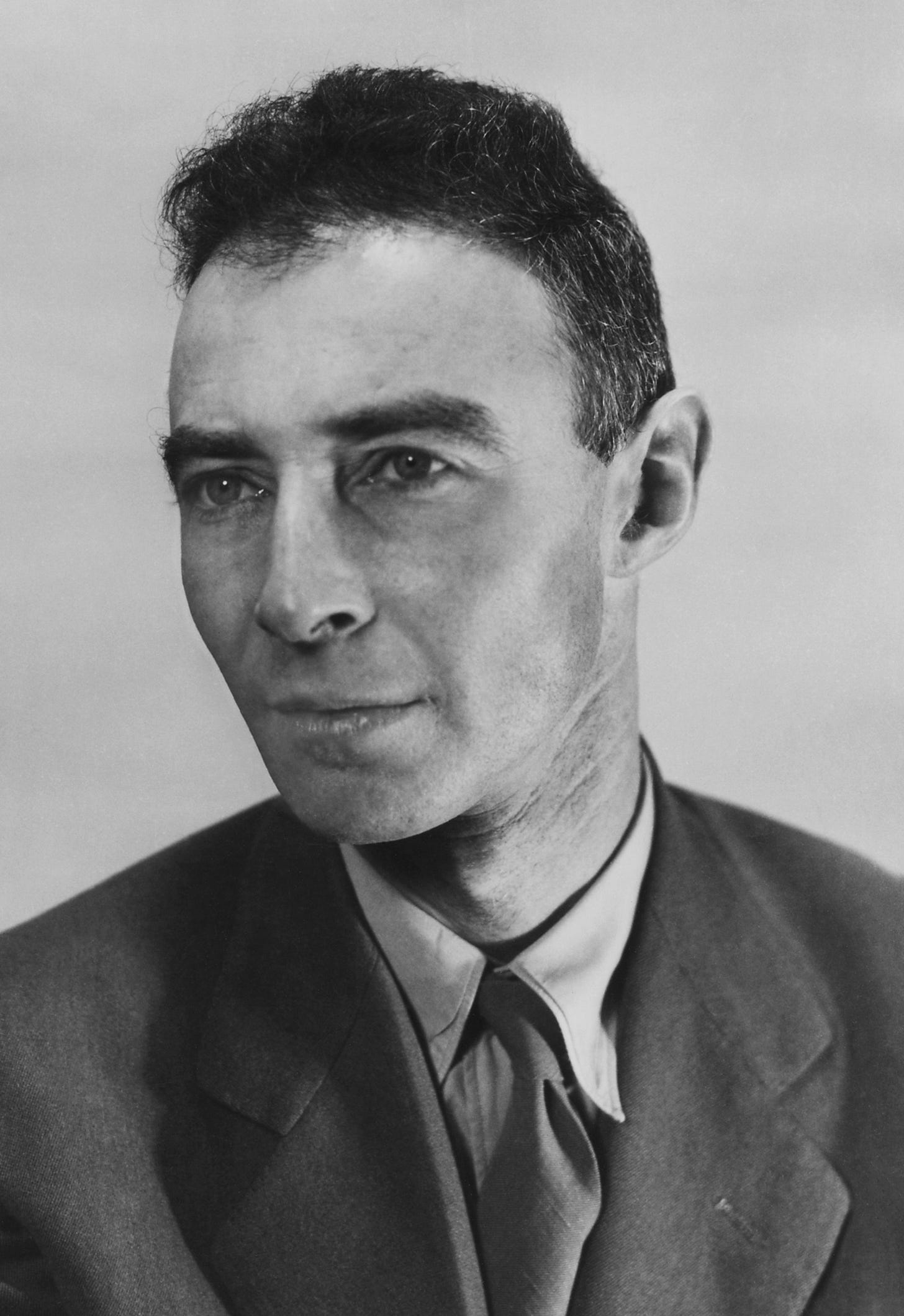

The apparent inspiration for Le Guin is J. Robert Oppenheimer, a man Le Guin met in her childhood through her parents. Oppenheimer is a man for him the description great and terrible is fitting. He is also, as was well illustrated in the recent Christopher Nolan biopic, a man torn between worlds.

But as a first-time reader of The Dispossessed, you likely are not thinking about physics or the real-world inspiration for Shevek. You’re thinking about the contrast between Urras and Anarres. You’re thinking about anarchism.

The people of Anarres call themselves Odonians, followers of Laia Asieo Odo. Odo apparently was a revolutionary writer who spent many years in prison; she is buried on Urras, the Trans-Sua district of A-Io. The pecularities of Odonianism – the modes, the Analogy, and so on – will be made more apparent throughout the novel. After Odo’s death, settlers were brought from Urras to Anarres to live out Odonian principles, to engage in permanent revolution.

But in broad outline, the people of Anarres are anarchists. They believe in the principle of mutual aid. Shevek, like a good Anarresti, moves by his own initiative — the only one he acknowledges.

How this anarchism impacts their lives is often reflected in language, for instances the lack of a idiomatic possessive in Pravic, the constructed language of Anarres. You also see it more subtly when Shevek interacts with the Urrasti:

“I come,” he said carefully, “as a syndic of the Syndicate of Initiative, the group that talks with Urras on the radio these last two years. But I am not, you know, an ambassador from any authority, any institution. I hope you did not ask me as that.”

”No,” Oiie said. “We asked you — Shevek the physicist. With the approval of our government and the Council of World Governments, of course. But you are here as the private guest of Ieu Eun University.”

When Oiie, one of the physicists welcoming Shevek, speaks, he draws on authority — but not his own. Three institutions validate the invitation: the A-Io government, a broader council, and a university. Shevek, again, comes by his own initiative.

As Shevek enters into Urras, he encounters many unfamiliar things. A servant acts deferentially to him; women are segregated and barred from most professions; everyone is clean-shaven (hair is a common image in The Dispossessed, and the greatest contrast is with Shevek’s mane and beard and the hairless and oiled women of A-Io). He also experiences a world of abundance and luxury. By the end of Chapter 3, he has fallen in love.

Yet he recognizes that he is not of A-Io or Urras; his people separated themselves and made Anarres their home. Now, he has separated himself from Anarres. He has taken a journey, and he is alone.

Syndicates, sometimes called syndics, are organizations of people around a common purpose. Shevek mentions at several points being a member of the Syndicate of Initiative.

I’m trying to understand the overarching philosophy that Shevek starts to really develop in Chapter 2, starting with the reference to how you can never step into the same river twice. If I’m understanding Shevek’s argument, it’s that all individual things change, but the relationship between them remains (or can remain) constant. He might change, and the waters of the river certainly change, but the way he relates to the river does not. “Home is a place you’ve never been” means that home is the relationship between you and another person, place, or thing. I think there’s also something here connecting to his dream where his parents showed him the “primal number” that represents both unity and plurality. You need distinct individuals in order to form a relationship (or to make up a collective), and neither have meaning without the other.

At the end of Chapter 2, Shevek argues that “brotherhood is shared suffering,” and I think what he means by this is that true brotherhood is recognizing that when one individual suffers, all suffer, because all individuals are ultimately one. Shared suffering doesn’t mean hurting yourself in solidarity when you see someone else hurting. It means seeing that the inescapable, shared suffering of existence is proof of our ultimate unity or oneness, which is experienced as relationship.

So, if relationship between individuals itself is prime (as opposed to specific arrangements of individuals in hierarchical or anarchist societies), then it’s immoral to maintain a divide between Urras and Anarres, and to villainize other people as both worlds have done to one another. Shevek is motivated to seek universal connection, relationship, or brotherhood, because prioritizing the material wellbeing of only individuals (Anarres) or of the collective (Urras) neglects the fundamental primacy of connection and relationship at all levels of and across societies.

"Initiative" as a concept (and its relationship with desire and necessity) is what is sticking out for me the most on this read. I can't count how many times I've read this book, but in previous readings the political formations of the two worlds (obviously) and the romance (somewhat less obviously) are what really stood out for me.

I initially thought of initiative as a kind of authentic desire, constrained by necessity, but as I read further I began to think of initiative as more of a natural function of a "healthy" human society and the individuals those societies produce — initiative as something more akin to the way a bee gathers honey and builds hives, albeit with a conceptual element.